Sea shanty

From Latin cantare via French chanter,[1] the word shanty emerged in the mid-19th century in reference to an appreciably distinct genre of work song, developed especially on merchant vessels, that had come to prominence in the decades prior to the American Civil War.

[6] Narrating a voyage in a clipper ship from Bombay to New York City in the early 1860s, Clark wrote, "The anchor came to the bow with the chanty of 'Oh, Riley, Oh,' and 'Carry me Long,' and the tug walked us toward the wharf at Brooklyn.

Singing, or chanting as it is called, is an invariable accompaniment to working in cotton, and many of the screw-gangs have an endless collection of songs, rough and uncouth, both in words and melody, but answering well the purposes of making all pull together, and enlivening the heavy toil.

[10]According to research published in the journal American Speech, Schreffler argues that chanty may have been a back derivation from chanty-man, which, further, initially carried the connotation of a singing stevedore (as in Nordhoff's account, above).

The historical record shows shanty (and its variant spellings) gaining currency only in the late nineteenth century; the same repertoire was earlier referred to as "song", "chant", or "chaunt".

[16] American shanty-collector Joanna Colcord made great use of Terry's first book (corresponding with the author, and reprinting some of his material), and she, too, deemed it sensible to adopt the "sh" spelling for her 1924 collection.

Terry and Colcord's works were followed by numerous shanty collections and scores that also chose to use the "Sh" spelling,[18] whereas others remained insistent that "ch" be retained to preserve what they believed to be the etymological origins of the term.

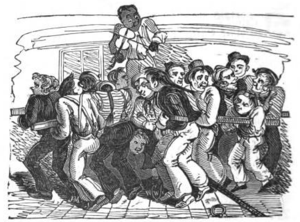

It requires, however, some dexterity and address to manage the handspec to the greatest advantage; and to perform this the sailors must all rise at once upon the windlass, and, fixing their bars therein, give a sudden jerk at the same instant, in which movement they are regulated by a sort of song or howl pronounced by one of their number.

The same dictionary noted that French sailors said just that, and gave some indication what an English windlass chant may have been like: UN, deux, troi, an exclamation, or song, used by seamen when hauling the bowlines, the greatest effort being made at the last word.

Although other work-chants were evidently too variable, non-descript, or incidental to receive titles, "Cheer'ly Man" appears referred to by name several times in the early part of the century, and it lived on alongside later-styled shanties to be remembered even by sailors recorded by James Madison Carpenter in the 1920s.

The Royal Navy banned singing during work—it was thought the noise would make it harder for the crew to hear commands—though capstan work was accompanied by the bosun's pipe,[34] or else by fife and drum or fiddle.

[37] One of the earliest references to shanty-like songs that has been discovered was made by an anonymous "steerage passenger" in a log of a voyage of an East India Company ship, entitled The Quid (1832).

For example, an observer in Martinique in 1806 wrote, "The negroes have a different air and words for every kind of labour; sometimes they sing, and their motions, even while cultivating the ground, keep time to the music.

Thus while European sailors had learned to put short chants to use for certain kinds of labor, the paradigm of a comprehensive system of developed work songs for most tasks may have been contributed by the direct involvement of or through the imitation of African-Americans.

[54] An early article to offer an opinion on the origin of shanties (though not calling them by that name), appearing in Oberlin College's student paper in 1858, drew a comparison between Africans' singing and sailor work songs.

It seems like the dirge of national degradation, the wail of a race, stricken and crushed, familiar with tyranny, submission and unrequited labor ... And here I cannot help noticing the similarity existing between the working chorus of the sailors and the dirge-like negro melody, to which my attention was specially directed by an incident I witnessed or rather heard.

[78] The English poet John Masefield, following in the footsteps of peers like Rudyard Kipling,[79] seized upon shanties as a nostalgic literary device, and included them along with much older, non-shanty sea songs in his 1906 collection A Sailor's Garland.

[90] Sharp responds to Bullen's claims of African-American origins by ceding that many shanties were influenced through the singing of Black shantymen[91]—a position that assumes English folk song was the core of the tradition by default.

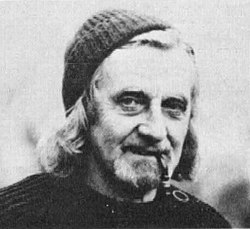

James Madison Carpenter, made hundreds of recordings of shanties from singers in Britain, Ireland, and the north-eastern U.S. in the late 1920s,[100] allowing him to make observation from an extensive set of field data.

[115] By 1928, commercial recordings of shanties, performed in the manner of classical concert singing, had been released on HMV, Vocalion, Parlophone, Edison, Aco, and Columbia labels;[116] many were realizations of scores from Terry's collection.

He was generally mysterious about the sources of his shanty arrangements; he obviously referred to collections by editors like Sharp, Colcord, and Doerflinger, however it is often unclear when and whether his versions were based in field experience or his private invention.

Lloyd's album The Singing Sailor (1955)[118] with Ewan MacColl was an early milestone, which made an impression on Stan Hugill when he was preparing his 1961 collection,[119] particularly as the performance style it embodied was considered more appropriate than that of earlier commercial recordings.

This is evidenced in the popular Folk music fake book Rise Up Singing, which includes such shanties as "Blow the Man Down", "What Shall We Do with a Drunken Sailor", and "Bound for South Australia".

For example, Bruce Springsteen's "Pay Me My Money Down" derives from the interpretation by the Folk group The Weavers, who in turn found it among the collected shanties once traditionally performed by residents of the Georgia Sea Islands.

A well-known early example, though not strictly speaking a reference to a shanty, is the song "Fifteen men on the dead man's chest", which was invented by Robert Louis Stevenson for his novel Treasure Island (1883).

A notable instance where many non-maritime music performers tackled the traditional maritime repertoire stems from the actor Johnny Depp's reported interest in shanties that developed while filming Pirates of the Caribbean.

[citation needed] Another newly composed song by folk singer Steve Goodman, "Lincoln Park Pirates", uses the phrase, "Way, hey, tow 'em away", imitating shanty choruses while at the same time anachronistically evoking the "piracy" in its subject.

[citation needed] The theme song for the television show SpongeBob SquarePants has a shanty-like call and response structure and begins with a melodic phrase that matches the traditional "Blow the Man Down", presumably because the character "lives in a pineapple under the sea.

[citation needed] English composer Michael Maybrick (alias Stephen Adams) sold a hundred thousand copies of an 1876 song Nancy Lee in Seafaring style, with lyrics by Frederick Weatherly concerning an archetypal sailors wife.

The song evoked an 1882 response Susie Bell from Australian composer Frederick Augustus Packer in the far flung British colony at Port Arthur, South Australia.