G.I. coffeehouses

[1]: 121 In addition, while not called coffeehouses, there were at least two Labor Canteens created near the end of World War II which promoted racial integration and demobilization of the troops.

Gardner later wrote of that time: "By 1967 the Army was filling up with people who would rather be making love to the music of Jimi Hendrix than war to the lies of Lyndon Johnson.

[8] Gardner and Mickleson rented a space at 1732 Main Street in downtown Columbia turning it into a counterculture coffeehouse complete with photos of Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin along with many rock posters and alternative newspapers from around the country like the Berkeley Barb and The Village Voice.

"[1]: 21 In mid-February 1968 "thirty-five uncertain but determined soldiers gathered [in uniform] in front of the main post chapel" for a pray-in to express "grave concern" about the war.

Most of the GIs were quickly disbursed by the Fort's MPs, who closed the post and surrounded the chapel, while two soldiers kneeling in prayer were "dragged away and placed in confinement".

Eventually all official charges against organizers and participants were dropped but, in a soon to become familiar pattern, the military found other ways to discipline the soldiers: two were sent to Vietnam, one to Korea and others were demoted.

The gathering eventually dispersed without incident but the next day the Fort Jackson command claimed the meeting was a "riot" and arrested nine members of GIs United.

The New York Times noted, "By harassing, restricting and arresting on dubious charges the leaders of an interracial militant enlisted group there called GIs United Against the War in Vietnam, Fort Jackson's Brass has produced a cause celebre out of all proportion to the known facts."

[9]: 118 Despite the difficulties at the UFO, the news of the early rapid development of GI antiwar activity at Fort Jackson spread quickly within the broader peace movement.

In addition, the chapel pray-in and the seemingly incongruous scene of GIs hanging out in a psychedelic coffeehouse attracted media attention, soon becoming national news.

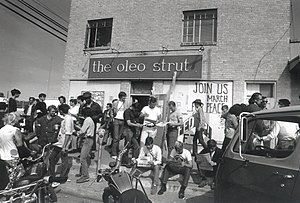

When Gardner left town to help set up other coffeehouses, Josh Gould and Janet "Jay" Lockard stepped in to become the principle operators of the soon to open Oleo Strut.

[1]: 30 [22] The Strut's grand opening, on July 5, 1968, was a counter-culture "love-in" at a local park that "included folk and rock performances, antiwar speeches, and copious amounts of marijuana".

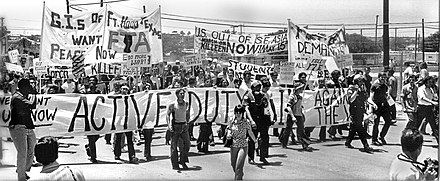

[1]: 31–32 [23][24]: 28 Considerable controversy arose among the troops at Fort Hood as thousands of GIs were being prepared for possible use against civilian demonstrators expected at the August 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

In an unprecedented act, a group of 60 black soldiers from the 1st Armored Division met on base to "discuss their opposition to Army racism and the use of troops against civilians".

She was quickly arrested by the military police and barred from the base, but told a press conference that afternoon that she did it "because GIs aren't allowed to distribute literature there, I think it's appalling that men who are sent overseas to fight and die for their country are denied the constitutional rights which they are supposed to be defending.

[27][28] Fonda's visit of May 11, 1970, gave an unexpected boost to the Fort Hood soldiers and their civilian supporters who were building for nationally coordinated antiwar demonstrations near military bases on May 16, Armed Forces Day.

They set up a counseling center that offered assistance with discharges and conscientious objector applications; education on GI rights and military law; and legal aid.

On February 16, an estimated 300 GIs led around 1,000 demonstrators through downtown Seattle to a rally at Tacoma's Eagles Auditorium where they listened to speeches against the war and racism, and for GI rights.

Seventeen of the GIs and three civilians, including Stapp, then sued the Secretary of Defense and the Fort Lewis commandant seeking to keep them "from prohibiting soldiers' meetings or disrupting them when they do occur.

At the University of Washington in Seattle a group of students organized what they called "the Trial of the Army", which on January 21 convened a panel of thirteen active-duty servicemen to listen to testimony about the Vietnam War and daily life in the military.

The "Trial" generated significant local and national publicity and probably contributed to the military's decision to cancel the hearing and abandon their efforts to declare the Shelter Half off limits.

The Armed Forces Journal characterized PCS activity as "legal help and incitement to dissident GIs" and illustrated this by describing their practice of "airdrop[ing] planeloads of seditious literature into Oakland's sprawling Army Base".

The local newspaper published letters urging physical attacks on the Wagon and its members and on November 21, 1971, the coffeehouse was burned to the ground by unknown arsonists.

This attack generated national media coverage, including an appeal for support published in The New York Review of Books and signed by a number of prominent people, but the cause of the fire was never investigated by the town's authorities.

[46] While the coffeehouse was open, it helped GIs organize demonstrations, pass out leaflets and put out the newspaper, and it hosted speeches by many well-known antiwar activists, including the FTA show, Howard Zinn, Dick Gregory and Country Joe McDonald.

[13][2][54] A 2017 broadcast on KQED public radio interviewed two of the early organizers at the Green Machine, Teresa Cerda and Cliff Mansker a black ex-Marine.

"[9]: 157 When in May 1970 the Quaker House was set on fire and forced to close, antiwar GIs regrouped and opened Haymarket Square in the heart of downtown Fayetteville before the end of the year.

[9]: 207 At the grand opening of Haymarket Square, "[t]wo hundred G.I.s filled the building to capacity" to hear notorious antiwar Vietnam veterans Susan Schnall, ex-Navy nurse, and Donald Duncan, ex-Army Green Beret "blast the war and military hierarchy".

In addition to the Open Sights GI paper, the coffeehouse helped establish a "wide network of organizers" at local bases, including the editors of The Oppressed at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and Liberated Castles at Fort Belvoir.

[1]: xi [2]: 127–8 While not called coffeehouses, there were at least two Labor Canteens created near the end of World War II which promoted racial integration and demobilization of the troops.