Gandy dancer

In the Southwestern United States and Mexico, Mexican and Mexican-American track workers were colloquially traqueros.

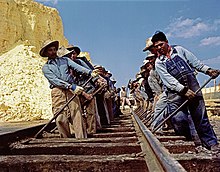

There are various theories about the derivation of the term, but most refer to the "dancing" movements of the workers using a specially manufactured five-foot (1.5 m) "lining" bar, which came to be called a "gandy", as a lever to keep the tracks in alignment.

Others have suggested that the term gandy dancer was coined to describe the movements of the workers themselves, i.e., the constant "dancing" motion of the track workers as they lunged against their tools in unison to nudge the rails, often timed by a chant; as they carried rails; or, speculatively, as they waddled like ganders while running on the railroad ties.

Then all would take a step toward their rail and pull up and forward on their pry bars to lever the track—rails, crossties and all—over and through the ballast.

Even with repeated impacts from the work crew of eight, ten, or more, any progress made in shifting the track would not become visible until after a large number of repetitions.

The work was extremely difficult and the pay was low, but it was one of the only jobs available for southern black men and newly arriving immigrants at that time.

Many of our shareholders have never seen the country our road was built to serve; they get their impression of it and of its people, not from living contact with men, but from the impersonal ticker.

They come with golden dreams, expecting in many cases to build homes, rear families, become substantial American citizens.

Some of them swing onto the freight-trains and beat their way to the nearest town, are broke when they get there, find the labor market oversupplied, and, as likely as not, are thrown into jail as vagrants.

Many of them never find a stable anchorage again; they become hobos, vagabonds, wayfarers—migratory and intermittent workers, outcasts from society and the industrial machine, ripe for the denationalized fellowship of the I. W. W."[15] Bruere concluded, "[t]his is a small but characteristic example of a vast system of human exploitation that has been developed by the powerful suction of our headlong industrial expansion..."[15] Black historian and journalist Thomas Fleming began his career as a bellhop and then spent five years as a cook for the Southern Pacific Railroad.

[16] During the early 1940s when the U.S. was involved in the fighting of World War II, the days of Rosie the Riveter, a few women worked as gandy dancers.

A 1988 article in The Valley Gazette carried the story of several local women who had worked on the Reading Railroad in Tamaqua, Pennsylvania as gandy dancers.

In the story, "Eddie Parker", about 17 or 18 years old and characterized as the all-American type, takes on a job as a worker in a railway section crew.

[22] In 1939 John Lomax recorded a number of railroad songs which contain an example of an "unloading steel rails" call; it is available at the American Memory site.

His father, a section foreman in Meridian, Mississippi, brought his son with him to work as a water boy where he would have been exposed to their musical chants.

[24][25] Anne Kimzey of the Alabama Center For Traditional Culture writes: "All-black gandy dancer crews used songs and chants as tools to help accomplish specific tasks and to send coded messages to each other so as not to be understood by the foreman and others.

USC-Columbia has a vintage gandy dancer video which demonstrates the singing, dancing-like rhythm, lining tool, and a very large crew.

[26] In 1994, folklorist Maggie Holtzberg, working as a folklore fieldworker to document traditional folk music in Alabama, produced a documentary film Gandy Dancers.

In this familiar environment the men quickly began to remember the old calls, and especially so when a train passed by blowing its whistle.

Holtzberg recalls the words of John Cole, at 82 the oldest of the men: The film was completed in 1994 and is available at the Folkstreams website.

[29] The caller simultaneously motivated and entertained the men and set the timing through work songs that derived distantly from call and response traditions brought from Africa and sea shanties, and more recently from cotton-chopping songs, blues, and African-American church music.

Then with each "huh" grunt the men throw their weight forward on their gandy to slowly bring the rail back into alignment.

Like lining calls, they also serve to mock one's superiors, vent anger and frustration, relieve boredom, and to boost spirits by poking fun or boasting.

Col. Bernard Lentz, who was the base commander at the Fort, approached Duckworth and asked where he developed his unique chant.

Singer/political activist Bruce "Utah" Phillips, in Moose Turd Pie, told a tall tale of working as a gandy dancer in the American southwest.

[36][deprecated source] In the 2005 point-and-click adventure game, Last Train to Blue Moon Canyon, a series of achievable titles could be obtained by performing various actions.