Frisian freedom

Throughout the Middle Ages, Frisians resisted the expansion of feudalism into their lands, fighting a series of wars against the County of Holland in order to maintain their autonomy.

Frisians formed treaties with other powers to protect their freedom, which was recognised by a number of German kings during the Late Middle Ages.

During the Dutch Revolt, it was used to argue for the restoration of rights lost under Habsburg rule, and Frisian freedom later inspired American and French Revolutionaries.

[1] Beginning in the mid-11th century, Medieval communes spread from northern Italy across much of Europe, gathering strength in areas outside the authority of feudal lords.

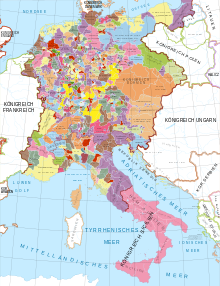

[2] Within the Holy Roman Empire, some of these communes, including in Frisia, eliminated the power of local princes, establishing quasi-republican systems of government.

[4] Although Frisia was officially brought under the rule of the Holy Roman Empire, a de facto system of self-governance developed in the region.

Rural communes became the dominant institutional form in Frisia, with higher-level subdivisions coalescing into self-governing districts, known as communitates terrae (West Frisian: Steatsmienskippen; German: Landesgemeinden).

[16] In 1323, the "Ubstalsboom Laws" were promulgated, declaring that "if any prince, secular or ecclesiastical, [...] shall have assailed us, Frisians, or any of us, wanting to subject us to the yoke of servitude, then together, through a joint call-up and by force of arms, we shall protect our liberty.

"[17] The French Bartholomaeus Anglicus also recognised the Frisians' freedom from feudal rule and serfdom, as well as their annual election of judges, writing that they "hazard their life for liberty and prefer death to being oppressed by the yoke of servitude".

[24] In 1248, William II of Holland confirmed "all the rights, liberties and privileges conceded to all Frisians by the emperor Charlemagne", but the terms were kept vague, so the decree had little significant effect.

[31] A chronicle at the Aduard Abbey also recognised that the Frisians "utterly abhorred the state of servitude for reason of the severity of the princes, as they had experienced earlier.

"[17] A largely leaderless society, from 1298, references began to be made to urban officeholders known as aldermen and elected military leaders known as haedlingen, which were often compared to the Italian podestà.

[36] Although the Frisian freedom was abolished, the Saxons ultimately struggled to introduce feudalism in west Frisia, as the local haedlingen rejected moves to bring them into the nobility.

[37] The concept of the Frisian freedom was reinterpreted during the Dutch Revolt, when it was used to argue for the reinstatement of historic rights that had been lost under Habsburg rule.

This reconception has been disputed by academic historians, who have pointed out that the national myth was retroactively constructed in the 19th century and have debated the historical continuity of the Frisian freedom.