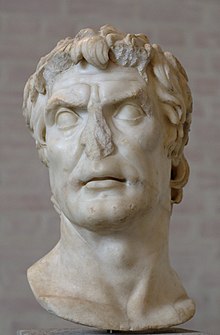

Gaius Marius

Rising from a family of smallholders in a village called Ceraetae in the district of Arpinum, Marius acquired his initial military experience serving with Scipio Aemilianus at the Siege of Numantia in 134 BC.

In the 19th century,[2] Marius was credited with the so-called Marian reforms, including the shift from militia levies to a professional soldiery; improvements to the pilum (a kind of javelin); and changes to the logistical structure of the Roman army.

[21][22] It is not clear, however, whether Plutarch's narrative history properly reflects how controversial this proposal in fact was; Cicero, writing during the Republic, describes this lex Maria as quite straightforward and uncontroversial.

[32] In 114 BC, Marius's imperium was prorogued and he was sent to govern the highly sought-after province of Further Spain (Latin: Hispania Ulterior) pro consule,[33] where he engaged in some sort of minor military operation to clear brigands from untapped mining areas.

[45] Sallust claims that this was catalysed, in part, by a fortune-teller in Utica who "declared that a great and marvellous career awaited him; the seer accordingly advised him, trusting in the gods, to carry out what he had in mind and put his fortune to the test as often as possible, predicting that all his undertakings would have a happy issue".

[49] Both groups wrote home in praise of him, suggesting that he could end the war quickly, unlike Metellus, who was pursuing a policy of methodically subduing the countryside.

[58] Seeking troops to bolster the forces in Numidia and win his promised quick victory, Marius found it difficult to recruit from Rome's traditional source of manpower, property-holding men.

[61] With more troops mustering in southern Italy, Marius sailed for Africa, leaving his cavalry in the hands of his newly elected quaestor, Lucius Cornelius Sulla.

The standard narrative is that after a series of manpower shortages,[75] Marius received a dispensation to recruit volunteers from the poorest census class, the proletarii, for the war against Jugurtha in 107 BC.

[85] Other reforms attributed to Marius include the abolition of the citizen cavalry and light infantry, a redesign of the pilum, a standardised eagle standard for all legions, and the substitution of the cohort for the maniple.

[97] The Republic, altogether lacking generals who had recently concluded military campaigns successfully,[98] took the illegal step of electing Marius in absentia for a second consulship in three years.

[109] An appeal by a young tribune, Lucius Appuleius Saturninus, in a public meeting before the vote – along with a field of candidates without great name recognition – allowed Marius to be returned as consul again in 102 BC.

[122] After election, he returned to Rome to announce his victory at Aquae Sextiae, deferred a triumph, and promptly marched north with his army to join Catulus,[123][124] whose command was prorogued since Marius's consular colleague was dispatched to defeat a slave revolt in Sicily.

[132] Having saved the Republic from destruction and at the height of his political powers, Marius desired another consulship to secure land grants for his veteran volunteers and to ensure he received appropriate credit for his military successes.

[133] Marius was duly returned as consul for 100 BC with Lucius Valerius Flaccus;[134] according to Plutarch, he also campaigned on behalf of his colleague so to prevent his rival Metellus Numidicus from securing a seat.

[135] During the year of Marius's sixth consulship (100 BC), Lucius Appuleius Saturninus was tribune of the plebs for the second time and advocated reforms like those earlier put forth by the Gracchi.

However, seeing that opposition was impossible, Marius decided to travel to the east to Galatia in 98 BC, ostensibly to fulfil a vow he had made to the goddess Magna Mater.

[156][157] Plutarch portrays this voluntary exile as a great humiliation for the six-time consul: "considered obnoxious to the nobles and to the people alike", he was even forced to abandon his candidature for the censorship of 97.

[156] Other scholars have argued that the mission was instead planned by the Senate with the support of the princeps senatus Marcus Aemilius Scaurus for the purpose of investigating Mithridates' campaigns in Cappadocia without arousing too much suspicion.

[169] Lupus fell to a Marsic ambush on 11 June 90 BC while crossing the river Tolenus; Marius, commanding a different wing of the army, was yet able to drive the enemy back with heavy losses.

[171] After taking command over the northern front of the war, Marius moved energetically forward, defeating the Marsi with his former legate Sulla's help on hilly ground south of the Fucine Lake; Herius Asinius, a praetor of the Marrucini, was among the slain.

[175] The war was immensely hard fought but drew to an end within the next few years, as the Romans brought the lex Julia in 90 BC, granting citizenship to all the allies who were loyal or would otherwise promptly put down arms.

[182] After Sulla left Rome to prepare for his army in Nola to depart for the east, Sulpicius had his measures passed into law, and tacked on a rider which unprecedentedly appointed Marius – now a private citizen lacking any office in the Republic[183] – to the command in Pontus.

[187] The ancient sources say that Sulla's soldiers pledged their loyalty because they were worried that they would be kept in Italy while Marius raised troops from his own veterans who would then proceed to plunder great riches.

[f] Plutarch says of him: if Marius could have been persuaded to sacrifice to the Greek Muses and Graces, he would not have put the ugliest possible crown upon a most illustrious career in field and forum, nor have been driven by the blasts of passion, ill-timed ambition, and insatiable greed upon the shore of a most cruel and savage old age.

[219] However, that Marius died "so hated by contemporaries is really rather unremarkable, because to his unrealistic, even senile, dreams of further triumphs may be laid the prime cause for the disastrous civil war of 87 [BC]... His unquenchable ambitio overcame an unusually astute sense of judgement; the result, the beginning of the Roman revolution".

[221] In the narratives of Plutarch and Sallust, Marius's reforms to the recruitment process for the Roman legions are roundly criticised for creating a soldiery wholly loyal to their generals and beholden to their beneficence or ability to secure payment from the state.

[219] The similar use of the Assemblies in an attempt to replace Sulla with Marius for the Mithridatic War was unprecedented, as never before had laws been passed to confer commands on someone lacking any official title in the state.

[232] Marius's legal strategy misfired disastrously because he failed to predict Sulla's reaction of marching on the city to protect his command:[207] It was plainly expected that Sulpicius's bill and the sanctity of the law, even if much abused, would be obeyed without question... Sulla's unforeseen rejection of the 'popular' will, which he must surely have believed to have been of equivocal legality, was made from a position of great strength since he had the means and the opportunity to impose his will on the situation.

[215][h] The use of the Assemblies eroded senatorial control which, along with Sulla's decision to march on Rome, created significant and prolonged instability, only resolved by the destruction of the Republican form of government and the transition to Empire.

: Roman victories.

: Roman victories.

: Cimbric and Teutonic victories.

: Cimbric and Teutonic victories.