Fullerene

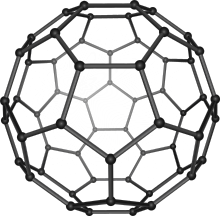

The closed fullerenes, especially C60, are also informally called buckyballs for their resemblance to the standard ball of association football ("soccer").

[7] IUPAC defines fullerenes as "polyhedral closed cages made up entirely of n three-coordinate carbon atoms and having 12 pentagonal and (n/2-10) hexagonal faces, where n ≥ 20.

[12][13] In 1973, independently from Henson, D. A. Bochvar and E. G. Galpern made a quantum-chemical analysis of the stability of C60 and calculated its electronic structure.

Around 1980, Sumio Iijima identified the molecule of C60 from an electron microscope image of carbon black, where it formed the core of a particle with the structure of a "bucky onion".

[15] Also in the 1980s at MIT, Mildred Dresselhaus and Morinobu Endo, collaborating with T. Venkatesan, directed studies blasting graphite with lasers, producing carbon clusters of atoms, which would be later identified as "fullerenes.

[17] The name "buckminsterfullerene" was eventually chosen for C60 by the discoverers as an homage to American architect Buckminster Fuller for the vague similarity of the structure to the geodesic domes which he popularized; which, if they were extended to a full sphere, would also have the icosahedral symmetry group.

Kroto, Curl, and Smalley were awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry[19] for their roles in the discovery of this class of molecules.

[20][21] After their discovery, minute quantities of fullerenes were found to be produced in sooty flames,[22] and by lightning discharges in the atmosphere.

[3] The production techniques were improved by many scientists, including Donald Huffman, Wolfgang Krätschmer, Lowell D. Lamb, and Konstantinos Fostiropoulos.

In 2010, the spectral signatures of C60 and C70 were observed by NASA's Spitzer infrared telescope in a cloud of cosmic dust surrounding a star 6500 light years away.

[5] Kroto commented: "This most exciting breakthrough provides convincing evidence that the buckyball has, as I long suspected, existed since time immemorial in the dark recesses of our galaxy.

"[6] According to astronomer Letizia Stanghellini, "It’s possible that buckyballs from outer space provided seeds for life on Earth.

[25][26] There are two major families of fullerenes, with fairly distinct properties and applications: the closed buckyballs and the open-ended cylindrical carbon nanotubes.

[27] However, hybrid structures exist between those two classes, such as carbon nanobuds — nanotubes capped by hemispherical meshes or larger "buckybuds".

One proposed use of carbon nanotubes is in paper batteries, developed in 2007 by researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

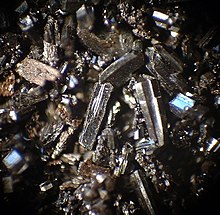

[43] B80 was experimentally obtained in 2024, i.e. 17 years after theoretical prediction by Gonzalez Szwacki et al..[44] Inorganic (carbon-free) fullerene-type structures have been built with the molybdenum(IV) sulfide (MoS2), long used as a graphite-like lubricant, tungsten (WS2), titanium (TiS2) and niobium (NbS2).

[56] In mathematical terms, the combinatorial topology (that is, the carbon atoms and the bonds between them, ignoring their positions and distances) of a closed-shell fullerene with a simple sphere-like mean surface (orientable, genus zero) can be represented as a convex polyhedron; more precisely, its one-dimensional skeleton, consisting of its vertices and edges.

[60] Evidence for a meteor impact at the end of the Permian period was found by analyzing noble gases preserved by being trapped in fullerenes.

This has been shown to be the case using quantum chemical modelling, which showed the existence of strong diamagnetic sphere currents in the cation.

Under high pressure and temperature, buckyballs collapse to form various one-, two-, or three-dimensional carbon frameworks.

Single-strand polymers are formed using the Atom Transfer Radical Addition Polymerization (ATRAP) route.

Such treatment converts fullerite into a nanocrystalline form of diamond which has been reported to exhibit remarkable mechanical properties.

The sp2-hybridized carbon atoms, which are at their energy minimum in planar graphite, must be bent to form the closed sphere or tube, which produces angle strain.

The characteristic reaction of fullerenes is electrophilic addition at 6,6-double bonds, which reduces angle strain by changing sp2-hybridized carbons into sp3-hybridized ones.

[72] Fullerenes are normally electrical insulators, but when crystallized with alkali metals, the resultant compound can be conducting or even superconducting.

The alternative "top-down" approach claims that fullerenes form when much larger structures break into constituent parts.

Minor perturbations involving the breaking of a few molecular bonds cause the cage to become highly symmetrical and stable.

If the structure of the fullerene does not allow such numbering, another starting atom was chosen to still achieve a spiral path sequence.

[82] The toxicity of these carbon nanoparticles is not only dose- and time-dependent, but also depends on a number of other factors such as: It was recommended to assess the pharmacology of every new fullerene- or metallofullerene-based complex individually as a different compound.

In a humorously speculative 1966 column for New Scientist, David Jones suggested the possibility of making giant hollow carbon molecules by distorting a plane hexagonal net with the addition of impurity atoms.

540 , another member of the family of fullerenes

60 with isosurface of ground state electron density as calculated with DFT

60 , one kind of fullerene

70 has 10 additional atoms (shown in red) added to C

60 and a hemisphere rotated to fit

60 in solution

60 in extra virgin olive oil, showing the characteristic purple color of pristine C

60 solutions