Representation theory

Representation theory is a branch of mathematics that studies abstract algebraic structures by representing their elements as linear transformations of vector spaces, and studies modules over these abstract algebraic structures.

, the standard n-dimensional space of column vectors over the real or complex numbers, respectively.

[17] The first uses the idea of an action, generalizing the way that matrices act on column vectors by matrix multiplication.

Isomorphic representations are, for practical purposes, "the same"; they provide the same information about the group or algebra being represented.

[19] The definition of an irreducible representation implies Schur's lemma: an equivariant map

are representations of a Lie algebra, then the correct formula to use is[22] This product can be recognized as the coproduct on a coalgebra.

In the case of the representation theory of the group SU(2) (or equivalently, of its complexified Lie algebra

Then the tensor product decomposes as a direct sum of one copy of each representation with label

Although, all the theories have in common the basic concepts discussed already, they differ considerably in detail.

Over a field of characteristic zero, the representation of a finite group G has a number of convenient properties.

This is a consequence of Maschke's theorem, which states that any subrepresentation V of a G-representation W has a G-invariant complement.

Maschke's theorem holds more generally for fields of positive characteristic p, such as the finite fields, as long as the prime p is coprime to the order of G. When p and |G| have a common factor, there are G-representations that are not semisimple, which are studied in a subbranch called modular representation theory.

Averaging techniques also show that if F is the real or complex numbers, then any G-representation preserves an inner product

Unitary representations are automatically semisimple, since Maschke's result can be proven by taking the orthogonal complement of a subrepresentation.

[26] Nevertheless, Richard Brauer extended much of character theory to modular representations, and this theory played an important role in early progress towards the classification of finite simple groups, especially for simple groups whose characterization was not amenable to purely group-theoretic methods because their Sylow 2-subgroups were "too small".

[30] A major goal is to describe the "unitary dual", the space of irreducible unitary representations of G.[31] The theory is most well-developed in the case that G is a locally compact (Hausdorff) topological group and the representations are strongly continuous.

Although irreducible unitary representations must be "admissible" (as Harish-Chandra modules) and it is easy to detect which admissible representations have a nondegenerate invariant sesquilinear form, it is hard to determine when this form is positive definite.

[11] A major goal is to provide a general form of the Fourier transform and the Plancherel theorem.

If the group is neither abelian nor compact, no general theory is known with an analogue of the Plancherel theorem or Fourier inversion, although Alexander Grothendieck extended Tannaka–Krein duality to a relationship between linear algebraic groups and tannakian categories.

Harmonic analysis has also been extended from the analysis of functions on a group G to functions on homogeneous spaces for G. The theory is particularly well developed for symmetric spaces and provides a theory of automorphic forms (discussed below).

[36] The classification of representations of solvable Lie groups is intractable in general, but often easy in practical cases.

In contrast, the finite-dimensional representations of semisimple Lie algebras are completely understood, after work of Élie Cartan.

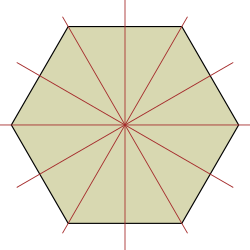

The representation of 𝖌 can be decomposed into weight spaces that are eigenspaces for the action of 𝖍 and the infinitesimal analogue of characters.

The structure of semisimple Lie algebras then reduces the analysis of representations to easily understood combinatorics of the possible weights that can occur.

Although linear algebraic groups have a classification that is very similar to that of Lie groups, their representation theory is rather different (and much less well understood) and requires different techniques, since the Zariski topology is relatively weak, and techniques from analysis are no longer available.

[40] Invariant theory studies actions on algebraic varieties from the point of view of their effect on functions, which form representations of the group.

Classically, the theory dealt with the question of explicit description of polynomial functions that do not change, or are invariant, under the transformations from a given linear group.

Important results in the theory include the Selberg trace formula and the realization by Robert Langlands that the Riemann–Roch theorem could be applied to calculate the dimension of the space of automorphic forms.

As a result, an entire philosophy, the Langlands program has developed around the relation between representation and number theoretic properties of automorphic forms.

In the case where C is VectF, the category of vector spaces over a field F, this definition is equivalent to a linear representation.