Scanning electron microscope

[2][3] Although Max Knoll produced a photo with a 50 mm object-field-width showing channeling contrast by the use of an electron beam scanner,[4] it was Manfred von Ardenne who in 1937 invented[5] a microscope with high resolution by scanning a very small raster with a demagnified and finely focused electron beam.

The signals used by a SEM to produce an image result from interactions of the electron beam with atoms at various depths within the sample.

[citation needed] Secondary electrons have very low energies on the order of 50 eV, which limits their mean free path in solid matter.

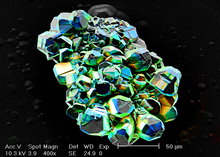

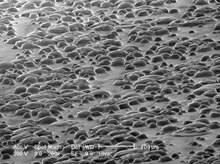

Due to the very narrow electron beam, SEM micrographs have a large depth of field yielding a characteristic three-dimensional appearance useful for understanding the surface structure of a sample.

Metal objects require little special preparation for SEM except for cleaning and conductively mounting to a specimen stub.

Conductive materials in current use for specimen coating include gold, gold/palladium alloy, platinum, iridium, tungsten, chromium, osmium,[14] and graphite.

The high-pressure region around the sample in the ESEM neutralizes charge and provides an amplification of the secondary electron signal.

[citation needed] Low-voltage SEM is typically conducted in an instrument with a field emission guns (FEG) which is capable of producing high primary electron brightness and small spot size even at low accelerating potentials.

[citation needed] Embedding in a resin with further polishing to a mirror-like finish can be used for both biological and materials specimens when imaging in backscattered electrons or when doing quantitative X-ray microanalysis.

The main preparation techniques are not required in the environmental SEM outlined below, but some biological specimens can benefit from fixation.

[18] Cryo-fixed specimens may be cryo-fractured under vacuum in a special apparatus to reveal internal structure, sputter-coated and transferred onto the SEM cryo-stage while still frozen.

[24] Low-temperature scanning electron microscopy (LT-SEM) is also applicable to the imaging of temperature-sensitive materials such as ice[25][26] and fats.

[27] Freeze-fracturing, freeze-etch or freeze-and-break is a preparation method particularly useful for examining lipid membranes and their incorporated proteins in "face on" view.

The fractured surface is cut to a suitable size, cleaned of any organic residues, and mounted on a specimen holder for viewing in the SEM.

[28] Unlike optical and transmission electron microscopes, image magnification in an SEM is not a function of the power of the objective lens.

Provided the electron gun can generate a beam with a sufficiently small diameter, an SEM could in principle work entirely without condenser or objective lenses.

The secondary electrons are first collected by attracting them towards an electrically biased grid at about +400 V, and then further accelerated towards a phosphor or scintillator positively biased to about +2,000 V. The accelerated secondary electrons are now sufficiently energetic to cause the scintillator to emit flashes of light (cathodoluminescence), which are conducted to a photomultiplier outside the SEM column via a light pipe and a window in the wall of the specimen chamber.

Semiconductor detectors can be made in radial segments that can be switched in or out to control the type of contrast produced and its directionality.

Cathodoluminescence and EBIC are referred to as "beam-injection" techniques, and are very powerful probes of the optoelectronic behavior of semiconductors, in particular for studying nanoscale features and defects.

Over the last decades, cathodoluminescence was most commonly experienced as the light emission from the inner surface of the cathode-ray tube in television sets and computer CRT monitors.

[30] Conventional SEM requires samples to be imaged under vacuum, because a gas atmosphere rapidly spreads and attenuates electron beams.

Processes involving phase transitions, such as the drying of adhesives or melting of alloys, liquid transport, chemical reactions, and solid-air-gas systems, in general cannot be observed with conventional high-vacuum SEM.

[31] The first commercial development of the ESEM in the late 1980s[32][33] allowed samples to be observed in low-pressure gaseous environments (e.g. 1–50 Torr or 0.1–6.7 kPa) and high relative humidity (up to 100%).

This was made possible by the development of a secondary-electron detector[34][35] capable of operating in the presence of water vapour and by the use of pressure-limiting apertures with differential pumping in the path of the electron beam to separate the vacuum region (around the gun and lenses) from the sample chamber.

This is useful because coating can be difficult to reverse, may conceal small features on the surface of the sample and may reduce the value of the results obtained.

ESEM may be the preferred for electron microscopy of unique samples from criminal or civil actions, where forensic analysis may need to be repeated by several different experts.

By using the images produced by the SEM, forensic scientists can compare diatoms types to confirm the body of water a person died in.

[43] Most SEM manufacturers now (2018) offer such a built-in or optional four-quadrant BSE detector, together with proprietary software to calculate a 3D image in real time.

[52] Other approaches use more sophisticated (and sometimes GPU-intensive) methods like the optimal estimation algorithm and offer much better results[53] at the cost of high demands on computing power.

[citation needed] SEM is also used by art conservationists to discern threats to paintings' surface stability due to aging, such as the formations of complexes of zinc ions with fatty acids.

Top: backscattered electron analysis – composition

Bottom: secondary electron analysis – topography