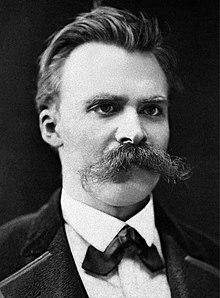

Friedrich Nietzsche's views on women

At times he could speak both in praise and in contempt of women, as in the following passage: "What inspires respect for woman, and often enough even fear, is her nature, which is more “natural” than man's, the genuine, cunning suppleness of a beast of prey, the tiger's claw under the glove, the naiveté of her egoism, her uneducatability and inner wildness, the incomprehensibility, scope, and movement of her desires and virtues."

His attitude can sometimes be entirely disparaging: "From the beginning, nothing has been more alien, repugnant, and hostile to woman than truth—her great art is the lie, her highest concern is mere appearance and beauty. "

[5] Kelly Oliver and Marilyn Pearsall have even suggested that Nietzsche's philosophy cannot be understood or analyzed apart from his remarks on women.

They opine that, even though Nietzsche's work has been useful in the development of some feminist theory, it cannot be considered feminist per se: "While Nietzsche challenges traditional hierarchies between mind and body, reason and irrationality, nature and culture, truth and fiction — hierarchies that have been used to degrade and exclude women — his remarks about women and his use of feminine and maternal metaphors throughout his writings confound attempts simply to proclaim Nietzsche a champion of feminism or women.

Cornelia Klinger states in her book Continental Philosophy in Feminist Perspective: "Nietzsche, like Schopenhauer a prominent hater of women, at least relativizes his savage statements about woman-as-such.

"[7] One of Nietzsche's own statements is cited in support of this assertion:"Whenever a cardinal problem is at stake, there speaks an unchangeable "this is I"; about man and woman, for example, a thinker cannot relearn but only finish learning–only discover ultimately how this is "settled in him."

(Beyond Good and Evil, Section 231) Frances Nesbitt Oppel interprets Nietzsche's attitude towards women as part of a rhetorical strategy....Nietzsche's apparent misogyny is part of his overall strategy to demonstrate that our attitudes toward sex-gender are thoroughly cultural, are often destructive of our own potential as individuals and as a species, and may be changed.

What looks like misogyny may be understood as part of a larger strategy whereby "woman-as-such" (the universal essence of woman with timeless character traits) is shown to be a product of male desire, a construct.

"[9] Babette Babich takes up this same quote as above, recognizing that "[a]lthough Nietzsche as generously as ever saves his commentators the labor of interpretation, the problem recurs precisely because of the nature of what he proceeds to call his truths."