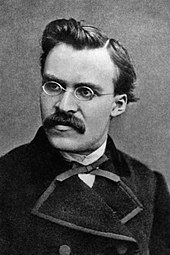

Influence and reception of Friedrich Nietzsche

According to a recent study, "Gustav Landauer, Emma Goldman and others reflected on the chances offered and the dangers posed by these ideas in relation to their own politics.

Heated debates over meaning, for example on the will to power or on the status of women in Nietzsche’s works, provided even the most vehement critics such as Peter Kropotkin with productive cues for developing their own theories.

In recent times, a newer strand called post-anarchism has invoked Nietzsche’s ideas, while also disregarding the historical variants of Nietzschean anarchism.

"[17] Some hypothesize on certain grounds Nietzsche's violent stance against anarchism may (at least partially) be the result of a popular association during this period between his ideas and those of Max Stirner.

[19] Spencer Sunshine writes, "There were many things that drew anarchists to Nietzsche: his hatred of the state; his disgust for the mindless social behavior of "herds"; his anti-Christianity; his distrust of the effect of both the market and the state on cultural production; his desire for an "overman" — that is, for a new human who was to be neither master nor slave; his praise of the ecstatic and creative self, with the artist as his prototype, who could say, "Yes" to the self-creation of a new world on the basis of nothing; and his forwarding of the "transvaluation of values" as source of change, as opposed to a Marxist conception of class struggle and the dialectic of a linear history.

According to the French fascist Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, it was the Nietzschean emphasis on the autotelic power of the Will that inspired the mystic voluntarism and political activism of his comrades.

Such politicized readings were vehemently rejected by another French writer, the socialo-communist anarchist Georges Bataille, who in the 1930s sought to establish (in ambiguous success) the "radical incompatibility" between Nietzsche (as a thinker who abhorred mass politics) and "the fascist reactionaries."

[26] The German philosopher Martin Heidegger, an active member of the Nazi Party, noted that everyone in his day was either 'for' or 'against' Nietzsche while claiming that this thinker heard a "command to reflect on the essence of a planetary domination."

In particular, the gesture of setting up 'Nietzsche' as a battlefield on which to take one's stand against or to enter into competition with the ideas of one's intellectual predecessors or rivals has happened quite frequently in the twentieth century.

"[27] Contrary to Bataille, Thomas Mann, Albert Camus and others, claimed that the Nazi movement, despite Nietzsche' virulent hatred of both volkist-populist socialist and nationalism ("national socialism"), did, in certain of its emphases, share an affinity with Nietzsche's ideas, including his ferocious attacks against democracy, egalitarianism, the communistic-socialistic social model, popular Christianity, parliamentary government, and a number of other things.

not a Germanic master race but a neo-imperial elite of culturally refined "redeemers" of humanity, which was otherwise considered wretched and plebeian and ugly in its mindless existence.

Despite the fact that Nietzsche had expressed his disgust with plebeian-volkist antisemitism and supremacist German nationalism in the most forthright terms possible (e.g. he resolved "to have nothing to do with anyone involved in the perfidious race-fraud"), phrases like "the will to power" became common in Nazi circles.

"[33] According to Steven Aschheim, "Classical Zionism, that essentially secular and modernizing movement, was acutely aware of the crisis of Jewish tradition and its supporting institutions.

Nietzsche was enlisted as an authority for articulating the movement's ruptured relationship with the past and a force in its drive to normalization and its activist ideal of self-creating Hebraic New Man.

"[34] Francis R. Nicosia notes, "At the height of his fame between 1895 and 1902, some of Nietzsche's ideas seemed to have a particular resonance for some Zionists, including Theodor Herzl.

"[36] However, Gabriel Sheffer suggests that Herzl was too bourgeois and too eager to be accepted into mainstream society to be much of a revolutionary (even an "aristocratic" one), and hence could not have been strongly influenced by Nietzsche, but remarks, "Some East European Jewish intellectuals, such as the writers Yosef Hayyim Brenner and Micha Josef Berdyczewski, followed after Herzl because they thought that Zionism offered the chance for a Nietzschean 'transvaluation of values' within Jewry".

Martin Buber was fascinated by Nietzsche, whom he praised as a heroic figure, and he strove to introduce "a Nietzschean perspective into Zionist affairs."

In 1901, Buber, who had just been appointed the editor of Die Welt, the primary publication of the World Zionist Organization, published a poem in Zarathustrastil (a style reminiscent of Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra) calling for the return of Jewish literature, art and scholarship.

[38] Max Nordau, an early Zionist orator and controversial racial anthropologist, insisted that Nietzsche had been insane since birth, and advocated "branding his disciples [...] as hysterical and imbecile.

[44] Yet Jones also reports that Freud emphatically denied that Nietzsche's writings influenced his own psychological discoveries; in the 1890s, Freud, whose education at the University of Vienna in the 1870s had included a strong relationship with Franz Brentano, his teacher in philosophy, from whom he had acquired an enthusiasm for Aristotle and Ludwig Feuerbach, was acutely aware of the possibility of convergence of his own ideas with those of Nietzsche and doggedly refused to read the philosopher as a result.

In his excoriating — but also sympathetic — critique of psychoanalysis, The Psychoanalytic Movement, Ernest Gellner depicts Nietzsche as setting out the conditions for elaborating a realistic psychology, in contrast with the eccentrically implausible Enlightenment psychology of Hume and Smith, and assesses the success of Freud and the psychoanalytic movement as in large part based upon its success in meeting this "Nietzschean minimum".

[45] Early twentieth-century thinkers who read or were influenced by Nietzsche include: philosophers Martin Heidegger, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Ernst Jünger, Theodor Adorno, Georg Brandes, Martin Buber, Karl Jaspers, Henri Bergson, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Leo Strauss, Michel Foucault, Julius Evola, Emil Cioran, Miguel de Unamuno, Lev Shestov, Ayn Rand, José Ortega y Gasset, Rudolf Steiner and Muhammad Iqbal; sociologists Ferdinand Tönnies and Max Weber; composers Richard Strauss, Alexander Scriabin, Gustav Mahler, and Frederick Delius; historians Oswald Spengler, Fernand Braudel[46] and Paul Veyne, theologians Paul Tillich and Thomas J.J. Altizer; the occultists Aleister Crowley and Erwin Neutzsky-Wulff.

Novelists Franz Kafka, Joseph Conrad, Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse, Charles Bukowski, André Malraux, Nikos Kazantzakis, André Gide, Knut Hamsun, August Strindberg, James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence, Vladimir Bartol and Pío Baroja; psychologists Sigmund Freud, Otto Gross, C. G. Jung, Alfred Adler, Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, Rollo May and Kazimierz Dąbrowski; poets John Davidson, Rainer Maria Rilke, Wallace Stevens and William Butler Yeats; painters Salvador Dalí, Wassily Kandinsky, Pablo Picasso, Mark Rothko; playwrights George Bernard Shaw, Antonin Artaud, August Strindberg, and Eugene O'Neill; and authors H. P. Lovecraft, Olaf Stapledon, Menno ter Braak, Richard Wright, Robert E. Howard, and Jack London.

The theme of the aesthetic justification of existence Nietzsche introduced from his earliest writings, in "The Birth of Tragedy" declaring sublime art as the only metaphysical consolation of existence; and in the context of fascism and Nazism, the Nietzschean aestheticization of politics void of morality and ordered by caste hierarchy in service of the creative caste, has posed many problems and questions for thinkers in contemporary times.

[...] The effect of both is immeasurably great, even greater in general thinking than in technical philosophy Bertrand Russell in his History of Western Philosophy was scathing in his chapter on Nietzsche, asking whether his work might not be called the "mere power-phantasies of an invalid" and referring to Nietzsche as a "megalomaniac": It is obvious that in his day-dreams he is a warrior, not a professor; all of the men he admires were military.

[47] The appropriation of Nietzsche's work by the Nazis, combined with the rise of analytic philosophy, ensured that British and American academic philosophers would almost completely ignore him until at least 1950.

According to the philosopher René Girard,[48] Nietzsche's greatest political legacy lies in his 20th-century French interpreters, among them Georges Bataille, Pierre Klossowski, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze (and Félix Guattari), and Jacques Derrida.