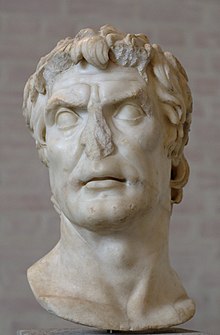

Quintus Sertorius

However, he soon returned in early 80 BC, taking in and leading many Marian and Cinnan exiles in a prolonged war, representing himself as a Roman proconsul resisting the Sullan regime at Rome.

He gathered support from other Roman exiles and the native Iberian tribes – in part by using his tamed white fawn to claim he had divine favour – and employed irregular and guerrilla warfare to repeatedly defeat commanders sent from Rome to subdue him.

He successfully sustained his anti-Sullan resistance for many years, despite substantial efforts to subdue him by the Sullan regime and its generals Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius and Pompey.

[12] Having inherited his father's clients, like many other young rural aristocrats (domi nobiles), Sertorius sought to begin a political career and thus moved to Rome in his mid-to-late teens trying to make it big as an orator and jurist.

[17] Sertorius' first recorded campaign was under Quintus Servilius Caepio as a staff officer and ended at the Battle of Arausio in 105 BC, where he showed unusual courage.

The local Roman garrison was hated by the natives for their lack of discipline and constant drinking, and Sertorius either arrived too late to stop their impropriety or was unable to.

Probably arriving at dawn, the town opened the gates for Sertorius and his men, convinced they were their warriors returning with loot from the slain Roman garrison.

[34] His quaestorship was unusual in that he largely governed the province while the actual governor, perhaps Gaius Coelius Caldus, spent time across the Alps subduing remnants of the Cimbric invasion.

[67] After Suessa, Sertorius departed to Etruria where he raised yet another army, some 40 cohorts, as the Etruscans, having gained their Roman citizenship through the Marian regime, were fearful of a Sullan victory.

Plutarch sums up the events: Cinna was murdered and against the wishes of Sertorius, and against the law, the younger Marius took the consulship while such [ineffectual] men as Carbo, Norbanus, and Scipio had no success in stopping Sulla's advance on Rome, so the Marian cause was being ruined and lost; cowardice and weakness by the generals played its part, and treachery did the rest, and there was no reason why Sertorius should stay to watch things going from bad to worse through the inferior judgement of men with superior power.

[74] Sertorius persuaded the local chieftains to accept him as the new governor and endeared himself to the general population by cutting taxes, and then began to construct ships and levy soldiers in preparation for the armies he expected to be sent after him by Sulla.

Sulla's forces, probably three or four legions[80] under the command of Gaius Annius Luscus, departed for Hispania early in 81 or very late in 82 BC, but were unable to break through the Pyrenees until Salinator was assassinated by P. Calpurnius Lanarius, one of his subordinates, who defected to the Sullans.

He fled to Nova Carthago and with 3,000 of his most loyal followers set sail to Mauritania, perhaps attempting some sort of attack on the coastal cities to keep his forces together, but was driven off by the locals.

Sertorius engaged this superior fleet in a naval battle to avoid allowing them to disembark,[81] but adverse winds broke most of his lighter ships, and he eventually fled the islands.

Sertorius followed them to Africa in the fall of 81 or the spring of 80 BC, rallied the locals in the vicinity of Tingis, and defeated Ascalis' men and the pirates in battle.

[118] Soon after, probably in late 77 BC, Sertorius was joined by Marcus Perperna Veiento, with a following of Roman and Italian aristocrats and a sizeable Roman-style army of fifty-three cohorts.

Afterward, he called together representatives of the Iberian tribes, thanked them for their aid in providing arms for his troops, discussed the progress of the war and the advantages they would have if he was victorious, and then dismissed them.

[120] By the 76 BC campaigning season, Pompey had recruited a large army, some 30,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry from his father and Sulla's veterans, its size being evidence of the threat posed by Sertorius to the Sullan Senate.

[141] Unwilling to fight two armies who would outnumber him if joined, Sertorius decamped, bitterly commenting: Now if the old woman had not made an appearance, I'd have thrashed the boy and packed him off to Rome.

[145] After the battle Sertorius reverted to guerrilla warfare, having lost the heavy infantry Perperna had lent to his cause which enabled him to match the Sullan legions in the field.

[146] Sertorius convinced Metellus and Pompey that he intended to remain besieged, and eventually broke through their lines, rejoined with a fresh Sertorian army, and resumed the war.

[170] Pompey subsequently eliminated Perperna's army and killed the rest of Sertorius' assassins and top Roman staff due to their proscribed status.

[177] During Gaius Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars, when his lieutenant Publius Licinius Crassus was conquering Aquitania in 56 BC, the Gauls sent ambassadors to many surrounding tribes for help, including Iberians from Hispania Citerior.

[187] Similarly, Konrad believes Plutarch conceived the Life of Sertorius as the character study of "a gifted yet imperfect man struggling against an unkind fate, to no avail".

[190] Plutarch wrote that "He [Sertorius] was more continent than Philip, more faithful to his friends than Antigonus, and more merciful to his enemies than Hannibal; and that for prudence and judgment he gave place to none of them, but in fortune was inferior to them all".

[193] Modern accounts that do not directly deal with Sertorius largely describe him and his war in terms of its impact on the Roman state, and his influence on the career of Pompey the Great.

[199] Pompey's highly irregular career was initiated by the aftermath of the civil wars of Sulla and Marius, but it was the strong military threat Sertorius posed which necessitated his extraordinary, illegal, effectively proconsular command and thereby deteriorated the Senate's control over the Roman army.

[64] Spann agrees, suggesting that Sertorius' central legacy was that his revolt "decisively transformed 'Sulla's Pupil' into Pompeius Magnus", whose prominence was to play a role in influencing yet further civil wars.

[205] Ironically, the defeat of Sertorius (and thus the last Marian resistance) may have caused the repealing of several of Sulla's laws, as there was no longer "fear that the [Sullan] structure itself might crumble".

[206] According to Steel, Sertorius' seizure of Hispania was "highly significant" as a display, similar to Sulla in his civil war, of how Roman foreign policy in the late second century relied greatly on domestic affairs.