Ganado, Arizona

[12] Modern understanding of the historical record left behind by the Ancestral Puebloans exhibits a massive network of villages, storehouses, and fortified structures throughout the Colorado Plateau region.

Stretching from Mesa Verde in the north, to Chaco Canyon in the east, to Keet Seel (Kitsʼiil) and Betatakin (Bitátʼahkin) and Wupatki in the west, trading routes can be traced through the Ganado region to as far south as Mexico.

Pottery fragments found through the area show a wide array of design and utility, both local and foreign to Ganado.

The largest population center in this era near Ganado, is 30 mi (50 km) to the north at Canyon de Chelly.

Between 1276 and 1299, archaeologists have recorded a period of "great drought," leading (among other causes) to the eventual end of influence of Puebloan culture and peoples on the Ganado region.

Empowered by evolutionary dry farming techniques acquired via the neighboring Puebloan peoples, the early Ganado community's main crops consisted of beans, corn, and squash.

The early Ganado Navajo, like the modern people today, were speakers of a Na-Dené Southern Athabaskan languages known as Diné bizaad (lit.

Archaeological data suggests these peoples arrived in the present day Four Corners & Colorado Plateau regions in approximately the 15th century.

A mix of oral legend and archeology suggest that singer, and warrior/ runner Jilhéél came to the Ganado area in the early 18th century.

It is believed that he traveled extensively and lived amongst the Puebloan people along the Rio Grande, and migrated with many of them to the refuge of Dinetah at the start of the Spanish invasion and occupation of modern-day Arizona and New Mexico.

Research suggests that Jilhéél contributed to the construction of fortifications to the north and south, notably in the hills east of Wide Ruins 15 mi (24 km) to the southeast of Ganado.

Oral history research suggests that he inhabited "Wide Ruins, (meaning the Ancestral Puebloan site) and, a few miles north up Wide Ruins Wash, at" the citadel of "Kin Naazinii (Upstanding House)"; if not contributed to its construction – with the help of elder Daalgai – "a Navajo fortified 'pueblito' that archaeologists date at 1720–1805 (NLC, site S-MLC-UP-L; Bannister and others 1966:8; Navajo Nation 1967:263, 271, 285; Gilpin 1996)."

"Some of his attributes may reflect late pre-" Hispanic "iconography (big feet, for example, a common petroglyph motif).

These pre-" Hispanic " associations of Jilhéél, together with the idea that Wide Ruins was some kind of 'boundary' place between Hopi and Zuni zones ..., makes one wonder if the north-south travel corridor through Wide Ruins to Canyon de Chelly could have been a late 'everyone's land' as conceptualized by LaBlanc (1999:70, 333) between settlement clusters" much older.

[15] "The north-south corridor that Jilhéél stalked encompasses a string of places with names that came from incidents of raiding and warfare before the Fort Sumner captivity.

The place names, from south to north, are Anaaʼ Hajiina (Where the Enemy Came Up) north of Chambers; Dzilgha Adahjééʼ (Where the White Mountain Apaches Ran Down or Hilltop Descent), near Ganado", and the modern day location of Ganado Mucho's burial site; "and Dzilgha Haaskai (White Mountain Apaches Went Up, or Hilltop Ascent) near Chinle, Arizona (see Map 1).

As Roman Catholicism spread, by the 1629, "the mission of San Bernardino was established at Awátobi by a party of four Franciscans headed by Father Francisco de Porras",[16] as the Hopi villages were architecturally accommodating as built up population centers.

[17] One Navajo elder said of the Long Walk: By slow stages we traveled eastward by present Gallup and Chusbbito, Bear Spring, which is now called Fort Wingate.

[16] During the Long Walk, Diné Chief totsohnii Hastiin (pronounced Toe-so-knee haaus-teen)(Navajo for Man of the big water Clan), famously known as Ganado Mucho (1809–1893), along with other leaders targeted by the United States (such as Manuelito) fled to the haven of the Grand Canyon.

This maneuver protected the Navajo residents of Ganado's wealth, held in their livestock, from United States confiscation by Kit Carson.

He addressed directly the New Mexican Superintendent of Indian Affairs – A. Baldwin Norton – and condemned the conditions at Bosque Redondo.

These trading posts were established as a service to the Navajo people after the formation of the Fort Defiance Indian reservation, as a means to provide goods not locally available.

The family added onto the current adobe building which would become the famous Hubbell home, which hosted such guests as Theodore Roosevelt.

The Hubbell garden contained Virginia creeper, a lawn, as well as native wild and yellow roses, lilac and yucca.

Hubbell, his wife, three of his children, a daughter-in-law, and a granddaughter are buried on the cone-shaped hill northwest of the trading post.

Agricultural parcels are managed by a local board of Farming advocates, and the surrounding ranches are sources of organic beef and mutton.

The greater Ganado community is quite active, and throughout the winter months hold numerous Navajo religious ceremonies.

Ganado hosts satellite campuses for various collegiate level schools such as Diné College and Northern Arizona University.

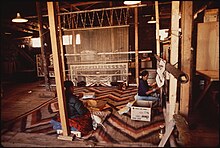

From the early 1900s demand for Ganado-produced fine rugs and blankets has grown steadily and has become world-famous since Lorenzo Hubbell began fostering the art and marketplace at his trading post.