Stop Our Ship

Naval stations and ships on the West Coast from mid-1970 to the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, and at its height involved tens of thousands of antiwar civilians, military personnel and veterans.

As press coverage of the Constellation Project expanded, it drew the attention of antiwar activists from all over California, including Joan Baez and David Harris.

[12][13][14][15][16] In Congressional hearings in December 1972 Admiral David H.Bagley, the U.S. Navy's Chief of Naval Personnel testified that "considerable public interest was generated" by the campaign.

[23] He argued in a widely distributed pamphlet that aircraft carriers had become weapons "used to crush popular uprisings and to bully the weaker and poorer countries of the world.

The council encouraged city residents to "provide bedding, food, medical and legal help" to the sailors, and "passed a motion to establish a protected space where soldiers could access counseling and other support.”[32] Ten local churches also offered sanctuary.

[35][36][27][37] When the Coral Sea arrived in Hawaii in late November, it was greeted by a special performance in Honolulu of the FTA antiwar show, featuring Jane Fonda, Donald Sutherland, and Country Joe McDonald.

[43][4]: 113 With the ship at sea, copies of Kitty Litter continued to be published by civilian supporters and mailed to antiwar crewmen who circulated them on board and submitted articles.

[4]: 115 When the USS Midway left Naval Air Station Alameda in April 1972, sixteen enlisted men assigned to Fighter Squadron 151 on board the carrier signed an antiwar letter to President Nixon.

In San Diego, the local antiwar groups, including some of those who had waged the initial campaign against the USS Constellation, took their support to a more organized level by banding together in 1972 to form the Center for Servicemen’s Rights.

They rented a large storefront space in the middle of the main GI strip which contained a bookstore, mimeo, meeting rooms and a stage; staffed by a "collective of volunteers that included active duty sailors, a few Marines, veterans, and civilian activists.

"[50] They provided individual and group counselling on GI rights, conscience objection and other means of opposing the war, as well as support for sailors who wanted to publish their own newspapers, leaflets or articles.

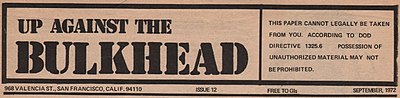

[4]: 116 The San Francisco underground GI newspaper Up Against the Bulkhead and its staff played an important role in supporting the SOS movement, particularly the dissident sailors of the Coral Sea.

[29][51][52] In January 1972, attorneys from the National Lawyers Guild, worked with several active duty sailors to create a support center in Olongapo, Philippines, just outside U.S.

And as the concerns of sailors for their safety at sea "became entangled with the enlarged Indochina war effort" it "led to protests against conditions that under other circumstances might have been bearable but, for the purpose of bombing Vietnam, were seen as intolerable”.

The U.S.’s new strategy “was torpedoed by a massive antiwar movement among the sailors, who combined escalating protests and rebellions with a wide-spread campaign of sabotage.”[6] The Navy's sudden need for additional personnel greatly intensified the pressure for new recruits and training.

Worried about the war and the unsafe conditions on board they contacted civilian antiwar organizations who helped them draw up a list of specific shipboard hazards, which they circulated, gathering signatures from 48 members of the crew.

The petition resulted in little change, but on April 24, 1972, as the ship was pulling out of port, it was greeted by an antiwar blockade of seventeen canoes and small boats.

When martial law was declared in the Philippines in September 1972, the U.S. Navy “used the occasion to crack down on so-called troublemakers and…loaded more than two hundred enlisted men from eleven different ships onto planes for immediate transfer back to San Diego.”[4]: 119 [63][64] Once in San Diego many of the men wanted to let the public know what had happened and on October 24 “a racially mixed group of thirty-one enlisted men held a press conference to denounce the deplorable conditions, harassment, and racial prejudice they encountered while at sea.”[4]: 119 Their statement, partially excerpted here, captured many of the issues swirling within the Navy at that time: We, the undersigned demand an end to the mistreatment and harassment that we have received from the United States Navy….

"[68][4]: p.121 Three Black marines were singled out as the "ringleaders", transported by helicopter to a military base in Da Nang and charged with mutiny, as well as assault, riot, and resisting arrest.

[67] They were then transferred to Okinawa, where they spent months in the brig with the military prosecutor "pushing for 65 years of prison" after being ordered by the Marine Corps to drop the mutiny charges as clearly excessive.

With the help of civilian lawyers and the prospect of charges of racism being aired during the trial, the military eventually backed down and settled for less than fully honorable discharges for the three.

“This [singling out of blacks only] was hard to understand in terms of the tensions” The New York Times quoted an officer saying “who had access to all of the reports of the incident.” One of those summoned brought “nine companions with him and grew belligerent”.

Prior to the meeting, however, the command “singled out fifteen members of Black Faction as agitators and ordered that six of them be given immediate less-than-honorable discharges.” At the same time, notice was given ship wide that 250 men would be administratively discharged.

Feeling they were being singled out for retaliation for their activism and fearing that most of the additional discharges would be directed at them, over one hundred sailors, including several whites, staged a sit in and refused to work on the morning of November 3.

[4]: 121–122 [73] During the day, members of the ship's Human Relations Council attempted to meet with the mutineers in a private dining room with little success as they demanded to see the captain.

Most of the men, however, refused to board the ship and on November 9 “staged a defiant dockside strike - perhaps the largest act of mass defiance in naval history.”[75] Despite these unprecedented actions, none of the sailors were arrested, most were simply reassigned to other duty stations, while a few received what were described as “trifling punishments”.

For example, in June 1970 the destroyer USS Richard B. Anderson “was kept from sailing to Vietnam for eight weeks when crew members deliberately wrecked an engine.”[6]: 65 But, in tandem with the SOS Movement, naval sabotage became an even more serious issue in 1972 as the air war dramatically expanded.

In March 1972 when the aircraft carrier USS Midway received orders for Vietnam, “dissident crewmen deliberately spilled three thousand gallons of oil into the bay.

The captain of the Constellation “told a press conference in November of 1972 that ‘saboteurs were at work’ during the period of unrest aboard his ship.” The Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet stated in October 1972 that the increase in sabotage was a “grave liability” to the ability of the Navy to operate.

They stated that the October 1972 redeployment of the Kitty Hawk to combat which resulted in riots and near mutiny was apparently “due to the incidents of sabotage aboard her sister ships USS Ranger and USS Forrestal.”[4]: 123–126 While the SOS movement had no cohesive central organization or leadership, it was united by the overarching, if ultimately un-attained, goal of stopping warships from entering combat in Indochina.