Infinity

In the 17th century, with the introduction of the infinity symbol[1] and the infinitesimal calculus, mathematicians began to work with infinite series and what some mathematicians (including l'Hôpital and Bernoulli)[2] regarded as infinitely small quantities, but infinity continued to be associated with endless processes.

For example, Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem implicitly relies on the existence of Grothendieck universes, very large infinite sets,[5] for solving a long-standing problem that is stated in terms of elementary arithmetic.

The earliest recorded idea of infinity in Greece may be that of Anaximander (c. 610 – c. 546 BC) a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher.

"[10] It has also been maintained, that, in proving the infinitude of the prime numbers, Euclid "was the first to overcome the horror of the infinite".

Nevertheless, his paradoxes,[15] especially "Achilles and the Tortoise", were important contributions in that they made clear the inadequacy of popular conceptions.

As a member of the Eleatics school which regarded motion as an illusion, he saw it as a mistake to suppose that Achilles could run at all.

Achilles does overtake the tortoise; it takes him The Jain mathematical text Surya Prajnapti (c. 4th–3rd century BCE) classifies all numbers into three sets: enumerable, innumerable, and infinite.

for such a number in his De sectionibus conicis,[19] and exploited it in area calculations by dividing the region into infinitesimal strips of width on the order of

[23] Hermann Weyl opened a mathematico-philosophic address given in 1930 with:[24] Mathematics is the science of the infinite.The infinity symbol

[26] It was introduced in 1655 by John Wallis,[27][28] and since its introduction, it has also been used outside mathematics in modern mysticism[29] and literary symbology.

[30] Gottfried Leibniz, one of the co-inventors of infinitesimal calculus, speculated widely about infinite numbers and their use in mathematics.

In this context, it is often useful to consider meromorphic functions as maps into the Riemann sphere taking the value of

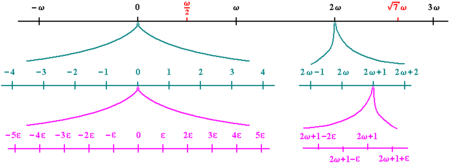

The infinities in this sense are part of a hyperreal field; there is no equivalence between them as with the Cantorian transfinites.

This modern mathematical conception of the quantitative infinite developed in the late 19th century from works by Cantor, Gottlob Frege, Richard Dedekind and others—using the idea of collections or sets.

If a set is too large to be put in one-to-one correspondence with the positive integers, it is called uncountable.

Cantor's views prevailed and modern mathematics accepts actual infinity as part of a consistent and coherent theory.

.This hypothesis cannot be proved or disproved within the widely accepted Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory, even assuming the Axiom of Choice.

The first of these results is apparent by considering, for instance, the tangent function, which provides a one-to-one correspondence between the interval (−π/2, π/2) and R.The second result was proved by Cantor in 1878, but only became intuitively apparent in 1890, when Giuseppe Peano introduced the space-filling curves, curved lines that twist and turn enough to fill the whole of any square, or cube, or hypercube, or finite-dimensional space.

[45] Until the end of the 19th century, infinity was rarely discussed in geometry, except in the context of processes that could be continued without any limit.

"[50] Cosmologists have long sought to discover whether infinity exists in our physical universe: Are there an infinite number of stars?

By travelling in a straight line with respect to the Earth's curvature, one will eventually return to the exact spot one started from.

If so, one might eventually return to one's starting point after travelling in a straight line through the universe for long enough.

[51] The curvature of the universe can be measured through multipole moments in the spectrum of the cosmic background radiation.

To date, analysis of the radiation patterns recorded by the WMAP spacecraft hints that the universe has a flat topology.

An easy way to understand this is to consider two-dimensional examples, such as video games where items that leave one edge of the screen reappear on the other.

[55] The concept of infinity also extends to the multiverse hypothesis, which, when explained by astrophysicists such as Michio Kaku, posits that there are an infinite number and variety of universes.

[57] In logic, an infinite regress argument is "a distinctively philosophical kind of argument purporting to show that a thesis is defective because it generates an infinite series when either (form A) no such series exists or (form B) were it to exist, the thesis would lack the role (e.g., of justification) that it is supposed to play.

This allows artists to create paintings that realistically render space, distances, and forms.

[64][65] Cognitive scientist George Lakoff considers the concept of infinity in mathematics and the sciences as a metaphor.

This perspective is based on the basic metaphor of infinity (BMI), defined as the ever-increasing sequence <1, 2, 3, …>.