Fundamental theorem of calculus

The fundamental theorem of calculus is a theorem that links the concept of differentiating a function (calculating its slopes, or rate of change at each point in time) with the concept of integrating a function (calculating the area under its graph, or the cumulative effect of small contributions).

The first part of the theorem, the first fundamental theorem of calculus, states that for a continuous function f , an antiderivative or indefinite integral F can be obtained as the integral of f over an interval with a variable upper bound.

[1] Conversely, the second part of the theorem, the second fundamental theorem of calculus, states that the integral of a function f over a fixed interval is equal to the change of any antiderivative F between the ends of the interval.

The fundamental theorem of calculus relates differentiation and integration, showing that these two operations are essentially inverses of one another.

Ancient Greek mathematicians knew how to compute area via infinitesimals, an operation that we would now call integration.

The origins of differentiation likewise predate the fundamental theorem of calculus by hundreds of years; for example, in the fourteenth century the notions of continuity of functions and motion were studied by the Oxford Calculators and other scholars.

The first published statement and proof of a rudimentary form of the fundamental theorem, strongly geometric in character,[2] was by James Gregory (1638–1675).

Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) systematized the knowledge into a calculus for infinitesimal quantities and introduced the notation used today.

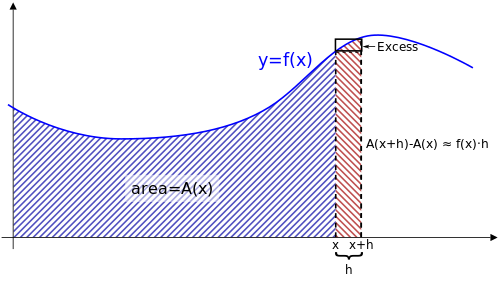

whose graph is plotted as a curve, one defines a corresponding "area function"

As shown in the accompanying figure, h is multiplied by f(x) to find the area of a rectangle that is approximately the same size as this strip.

Intuitively, the fundamental theorem states that integration and differentiation are inverse operations which reverse each other.

By summing up all these small steps, you can approximate the total distance traveled, in spite of not looking outside the car:

(To obtain your highway-marker position, you would need to add your starting position to this integral and to take into account whether your travel was in the direction of increasing or decreasing mile markers.)

[6] Let f be a continuous real-valued function defined on a closed interval [a, b].

for all x in (a, b) so F is an antiderivative of f. The fundamental theorem is often employed to compute the definite integral of a function

the latter equality resulting from the basic properties of integrals and the additivity of areas.

According to the mean value theorem for integration, there exists a real number

Now, we add each F(xi) along with its additive inverse, so that the resulting quantity is equal:

Each rectangle, by virtue of the mean value theorem, describes an approximation of the curve section it is drawn over.

By taking the limit of the expression as the norm of the partitions approaches zero, we arrive at the Riemann integral.

Part I of the theorem then says: if f is any Lebesgue integrable function on [a, b] and x0 is a number in [a, b] such that f is continuous at x0, then

On the real line this statement is equivalent to Lebesgue's differentiation theorem.

[10] In higher dimensions Lebesgue's differentiation theorem generalizes the Fundamental theorem of calculus by stating that for almost every x, the average value of a function f over a ball of radius r centered at x tends to f(x) as r tends to 0.

Conversely, if f is any integrable function, then F as given in the first formula will be absolutely continuous with F′ = f almost everywhere.

The fundamental theorem can be generalized to curve and surface integrals in higher dimensions and on manifolds.

One such generalization offered by the calculus of moving surfaces is the time evolution of integrals.

One of the most powerful generalizations in this direction is the generalized Stokes theorem (sometimes known as the fundamental theorem of multivariable calculus):[13] Let M be an oriented piecewise smooth manifold of dimension n and let

be a smooth compactly supported (n − 1)-form on M. If ∂M denotes the boundary of M given its induced orientation, then

The theorem is often used in situations where M is an embedded oriented submanifold of some bigger manifold (e.g. Rk) on which the form

The fundamental theorem of calculus allows us to pose a definite integral as a first-order ordinary differential equation.