Ukrainian nobility of Galicia

The shlyakhta (Ukrainian: шля́хта, Polish: szlachta) were a noble class of Ruthenians in what is now Western Ukraine that enjoyed certain legal and social privileges.

According to mainstream Ukrainian historiography, the western Ukrainian nobility developed out of a mixture of three groups of people: poor Rus' boyars (East Slavic aristocrats from the medieval era), descendants of princely retainers or druzhina (free soldiers in the service of the Rus' princes), and peasants who had been free during the times of the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia.

[5] During the 12th and 13th centuries, fortified villages were built by Kievan Rus' and Galician princes to defend the local lucrative salt trade and the borders with the Kingdoms of Poland and Hungary.

These villages were located southwest of Lviv and Przemyśl in areas such as those surrounding Sambir, which in modern times have been the heartland for Ukrainian noble settlement.

After the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia was absorbed by Jagiellonian Poland in the 14th century as the Ruthenian Voivodeship, the noble status of these poor boyars and druzhina was confirmed in exchange for military service to the Polish Crown; those poor boyars who failed to confirm their noble status were reduced to the level of serfs or, more frequently, town servants and assimilated into those social groups.

They also point out that those arguing in favour the Polish origins, while writing about the Polonization of wealthy landowning boyars (nobles), completely ignore the documented existence of poor boyars and druzhina who inhabited western Ukraine before Polish rule and failed to account for what happened to this large group of people after western Ukrainian lands were absorbed by Poland.

[6] Furthermore, given that the Polish culture was dominant and that for centuries Poles controlled the local administration, it seems unrealistic that large numbers of Poles would assimilate to the subservient Ukrainian culture and to adopt the Ukrainian Orthodox or Greek Catholic faiths, which were at a disadvantage relative to the Polish Roman Catholic religion.

Their relative poverty served as a barrier to assimilation with the wealthy Polish landowners and helped them to retain their East Slavic identity.

Due to their shared Orthodox faith, when the Moldavian prince Bogdan III the One-Eyed invaded Polish-controlled Galicia in 1509, the local Ukrainian nobles joined this invasion en masse.

[8] Opposition from the western Ukrainian nobles delayed the implementation of the Union of Brest, the recognition by the Orthodox Church in Ukraine of the Pope, by several decades in Galicia.

The relative poverty of the Ukrainian nobility was evident in the fact that few owned armour, very few could afford to come on horseback, and they were typically armed only with sabres, muskets or even small calibre bird-hunting rifles.

The Western Ukrainian nobility, whose self-image was centred on their function of militarily defending the kingdom, found themselves without a social role within the new political circumstances and from this point defined themselves largely by their differences from and superiority to the peasants.

Unlike serfs, Ukrainian nobles were also not obligated to perform communal duty such as working on roads, which they considered to be humiliating.

The nobility attempted to continue to unofficially elect their own leaders, traditionally known as prefects, despite official integration with the peasant community.

[6] Multiple appeals to the Austrian government in the 1860s seeking to obtain separate legal standings for themselves failed, with rare exceptions such as sometimes being able to avoid having to perform compulsory roadwork.

Villages populated mostly by the Ukrainian nobility tended to vote for Polish candidates and to oppose efforts to spread literacy among the peasants.

The nobility were often treated as scapegoats and blamed for electoral failures; the press of the national movement accused them of greed and of selling their votes to the Poles.

[10] Almost none of the 19th-century political activists seeking to alleviate the plight of Ukrainian peasants, or to spread literacy, or to encourage Ukrainization, or to limit economic exploitation, were nobles.

By the end of that century, however, the idea of the old multinational Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth gave way to competing modern Ukrainian and Polish nationalisms.

[7] The nobility was represented by the Association of the Ruthenian Gentry, which allied itself with the conservative and religious elements within the Ukrainian national movement.

[10] Russophiles attempted to exploit the differences between nobles and peasants, and there was a stronger tendency to support ideological Russophilia among the nobility than among the general Galician population.

Indeed, the noble candidate from Sambir county in the elections of 1911, Ivan Kulchytsky, even declared "now we have recovered our sight and shall not allow the bastards to trick us with Ukraine….

By the beginning of the 20th century, noble gatherings often concluded with the singing of the Ukrainian national anthem, Shche ne vmerla Ukraina ("Ukraine has not yet Died").

[11] Yevhen Petrushevych, president of the West Ukrainian People's Republic was from a family of noble priests who traced their origins to Galician boyars.

Based in the traditional heartland of western Ukrainian nobility, the town of Sambir, its first head was the priest Petro Sas-Pohoretsky.

Reflecting some exposure to education, the noble speech was also differentiated from that of the peasants by the frequent use of Polish and Latin words and expressions.

Western Ukrainian nobles typically lived in small one or two-room houses with straw roofs whose interiors were in most ways indistinguishable from those of the peasants.

Following the wedding ceremony, young noblemen would fire their pistols into the air as a way of saluting the new pair and wishing them a long life.

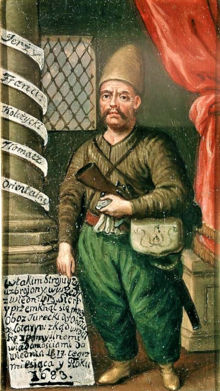

[14] Clothing served a very important function for the nobles because after they lost their legal privileges in the early 19th century, manner of dressing was one of the few ways they could demonstrate that they were different from the peasants.

Members of the nobility, regardless of level of education, typically knew the distant history and exploits of their families and would pass these stories on to their children.