Gallo-Roman religion

Mother goddesses, who were probably fertility deities, retained their importance in Gallo-Roman religion; their cults were spread throughout Gaul.

[2] Minerva was never viewed as a water deity, however her wisdom connotations lent her some worship as a goddess of medicine.

Other healing deities worshipped by the Gauls, Glanis and the Glanicae, were merged with the Roman goddess Valetudo.

Although Mars was a war god in the Roman pantheon, he acquired connotations as a medical deity in Gallo-Roman religion.

Gallo-Roman artwork often depicts the Celtic god Cernunnos, an antlered deity frequently portrayed sitting cross-legged.

Drusus, the son of Emperor Tiberius, established a cult center near Lyon and local Roman magistrates supervised religious functions.

Gallo-Roman temples were constructed with imperishable materials such as tiles or stone; they often featured Romanized artistic embellishments such as painted wall plaster or columns.

Romanization led to the construction of more temples and the redesign of preexisting sites to more closely resemble Greco-Roman architecture.

The newer temples often retained the original layout and shape of the Celtic structures, however, their building materials and physical appearance changed to better resemble Roman architecture.

Similarities between Gallo-Roman and Celtic architecture possibly made the new religion more palatable for the local populace.

These altars contained iconography depicting religious practices such as ritual sacrifices or sacrificial equipment.

Individuals who could afford the higher quality stone utilized their wealth to create a more permanent marker of their piety contrasted with the less extravagant votive offerings.

This practice possibly continued during Roman rule; weapon despots have been unearthed in Gallo-Roman temples.

Roman policies may not have affected the rates of human sacrifice in Gaul; the practice may have already dissipated.

These laws may have served as pro-Roman propaganda meant to illustrate the moral and cultural superiority of their society.

Pomponius Mela describes a Gallo-Roman practice in which sacrificial victims have their blood drawn as they are led to the altar, rather than a true human sacrifice.

Archaeological excavations in Belgic Gaul uncovered the ruins of a man, a woman, and a child in an ancient well.

Such evidence indicates that human sacrifice may have been practiced in Gaul, and possibly continued after the Roman occupation.

One funerary stele from Kollmoor depicts a Roman auxiliary cavalryman stamping on the head of a defeated Suebian warrior.

It is possible that headhunting had become a more accepted practice within the Roman military due to the influence of Gallic culture.

One statue found near Lezoux depicts a bearded, elderly Mercury dressed in a tunic and breeches wearing a petasos and carrying a purse and a caduceus.

This statue further portrays him holding a ram-headed serpent and accompanied by a Gallic goddess, possibly Rosmerta.

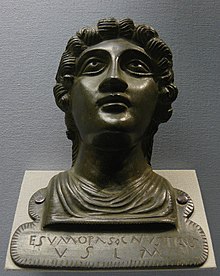

One bronze statuette from Haute-Marne depicts Jupiter holding a thunderbolt in his raised right hand and a six-spoked wheel in his left.