Politics of France

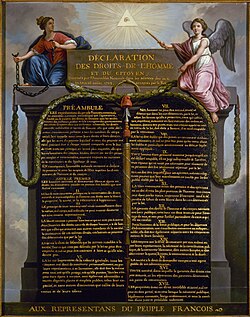

[1] The constitution provides for a separation of powers and proclaims France's "attachment to the Rights of Man and the principles of National Sovereignty as defined by the Declaration of 1789".

It passes statutes and votes on the budget; it controls the action of the executive through formal questioning on the floor of the houses of Parliament and by establishing commissions of inquiry.

While France is a unitary state, its administrative subdivisions—regions, departments and communes—have various legal functions, and the national government is prohibited from intruding into their normal operations.

[3] A popular referendum approved the constitution of the French Fifth Republic in 1958, greatly strengthening the authority of the presidency and the executive with respect to Parliament.

[6] Though the president may not de jure dismiss the prime minister, nevertheless, if the prime minister is from the same political side, they can, in practice, have them resign on demand (De Gaulle is said to have initiated this practice "by requiring undated letters of resignation from his nominees to the premiership," though more recent presidents have not necessarily used this method[7]).

When parties from opposite ends of the political spectrum control parliament and the presidency, the power-sharing arrangement is known as cohabitation.

With the term of the president shortened to five years, and with the presidential and parliamentary elections separated by only a few months, this is less likely to happen[needs update].

In the 2022 presidential election President Macron was re-elected after beating his far-right rival, Marine Le Pen, in the runoff.

However, this is not guaranteed, and, on occasion, the opinion of the majority parliamentarians may differ significantly from those of the executive, which often results in a large number of amendments.

As of 2006[update], the use of this article was the "First Employment Contract" proposed by Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin,[15] a move that greatly backfired.

Contrary to a sometimes used polemical cliché, that dates from the French Third Republic of 1870–1940, with its decrees-law (décrets-lois), neither the president nor the prime minister may rule by decree (outside of the narrow case of presidential emergency powers).

They are also sometimes used to push controversial legislation through, such as when Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin created new forms of work contracts in 2005.

The government also provides for watchdogs over its own activities; these independent administrative authorities are headed by a commission typically composed of senior lawyers or of members of the Parliament.

For instance, appointments, except for the highest positions (the national directors of agencies and administrations), must be made solely on merit (typically determined in competitive exams) or on time in office.

Certain civil servants have statuses that prohibit executive interference; for instance, judges and prosecutors may be named or moved only according to specific procedures.

In addition, each minister has a private office, which is composed of members whose nomination is politically determined, called the cabinet.

In addition, the government owns and controls all, or the majority, of shares of some companies, like Electricité de France, SNCF or Areva.

The government has a strong influence in shaping the agenda of Parliament (the cabinet has control over the parliamentary order of business 50% of the time, 2 out of 4 weeks per month).

This, and the indirect mode of election, prompted socialist Lionel Jospin, who was prime minister at the time, to declare the Senate an "anomaly".

Because of the importance of allowing government and social security organizations to proceed with the payment of their suppliers, employees, and recipients, without risk of a being stopped by parliamentary discord, these bills are specially constrained.

Proponents of the cumul allege that having local responsibilities ensures that members of parliament stay in contact with the reality of their constituency; also, they are said to be able to defend the interest of their city etc.

It does not play a role in the adoption of statutes and regulations, but advises the lawmaking bodies on questions of social and economic policies.

The Court is often solicitated by various state agencies, parliamentary commissions, and public regulators, but it can also petitioned to act by any French citizen or organization operating in France.

In 2008, the office was enshrined in the French Constitution and three years later, in 2011, it was renamed Défenseur des droits (Defender of Rights).

In agreement with the principles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the general rule is that of freedom, and law should only prohibit actions detrimental to society.

There also exist secondary regulation called arrêtés, issued by ministers, subordinates acting in their names, or local authorities; these may only be taken in areas of competency and within the scope delineated by primary legislation.

However, in 1982, the national government passed legislation to decentralize authority by giving a wide range of administrative and fiscal powers to local elected officials.

In March 1986, regional councils were directly elected for the first time, and the process of decentralization has continued, albeit at a slow pace.

In March 2003, a constitutional revision has changed very significantly the legal framework towards a more decentralized system and has increased the powers of local governments.

(Sociologist Jean Viard noted [Le Monde, 22 Feb 2006] that half of all conseillers généraux were still fils de paysans, i.e. sons of peasants, suggesting France's deep rural roots).

|

|

This section needs to be

updated

.

(

October 2022

)

|