Szlachta

The szlachta (Polish: [ˈʂlaxta] ⓘ; Lithuanian: šlėkta; English: Nobility) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and, as a social class, dominated those states[1] by exercising political rights and power.

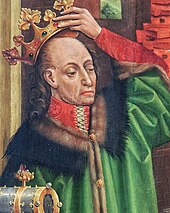

[13] The szlachta secured substantial and increasing political power and rights throughout its history, beginning with the reign of King Casimir III the Great between 1333 and 1370 in the Kingdom of Poland[10]: 211 until the decline and end of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the late 18th century.

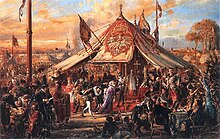

Apart from providing officers for the army, its chief civic obligations included electing the monarch and filling honorary and advisory roles at court that would later evolve into the upper legislative chamber, the Senate.

[14] In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, the existing Lithuanian and Ruthenian nobilities formally joined the szlachta.

In modern German Geschlecht – which originally came from the Proto-Germanic *slagiz, "blow", "strike", and shares the Anglo-Saxon root for "slaughter", or the verb "to slug" – means "breeding" or "gender".

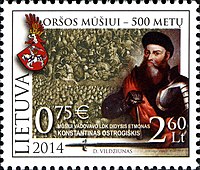

The first theory involved a presumed descent from the ancient Iranian tribe known as Sarmatians, who in the 2nd century AD, occupied lands in Eastern Europe, and the Middle East.

[10]: 207 [10]: 208 Another theory describes its derivation from a non-Slavic warrior class,[43]: 42, 64–66 forming a distinct element known as the Lechici/Lekhi (Lechitów)[44][17]: 482 within the ancient Polonic tribal groupings (Indo-European caste systems).

[21][26] In the year 1244, Bolesław, Duke of Masovia, identified members of the knights' clan as members of a genealogia: "I received my good servitors [Raciborz and Albert] from the land of [Great] Poland, and from the clan [genealogia] called Jelito, with my well-disposed knowledge [i.e., consent and encouragement] and the cry [vocitatio], [that is], the godło, [by the name of] Nagody, and I established them in the said land of mine, Masovia, [on the military tenure described elsewhere in the charter]."

Members of the szlachta had the personal obligation to defend the country (pospolite ruszenie), thereby becoming within the kingdom a military caste[21][26] and aristocracy[3] with political power and extensive rights secured.

[66] The tribes were ruled by clans (ród) consisting of people related by blood or marriage and theoretically descending from a common ancestor,[61] giving the ród/clan a highly developed sense of solidarity.

Major effects on the lesser Lithuanian nobility occurred after various sanctions were imposed by the Russian Empire, such as removing Lithuania from the names of the Gubernyas shortly after the November Uprising.

[citation needed] The rights of Orthodox nobles were nominally equal to those enjoyed by the Polish and Lithuanian nobility, but they were put under cultural pressure to convert to Catholicism.

Agnomen (nickname, Polish przydomek): Żądło (prior to the 17th century, was a cognomen[77]) Bartosz Paprocki gives an example of the Rościszewski family taking different surnames from the names of various patrimonies or estates they owned.

[citation needed] When mixed marriages developed after the partitions, that is between commoners and members of the nobility, as a courtesy, children could claim a coat of arms from their distaff side, but this was only tolerated and could not be passed on to the next generation.

This can most readily be explained in terms of the ongoing decline and eventual collapse of the Commonwealth and the resulting need for soldiers and other military leaders (see: Partitions of Poland, King Stanisław August Poniatowski).

Henceforth, district offices were also reserved exclusively for local nobility, as the Privilege of Koszyce forbade the king to grant official posts and major Polish castles to foreign knights.

King Władysław's quid pro quo for the easement was the nobles' guarantee that the throne would be inherited by one of his sons, who would be bound to honour the privileges granted earlier to the nobility.

The latter document was a virtual Polish constitution and contained the basic laws of the Commonwealth: In 1578 king, Stefan Batory, created the Crown Tribunal to reduce the enormous pressure on the Royal Court.

This gave rise in the 16th century, to a self-policing trend by the szlachta, known as the ruch egzekucji praw — movement for the enforcement of the law – against usurping Magnates to force them to return leased lands back to their rightful owner, the monarch.

[citation needed] One of the most important victories of the Magnates was the late 16th century right to create Ordynacjas, similar to Fee tails under English law, which ensured that a family which gained landed wealth could more easily preserve it.

[67] The notion of the szlachta's accrued sovereignty ended in 1795 with the final Partitions of Poland, and until 1918 their legal status was dependent on the policies of the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia or the Habsburg monarchy.

Despite preoccupations with warring, politics and status, the szlachta in Poland, as did people from all social classes, played its part in contributing in fields ranging from literature, art and architecture, philosophy, education, agriculture and the many branches of science, to technology and industry.

[106] In the 18th century, after several false starts, international Freemasonry, wolnomularstwo, from western lodges, became established among the higher échelons of the szlachta, and in spite of membership of some clergy, it was intermittently but strongly opposed by the Catholic Church.

During the Age of Enlightenment, King Stanislaw August Poniatowski emulated the French Salons by holding his famed Thursday Lunches for intellectuals and artists, drawn chiefly from the szlachta.

With the introduction of rulers and rules, big game, generically zwierzyna: Aurochs, bison, deer and boar became the preserve of kings and princes on penalty of poachers' death.

The exception were the Prokopenko-Chopovsky branch of the family who were received into the Russian nobility in 1858,[136]However the era of sovereign rule by the szlachta ended earlier than in other countries, excluding France, in 1795 (see Partitions of Poland).

According to two English journalists Richard Holt Hutton and Walter Bagehot writing on the subject in 1864, The condition of the country at the present day shows that the population consisted of two different peoples, between whom there was an impassable barrier.

[17]: 483–484 and ... the Statute of 1633 completed the slavery of the other classes, by proclaiming the principle that 'the air enslaves the man,' in virtue of which every peasant who had lived for a year upon the estate of a noble was held to be his property.

[143] The szlachta's prevalent ideology, especially in the 17th and 18th centuries, was manifested in its adoption of "Sarmatism", a word derived from the legend that its origins reached back to the ancient tribe of an Iranic people, the Sarmatians.

Sarmatism served to integrate a nobility of disparate provenance, as it sought to create a sense of national unity and pride in the szlachta's "Golden Liberty" złota wolność.