Rune

[10] Other Germanic terms derived from *rūnō include *runōn ('counsellor'), *rūnjan and *ga-rūnjan ('secret, mystery'), *raunō ('trial, inquiry, experiment'), *hugi-rūnō ('secret of the mind, magical rune'), and *halja-rūnō ('witch, sorceress'; literally '[possessor of the] Hel-secret').

[11] It is also often part of personal names, including Gothic Runilo (𐍂𐌿𐌽𐌹𐌻𐍉), Frankish Rúnfrid, Old Norse Alfrún, Dagrún, Guðrún, Sigrún, Ǫlrún, Old English Ælfrún, and Lombardic Goderūna.

Their procedure for casting lots is uniform: They break off the branch of a fruit tree and slice into strips; they mark these by certain signs and throw them, as random chance will have it, on to a white cloth.

Then a state priest, if the consultation is a public one, or the father of the family, if it is private, prays to the gods and, gazing to the heavens, picks up three separate strips and reads their meaning from the marks scored on them.

[30]As Victoria Symons summarizes, "If the inscriptions made on the lots that Tacitus refers to are understood to be letters, rather than other kinds of notations or symbols, then they would necessarily have been runes, since no other writing system was available to Germanic tribes at this time.

Notably the j, s, and ŋ runes undergo considerable modifications, while others, such as p and ï, remain unattested altogether prior to the first full futhark row on the Kylver Stone (c. 400 AD).

[citation needed] The 6th-century Björketorp Runestone warns in Proto-Norse using the word rune in both senses: Haidzruno runu, falahak haidera, ginnarunaz.

Charm words, such as auja, laþu, laukaʀ, and most commonly, alu,[34] appear on a number of Migration period Elder Futhark inscriptions as well as variants and abbreviations of them.

[35] Nevertheless, it has proven difficult to find unambiguous traces of runic "oracles": although Norse literature is full of references to runes, it nowhere contains specific instructions on divination.

There are at least three sources on divination with rather vague descriptions that may, or may not, refer to runes: Tacitus's 1st-century Germania, Snorri Sturluson's 13th-century Ynglinga saga, and Rimbert's 9th-century Vita Ansgari.

There, the "chips" fell in a way that said that he would not live long (Féll honum þá svo spánn sem hann mundi eigi lengi lifa).

One of these accounts is the description of how a renegade Swedish king, Anund Uppsale, first brings a Danish fleet to Birka, but then changes his mind and asks the Danes to "draw lots".

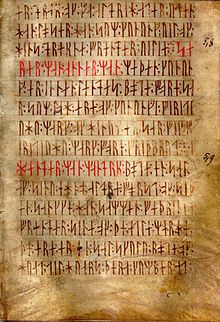

[39] These inscriptions were made on wood and bone, often in the shape of sticks of various sizes, and contained information of an everyday nature—ranging from name tags, prayers (often in Latin), personal messages, business letters, and expressions of affection, to bawdy phrases of a profane and sometimes even of a vulgar nature.

This is attested as early as on the Noleby Runestone from c. 600 AD that reads Runo fahi raginakundo toj[e'k]a..., meaning "I prepare the suitable divine rune..."[40] and in an attestation from the 9th century on the Sparlösa Runestone, which reads Ok rað runaʀ þaʀ rægi[n]kundu, meaning "And interpret the runes of divine origin".

The poem relates how Ríg, identified as Heimdall in the introduction, sired three sons—Thrall (slave), Churl (freeman), and Jarl (noble)—by human women.

When Jarl reached an age when he began to handle weapons and show other signs of nobility, Ríg returned and, having claimed him as a son, taught him the runes.

The earliest known sequential listing of the full set of 24 runes dates to approximately AD 400 and is found on the Kylver Stone in Gotland, Sweden.

[citation needed] Some examples of futhorc inscriptions are found on the Thames scramasax, in the Vienna Codex, in Cotton Otho B.x (Anglo-Saxon rune poem) and on the Ruthwell Cross.

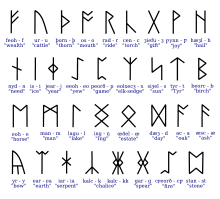

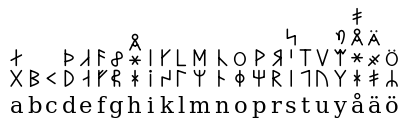

The Anglo-Saxon rune poem gives the following characters and names: ᚠ feoh, ᚢ ur, ᚦ þorn, ᚩ os, ᚱ rad, ᚳ cen, ᚷ gyfu, ᚹ ƿynn, ᚻ hægl, ᚾ nyd, ᛁ is, ᛄ ger, ᛇ eoh, ᛈ peorð, ᛉ eolh, ᛋ sigel, ᛏ tir, ᛒ beorc, ᛖ eh, ᛗ mann, ᛚ lagu, ᛝ ing, ᛟ œthel, ᛞ dæg, ᚪ ac, ᚫ æsc, ᚣ yr, ᛡ ior, ᛠ ear.

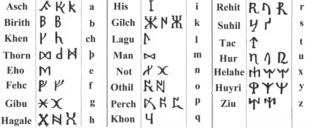

A runic alphabet consisting of a mixture of Elder Futhark with Anglo-Saxon futhorc is recorded in a treatise called De Inventione Litterarum, ascribed to Hrabanus Maurus and preserved in 8th- and 9th-century manuscripts mainly from the southern part of the Carolingian Empire (Alemannia, Bavaria).

The fact that each rune represents [both] a sound value and a word gives this writing system a multivalent quality that further distinguishes it from roman script.

The largest group of surviving Runic inscription are Viking Age Younger Futhark runestones, commonly found in Denmark and Sweden.

[citation needed] The pioneer of the Armanist branch of Ariosophy and one of the more important figures in esotericism in Germany and Austria in the late 19th and early 20th century was the Austrian occultist, mysticist, and völkisch author, Guido von List.

Various systems of Runic divination have been published since the 1980s, notably by Ralph Blum (1982), Stephen Flowers (1984, onward), Stephan Grundy (1990), and Nigel Pennick (1995).

In 2002, Swedish esotericist Thomas Karlsson popularized this "Uthark" runic row, which he refers to as, the "night side of the runes", in the context of modern occultism.

They also were used in the initial drafts of The Lord of the Rings, but later were replaced by the Cirth rune-like alphabet invented by Tolkien, used to write the language of the Dwarves, Khuzdul.

[citation needed] Runes feature extensively in many video games that incorporate themes from early Germanic cultures, including Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice, Jøtun, Northgard and God of War.

They are used for a range of purposes including as names, symbols, decoration and on runestones that provide information about Nordic mythology and background for the game's narrative.

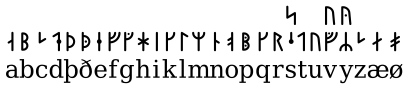

Role-playing games, such as the Ultima series, use a runic font for in-game signs and printed maps and booklets, and Metagaming's The Fantasy Trip used rune-based cipher for clues and jokes throughout its publications.

As of Unicode 7.0 (2014), eight characters were added, three representing J. R. R. Tolkien's mode of writing Modern English in Anglo-Saxon runes, and five for the "cryptogrammic" vowel symbols used in an inscription on the Franks Casket.