Frontispiece (architecture)

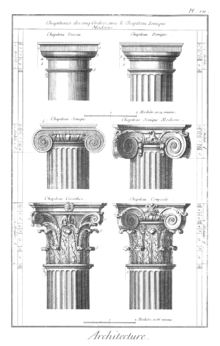

[1] The earliest and most notable variation of frontispieces can be seen in Ancient Greek Architecture[2] which features a large triangular gable, known as a pediment, usually supported by a collection of columns.

[4] With the proliferation of minimalistic ideas in 21st century architecture, a large emphasis is placed on simplicity and practicality when designing the façades of buildings.

[10] Some architectural authors have also interchangeably used "frontispiece" with the word "pediment" in recent years given the similar nature of the ornaments involved.

Especially seen in ancient Greece and Rome, frontispieces were often used to depict mythological gods or even important figures in society depending on the purpose and patrons of the building.

[6] Broken pediments, made prominent in Baroque Architecture, can be identified by their non-continuous triangular outline, usually open at the top apex.

Many well-preserved examples of Roman influenced frontispieces can be found in Provence, France due to the use of ‘fine quality building stone’ while others constructed with a decorative veneer were quickly lost.

[4] Classical elements, such as superimposed orders, were reintroduced in the sixteenth century to dignify the entrances to some important houses and some collegiate buildings.

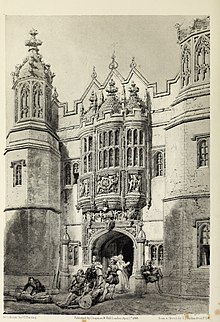

[4] In the late 1520s to early 1530s, there was a revival of the heavy use of dense classical ornaments on the frontispieces which can be seen on the facade of Hengrave Hall, Suffolk, England built in 1538,[4] as well as the addition of elements distinctive of the Italian Renaissance such as the use of terracotta moulded decorative elements[23] featured on the façade of the hall entrance to Richard Weston’s Sutton Place, Surrey, built in 1533.

[26] It was noted by Richard John Riddell, who analysed entrance-porticos in English Renaissance architecture, that the most impressive and architecturally sophisticated frontispieces were often set against houses 'by men who enjoyed or aspired to preferment and high office, with the immense political power and social prestige, and by academics who wished to give permanent expression to the distinction of their college and university'.

[4] Frontispieces of this nature were purely for applied and decorative functions, even the 'fullest extent of the role of the columns in their load-bearing capacity was to hold up each other and not the building'.

[4] In baroque architecture, frontispieces also took on semi-oval structures which decorated the tops of the entrances with added embellishments synonymous to the household or building.

Another known example of this is seen in Andrea Palladio’s Church of San Giorgio Maggiore, in Venice which features an unusual broken pediment as it is the result of superimposing two temple fronts.

[29] These moves towards minimalism can be seen in the proliferation of the Wabi-sabi aesthetics, popularised in Japan which translates roughly to ‘the elegant beauty of humble simplicity’,[28] encapsulating Taoist and Buddhist ideologies of accepting nature and ‘favouring the imperfect and incomplete in everything’.