Jack the Giant Killer

Jack and his tale are rarely referenced in English literature prior to the eighteenth century (there is an allusion to Jack the Giant Killer in William Shakespeare's King Lear, where in Act 3, one character, Edgar, in his feigned madness, cries, "Fie, foh, and fum,/ I smell the blood of a British man").

The tale is set during the reign of King Arthur and tells of a young Cornish farmer's son named Jack who is not only strong but so clever he easily confounds the learned with his penetrating wit.

A man-eating giant named Blunderbore vows vengeance for Cormoran's death and carries Jack off to an enchanted castle.

In gratitude for having spared his castle, the three-headed giant gives Jack a magic sword, a cap of knowledge, a cloak of invisibility, and shoes of swiftness.

Growing weary of the festivities, Jack sallies forth for more adventures and meets an elderly man who directs him to an enchanted castle belonging to the giant Galligantus (Galligantua, in the Joseph Jacobs version).

The giant holds captive many knights and ladies and a Duke's daughter who has been transformed into a white doe through the power of a sorcerer.

According to the Opies, Jack's magical accessories – the cap of knowledge, the cloak of invisibility, the magic sword, and the shoes of swiftness – could have been borrowed from the tale of Tom Thumb or from Norse mythology, however older analogues in British Celtic lore such as Y Mabinogi and the tales of Gwyn ap Nudd, cognate with the Irish Fionn mac Cumhaill, suggest that these represent attributes of the earlier Celtic gods such as the shoes associated with Welsh Lleu Llaw Gyffes of the Fourth Branch, Arthur's invincible sword Caledfwlch and his Mantle of Invisibility Gwenn one of the Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain mentioned in two of the branches; or the similar cloak of Caswallawn in the Second Branch.

[2][3] Another parallel is the Greek demigod Perseus, who was given a magic sword, the winged sandals of Hermes and the 'cap of darkness' (borrowed from Hades) to slay the gorgon Medusa.

King Arthur's encounter with the giant of St Michael's Mount – or Mont Saint-Michel in Brittany[5] – was related by Geoffrey of Monmouth in Historia Regum Britanniae in 1136, and published by Sir Thomas Malory in 1485 in the fifth chapter of the fifth book of Le Morte d'Arthur:[3]Then came to [King Arthur] an husbandman ... and told him how there was ... a great giant which had slain, murdered and devoured much people of the country ... [Arthur journeyed to the Mount, discovered the giant roasting dead children,] ... and hailed him, saying ... [A]rise and dress thee, thou glutton, for this day shalt thou die of my hand.

And so weltering and wallowing they rolled down the hill till they came to the sea mark, and ever as they so weltered Arthur smote him with his dagger.Anthropophagic giants are mentioned in The Complaynt of Scotland in 1549, the Opies note, and, in King Lear of 1605, they indicate, Shakespeare alludes to the Fee-fi-fo-fum chant (" ... fie, foh, and fumme, / I smell the blood of a British man"), making it certain he knew a tale of "blood-sniffing giants".

Thomas Nashe also alluded to the chant in Have with You to Saffron-Walden, written nine years before King Lear;[3] the earliest version can be found in The Red Ettin of 1528.

[7] The 17th century Franco-Breton tale of Bluebeard, however, contains parallels and cognates with the contemporary insular British tale of "Jack the Giant Killer", in particular the violently misogynistic character of Bluebeard (La Barbe bleue, published 1697) is now believed to ultimately derive in part from King Mark Conomor, the 6th century continental (and probable insular) British King of Domnonée / Dumnonia, associated in later folklore with both Cormoran of St Michael's Mount and Mont Saint Michel – the blue beard (a 'Celtic' marker of masculinity) is indicative of his otherworldly nature.

[8] Bottigheimer notes that in the southern Appalachians of the United States, Jack became a generic hero of tales usually adapted from the Brothers Grimm.

[9] John Matthews writes in Taliesin: Shamanism and the Bardic Mysteries in Britain and Ireland (1992) that giants are very common throughout British folklore, and often represent the "original" inhabitants, ancestors, or gods of the island before the coming of "civilised man", their gigantic stature reflecting their "otherworldly" nature.

[11] Giants figure prominently in Cornish, Breton and Welsh folklore, and in common with many animist belief systems, they represent the force of nature.

Among the rest was one detestable monster, named Goëmagot [Gogmagog], in stature twelve cubits [6.5 m], and of such prodigious strength that at one shake he pulled up an oak as if it had been a hazel wand.

On a certain day, when Brutus (founder of Britain and Corineus' overlord) was holding a solemn festival to the gods, in the port where they at first landed, this giant with twenty more of his companions came in upon the Britons, among whom he made a dreadful slaughter.

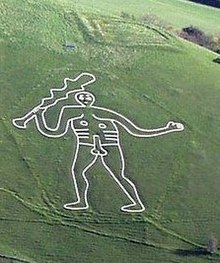

In the early seventeenth century, Richard Carew reported a carved chalk figure of a giant at the site in the first book of The Survey of Cornwall: Againe, the activitie of Devon and Cornishmen, in this facultie of wrastling, beyond those of other Shires, dooth seeme to derive them a speciall pedigree, from that graund wrastler Corineus.

Moreover, upon the Hawe at Plymmouth, there is cut out in the ground, the pourtrayture of two men, the one bigger, the other lesser, with Clubbes in their hands, (whom they terme Gog-Magog) and (as I have learned) it is renewed by order of the Townesmen, when cause requireth, which should inferre the same to bee a monument of some moment.

And lastly the place, having a steepe cliffe adjoyning, affordeth an oportunitie to the fact.Cormoran (sometimes Cormilan, Cormelian, Gormillan, or Gourmaillon) is the first giant slain by Jack.

According to Cornish legend, the couple were responsible for its construction by carrying granite from the West Penwith Moors to the current location of the Mount.

Trecobben, the giant of Trencrom Hill (near St Ives), accidentally killed Cormelian when he threw a hammer over to the Mount for Cormoran's use.

In the version of "Jack the Giant Killer" recorded by Joseph Jacobs, Blunderbore lives in Penwith, where he kidnaps three lords and ladies, planning to eat the men and make the women his wives.

Galligantus is a giant who holds captive many knights and ladies and a Duke's daughter who has been transformed into a white doe through the power of a sorcerer.

In 1962, United Artists released a middle-budget film produced by Edward Small and directed by Nathan H. Juran called Jack the Giant Killer.

The film Jack the Giant Slayer, directed by Bryan Singer and starring Nicholas Hoult was produced by Legendary Pictures and was released on 1 March 2013.