Galen

[4][5][6] Considered to be one of the most accomplished of all medical researchers of antiquity, Galen influenced the development of various scientific disciplines, including anatomy,[7] physiology, pathology,[8] pharmacology,[9] and neurology, as well as philosophy[10] and logic.

The son of Aelius Nicon, a wealthy Greek architect with scholarly interests, Galen received a comprehensive education that prepared him for a successful career as a physician and philosopher.

Born in the ancient city of Pergamon (present-day Bergama, Turkey), Galen traveled extensively, exposing himself to a wide variety of medical theories and discoveries before settling in Rome, where he served prominent members of Roman society and eventually was given the position of personal physician to several emperors.

While dissections and vivisections on humans were practiced in Alexandria by Herophilus and Erasistratus in the 3rd century BCE under Ptolemaic permission, by Galen's time these proceedures were strictly forbidden in the Roman Empire.

Consequently, Galen had to resort to the dissection and vivisection of animals, particularly barbary apes and pigs, as Aristotle had done centuries earlier for the study of anatomy and physiology.

[14] His anatomical reports remained uncontested until 1543, when printed descriptions and illustrations of human dissections were published in the seminal work De humani corporis fabrica by Andreas Vesalius,[15][16] where Galen's physiological theory was accommodated to these new observations.

[19][20][21][22] Galen was very interested in the debate between the rationalist and empiricist medical sects,[23] and his use of direct observation, dissection, and vivisection represents a complex middle ground between the extremes of those two viewpoints.

[6] His father, Aelius Nicon, was a wealthy patrician, an architect and builder, with eclectic interests including philosophy, mathematics, logic, astronomy, agriculture and literature.

At that time Pergamon (modern-day Bergama, Turkey) was a major cultural and intellectual centre, noted for its library, second only to that in Alexandria,[8][30] as well as being the site of a large temple to the healing god Asclepius.

[6][12] Following his earlier liberal education, Galen at age 16 began his studies at the prestigious local healing temple or asclepeion as a θεραπευτής (therapeutes, or attendant) for four years.

Over his four years there, he learned the importance of diet, fitness, hygiene, and preventive measures, as well as living anatomy, and the treatment of fractures and severe trauma, referring to their wounds as "windows into the body".

Only five deaths among the gladiators occurred while he held the post, compared to sixty in his predecessor's time, a result that is in general ascribed to the attention he paid to their wounds.

[12] When the Peripatetic philosopher Eudemus became ill with quartan fever, Galen felt obliged to treat him "since he was my teacher and I happened to live nearby".

[40] Rome was engaged in foreign wars in 161; Marcus Aurelius and his then co-Emperor and adoptive brother Lucius Verus were in the north fighting the Marcomanni.

[42] Galen continued to work and write in his final years, finishing treatises on drugs and remedies as well as his compendium of diagnostics and therapeutics, which would have much influence as a medical text both in the Latin Middle Ages and Medieval Islam.

His dissections and vivisections of animals led to key observations that helped him accurately describe the human spine, spinal cord, and vertebral column.

[64][22] The rational soul controlled higher level cognitive functioning in an organism, for example, making choices or perceiving the world and sending those signals to the brain.

Several schools of thought existed within the medical field during Galen's lifetime, the main two being the Empiricists and Rationalists (also called Dogmatists or Philosophers), with the Methodists being a smaller group.

The Methodists mainly utilized pure observation, showing greater interest in studying the natural course of ailments than making efforts to find remedies.

His book contained directions on how to provide counsel to those with psychological issues to prompt them to reveal their deepest passions and secrets, and eventually cure them of their mental deficiency.

[80] The most complete compendium of Galen's writings, surpassing even modern projects like the Corpus Medicorum Graecorum/Latinorum [de], is the one compiled and translated by Karl Gottlob Kühn of Leipzig between 1821 and 1833.

[79] One of Hunayn's Arabic translations, Kitab ila Aglooqan fi Shifa al Amrad, which is extant in the Library of Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine & Sciences, is regarded as a masterpiece of Galen's literary works.

[89] The influence of Galen's writings, including humorism, remains strong in modern Unani medicine, now closely identified with Islamic culture, and widely practiced from India (where it is officially recognized) to Morocco.

From the 11th century onwards, Latin translations of Islamic medical texts began to appear in the West, alongside the Salerno school of thought, and were soon incorporated into the curriculum at the universities of Naples and Montpellier.

Unlike pagan Rome, Christian Europe did not exercise a universal prohibition of the dissection and autopsy of the human body and such examinations were carried out regularly from at least the 13th century.

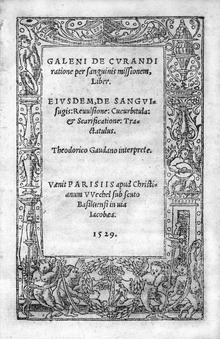

This New Learning and the Humanist movement, particularly the work of Linacre, promoted literae humaniores including Galen in the Latin scientific canon, De Naturalibus Facultatibus appearing in London in 1523.

[8] The more extreme liberal movements began to challenge the role of authority in medicine, as exemplified by Paracelsus' symbolically burning the works of Avicenna and Galen at his medical school in Basel.

Michael Servetus, using the name "Michel de Villeneuve" during his stay in France, was Vesalius' fellow student and the best Galenist at the University of Paris, according to Johann Winter von Andernach,[100] who taught both.

The Lyon edition has commentaries on breathing and blood streaming that correct the work of earlier renowned authors such as Vesalius, Caius, or Janus Cornarius.

[105][106] Another convincing case where understanding of the body was extended beyond where Galen had left it came from these demonstrations of the nature of human circulation and the subsequent work of Andrea Cesalpino, Fabricio of Acquapendente, and William Harvey.