Civil funeral celebrant

Best practice is for celebrants to interview the family, prepare and check the eulogy, brief those giving reminiscences and provide resources and suggestions that will assist the family choose aspects of the ceremony such as the music, video and photo presentations, quotations (poetry and prose) and symbols.

This was in the sense that the client sought a service from Messenger, as a government appointed civil celebrant and as a professional ceremony provider.

[4]: 157 There had occasionally been secular funeral ceremonies before this date, but they were extremely rare and informal, e.g. some words spoken at the graveside by members of the Communist party.

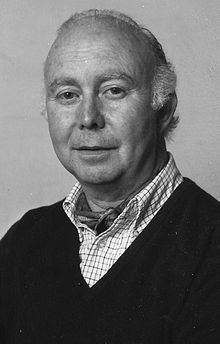

However, Lionel Murphy, then a judge of the High Court of Australia, encouraged Messenger to go out into the "highways and byways" and find non-marriage celebrants to fulfil the societal need.

[4]: 161 Murphy urged Messenger and his colleagues to prepare each ceremony well, to charge a reasonable fee to ensure long term sustainability, and to see the civil ceremony as a cultural bridge between ordinary people and the rich world of the visual and performing arts - especially music,[12] English literature, and poetry.

[4]: 99 The few marriage celebrants of that time (1975-1976) involved - notably Dally Messenger III and Marjorie Messenger - were in the years and months following (to 1980) joined by non-marriage celebrants Brian McInerney, Diane Storey, Dawn Dickson, Jean Nugent, Ken Woodburn and Jan Tully.

It was clear that skills such as creative writing and public speaking, a knowledge of suitable poetic, literary, symbolic and musical resources, an awareness of punctuality and time, appropriate dress and similar were essential.

The Australian lecture tour of a renowned scholar in this area, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, organised by funeral celebrant Diane Storey, received wide media publicity and was credited with changing social attitudes to death and dying.

[4]: 226 & 260 It was agreed that adequate training of celebrants must leave them capable of providing the standards the general public expected such as full personal interaction and cooperation with the family, careful preparation of a historical and personal eulogy, attentive choosing of readings (poetry and prose), music, choreography (processionals and recessionals), symbolism, and an appropriate setting and place for the ceremony.

In short, funeral ceremonies were viewed as a serious responsibility which should be prepared with efficiency and attention to detail, requiring an attitude of genuineness, empathy and compassion.

[9] The high ideals of the original celebrants and the ones who slowly joined their ranks changed the nature of the funeral ceremony scene in Melbourne and Victoria.

This high standard is well acknowledged by Tony Walter, lecturer and reader in Death and Society at the University of Reading in the UK.

[18] International acknowledgement was provided by a comprehensive article in the US news magazine Time (2004) reporting that in the "liberal" cities of Melbourne, Australia, and Auckland, New Zealand, civil celebrants "conduct substantially more than half of the funerals".

But it also cited an alternative point of view by atheist sociologist Mira Crouch who stated that celebrant funerals were "mawkish and sentimental".

[4]: 91 Rick Barclay was voted in as president, Dally Messenger III as secretary, and Ken Woodburn as treasurer.

[16] Funeral directors in states of Australia other than Victoria still refused to pay celebrants any more than they paid clergy i.e. a low "stipend" or "offering".

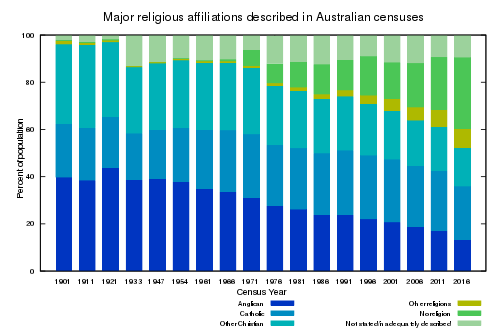

[19]As church attendances declined, funeral directors in New South Wales pushed non-church people into organising "family ceremonies".

Funeral directors in Australia, who effectively controlled fees for celebrants, held out against any increases in payments.

The loss of support for celebrants due to the retirements of idealist funeral directors such as Rob and John Allison and Desmond Tobin was keenly felt.

[1] The Humanist Society of England and Scotland, after many visits to Australia in the 1980s, established a wide network of quality funeral celebrants characterised by a strong non-religious stance.

[24] The Institute of Civil Funerals (IoCF), on the other hand, has a more family-centred approach and its members include as little or as much religion as requested.