Baldassare Galuppi

He belonged to a generation of composers, including Johann Adolph Hasse, Giovanni Battista Sammartini, and C. P. E. Bach, whose works are emblematic of the prevailing galant music that developed in Europe throughout the 18th century.

Throughout his career Galuppi held official positions with charitable and religious institutions in Venice, the most prestigious of which was maestro di cappella at the Doge's chapel, St Mark's Basilica.

Although there is no documentation, oral tradition as related to Francesco Caffi in the nineteenth century says that the young Galuppi was trained in composition and harpsichord by Antonio Lotti, the chief organist at St Mark's Basilica.

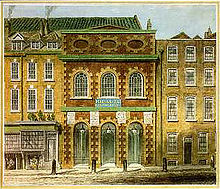

On his return to Venice in 1728, he produced a second opera, Gl'odi delusi dal sangue, written in collaboration with another Lotti pupil, Giovanni Battista Pescetti; it was well received when it was presented at the Teatro San Angelo.

[1] In 1740, Galuppi was appointed "maestro di coro" at the Ospedale dei Mendicanti in Venice, where his duties ranged from teaching and conducting to composing liturgical music and oratorios.

Of the 11 operas under his direction, at least three are known to have been his own compositions, Penelope, Scipione in Cartagine and Sirbace; a fourth was presented shortly after he left London to return to Venice.

Burney wrote, "He now copied the hasty, light and flimsy style which reigned in Italy at this time, and which Handel's solidity and science had taught the English to despise.

[1] Full-length comic operas from Naples and Rome were becoming fashionable; Galuppi adapted three of them for Venetian audiences in 1744, and the following year composed one of his own, La forza d'amore, which was only a mild success.

Of the British premiere of Il filosofo di campagna in 1761 Burney wrote, "This burletta surpassed in musical merit all the comic operas that were performed in England, till the Buona Figliuola.

He persuaded the Basilica authorities, the Procurators, to be more flexible in payments to singers, allowing him to attract performers with first-rate voices such as Gaetano Guadagni and Gasparo Pacchiarotti.

[5] Early in 1764 Catherine the Great of Russia made it known through diplomatic channels that she wished Galuppi to come to Saint Petersburg as her court composer and conductor.

There were prolonged negotiations between Russia and the Venetian authorities before the Senate of Venice agreed to release Galuppi for a three-year engagement at the Russian court.

The contract required him to "compose and produce operas, ballets and cantatas for ceremonial banquets", at a salary of 4,000 rubles and the provision of accommodation and a carriage.

[13] Galuppi was reluctant, but Venetian officials assured him that his post and salary as maestro di cappella at St. Mark's were secure until 1768 as long as he supplied a Gloria and a Credo for the Basilica's Christmas mass each year.

[14] Galuppi took pride in his prestigious appointments; the title page of his 1766 Christmas mass for St Mark's describes him as: "First Master and Director of all the Music for Her Imperial Majesty the Empress of all the Russias, etc.

[1] On his return to Venice, Galuppi resumed his duties at St Mark's and successfully applied for reappointment at the Incurabili, holding the post until 1776, when financial constraints obliged all the ospedali to cut back their musical activities.

[9] Galuppi's contemporary Esteban de Arteaga wrote approvingly that the composer was able to "illumine the personalities of the characters and the situations in which they find themselves by selecting the most appropriate type of voice and style of singing".

[25] Hitherto acts had ended in short choruses or ensembles, but the elaborate and substantial finales introduced by Galuppi and his librettist set the pattern for Haydn and Mozart.

[n 5] Galuppi's music for his comic operas is described by Luisi as "largely syllabic … designed to enhance the intelligibility of the text … without impairing the fluidity of the melodic lines.

[5] It was then the custom to incorporate into new church music the stile antico with smooth vocal lines in the tradition of Palestrina and a good deal of counterpoint.

However, Galuppi applied the stile antico sparingly, and when he felt constrained to write contrapuntal music for the choir he would balance it with a bright modern style for the orchestral accompaniment.

[5] His masses and psalm settings for St Mark's exploit all the resources available to a modern composer in the mid-18th century,[5] with choir supported by an orchestra of strings and some or all of flutes, oboes, bassoons, horns, trumpets, and organ.

[12] In his tutti choral writing, Galuppi generally leaned toward syllabic settings, reserving the technically demanding melismatic passages for soloists.

"[1] Marina Ritzarev comments that the Italian Vincenzo Manfredini was Galuppi's predecessor as Russian court composer, and may have paved the way for his successor's innovations.

Hillers Wöchentliche Nachrichten in 1772 made this mention of Galuppi's reputation in Saint Petersburg: "Chamber concerts were held every Wednesday in the antechamber of the imperial apartments, in order to enjoy the special style and fiery accuracy of the clavier playing of this great artist; thus did the virtuoso earn the overall approval of the court.

[37] Felix Raabe mentions the round number of 125 "sonatas, toccatas, divertimenti and etudes" for keyboard, based on Fausto Torrefranca's 1909 thematic catalogue of Galuppi's cembalo works.

[38] However, given some of the outrageous assertions on this topic that Torrefranca makes elsewhere (such as that the classical sonata form was created by Italian keyboard composers) the accuracy of this figure must be accepted only cautiously.

Innovations such as the chromatically raised 5th that Burney singled out in Galuppi's arias of the 1740s appear, and many harmonic features of the late-classical period are foreshadowed, such as the final deceptive cadence in which an augmented sixth chord is substituted before the ultimate resolution.

Choral works put on CD include the 1766 Messa per San Marco (2007),[4] a cantata, L'oracolo del Vaticano, to words by Goldoni (2004),[57] and motets (2001).