Southern question

The historical reasons for the first southern emigration in the second half of the 19th century are to be found in widespread literature both in the crisis of the countryside and grain, and in the situation of economic impoverishment affecting the south in the aftermath of unification, when industrial investments were concentrated in the northwest,[3] as well as in other factors.

In the other, the paternalist administrations of Spain and the Bourbons had created nothing: the bourgeoisie did not exist, agriculture was primitive and not even sufficient to satisfy the local market; there were no roads, no ports, no exploitation of the few waters that the region possessed because of its peculiar conformation.

According to Denis Mack Smith's exposition in his work History of Italy from 1861 to 1998, starting in 1850, Cavour's Piedmont was led by a liberal elite that marked a radical acceleration, with the declared aim of confronting the major European powers.

Nitti assessed that the system adopted by the Bourbons was due to a lack of vision, a refusal to look to the future, a principle he judged to be narrow and almost patriarchal,[16] but which at the same time guaranteed a "rough prosperity that made the life of the people less torturous than it is now".

[17] However, the causes of the southern problem must be sought in the many political and socio-economic events that the south has undergone over the centuries: In the absence of a communal period, which would have stimulated intellectual and productive energies; in the persistence of foreign monarchies, incapable of creating a modern state; in the centuries-long domination of a baronage, holder of all privileges; in the persistence of the latifundium; in the absence of a bourgeois class, creator of wealth and animator of new forms of political life; in the nefarious and corrupting Spanish domination.

Poets might write of the South as the garden of the world, the land of Sybaris and Capri, and stay-at-home politicians sometimes believed them; but in fact, most southerners lived in squalor, afflicted by drought, malaria, and earthquakes.

[23] According to Giustino Fortunato such a state of profound difference between the city of Naples and the poor provinces of the kingdom would have influenced the events of the Risorgimento in the south: "If the provinces, and not the capital, preceded the few insurrections that led to Garibaldi's landing in Reggio di Calabria, it was perhaps due in no small part to an ascetic sense of aversion to the excessive, enormous preponderance of the city of Naples, made too great, if not rich, at the cost of a small and too miserable dark kingdom....."[24] Sicily constituted a case apart: the end of the uprisings of '48 had reestablished its reunification with the rest of the peninsula, yet independence continued to be strong and would be instrumental in supporting Garibaldi's landing.

[39][40] Southernist and Lucanian senator Giustino Fortunato expressed the following opinion on the problems related to the economy of the pre-unification south: Since taxes were low, the public debt small and the currency abundant, our entire economic constitution was incapable of stimulating the production of wealth.

[49] The substitution allowed different types of precious metals to be withdrawn, generating the feeling of a real expropriation, so much so that still in 1973 Antonio Ghirelli erroneously claimed that 443 million gold lire "ended up in the North".

By way of comparison, the total financial reserve of the Bourbon state was 443.200 million liras; practically one-third of the capital of the anonymous and limited partnerships in the center-north excluding several territories not yet annexed.

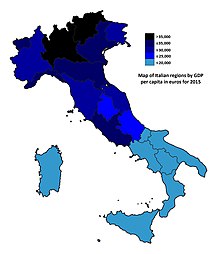

[70] According to other studies, the difference in per capita income at the time of unification would have been estimated to be 15–20% greater in the north than in the south,[71] a figure derived not only from an analysis of the number of people employed, but also from the size and competitiveness of industrial establishments.

[72] More recently, Carmine Guerriero and Guilherme de Oliveira have empirically compared the five factors identified by the main theories of the formation of economic differences between northern and southern Italy,[73] namely the democratic nature of pre-unification political institutions,[74] the inequality in the distribution of land ownership and thus in the relationship between elites and farmers,[75] the feudal backwardness of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies,[76][77] the regional endowments of raw materials and rail infrastructure,[78] and the public policies implemented by the Kingdom of Italy after unification.

Italian was spoken by an educated minority of the population, and the plebiscites that had sanctioned the unification had been conducted in a highly questionable manner, both in form and in the interference of the authorities that were supposed to supervise them, creating a false sense of consensus far superior to the real one, when many southerners would rather have expressed a need for greater autonomy.

[85] The deterioration in living conditions and the disillusionment with the expectations created by the unification led to a series of popular uprisings in Naples and in the countryside and to the phenomenon known in history as brigandage, to which the new state responded by sending in soldiers and adopting a dirigiste and authoritarian administrative model, in which local autonomies were subject to the strict control of the central government.

According to Tommaso Pedio, the rapid political transformation achieved in the south caused resentment and discontent everywhere, not only from the people and the old Bourbon class, but also from the bourgeoisie and liberals, who demanded to maintain privileges and lucrative positions from the new government.

[88] The lower classes, the only unheard voice, oppressed by hunger, upset by rising taxes and prices on primary goods, and forced into compulsory conscription, began to revolt, developing a deep resentment toward the new regime and especially toward the social strata that took advantage of political events by managing to obtain posts, jobs and new earnings.

Throughout the summer, bands of brigands, composed largely of peasants and former Bourbon soldiers, engaged in extremely violent forms of guerrilla warfare in many inland provinces, attacking and repeatedly defeating the forces of the new Kingdom of Italy.

The Lieutenant Governor of Naples, Gustavo Ponza di San Martino, who had been trying to bring about peace in the preceding months, was replaced by General Enrico Cialdini, who was given full powers by the central government to deal with the situation and suppress the revolt.

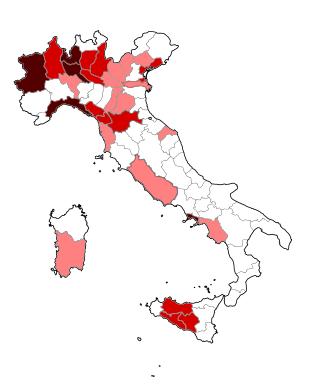

The historical reasons for the first southern emigration in the second half of the 19th century are to be found in widespread literature both in the crisis of the countryside and grain, and in the situation of economic impoverishment affecting the south in the aftermath of unification, when industrial investments were concentrated in the northwest,[3] as well as in other factors.

The aftermath of the Third War of Independence, friction over the annexation of the Papal States, and conflicting interests in Tunisia led Italy to move away from its traditional ally France and closer to Germany and Austria in the Triple Alliance.

[4] In the same vein, Luigi Einaudi pointed out how the "strong tariff barrier" of the post-unification period ensured northern industries "a monopoly of the southern market, with the consequence of impoverishing agriculture".

Two ports (Naples and Taranto) were improved, a number of roads, railways and canals were built, the construction of a large aqueduct (that of the Tavoliere delle Puglie) was undertaken, and, above all, an ambitious plan for integral reclamation was devised.

However, these were investments that met local needs only to a small extent, with a modest impact on employment and distributed according to criteria aimed at producing or consolidating consensus toward the regime on the part of the populations concerned and, at the same time, not harming the interests of the classes, notably landowners and petty-bourgeoisie, that constituted the hard core of Fascism in the south.

Attempts were made in vain to limit the influence of the latter, and so "[...] reclamation in the South came to a halt at the stage of public works, while all the turmoil that misery and permanent imbalances had caused was channeled in those years into the myth of empire".

For their part, the large companies that joined these projects and the political parties that promoted them took advantage of the uncomfortable environment in which they operated by resorting to patronage practices in hiring, without ever emphasizing productivity or the value added by business activities.

[107] As a result of the abolition of the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno, the south currently benefits from Invitalia - Agenzia nazionale per l'attrazione degli investimenti e lo sviluppo d'impresa S.p.A. and sometimes from tax breaks for hiring young people, through rebates, bonuses and deductions to encourage employment in companies located in southern Italy.

[124] According to other studies at the time of unification, the difference in per capita income was estimated to be 15–20% greater in the north than in the south,[71] a figure derived not only from an analysis of the number of people employed, but also of the size and competitive capacity of industrial establishments.

[127] Supporting this thesis are the studies conducted by Italian agricultural historian Emilio Sereni, who identified the origin of the current southern question in the economic contrast between north and south that came about as a result of the unification of Italian markets in the years immediately following the military conquest of the realm, stating: "The South became, for the new Kingdom of Italy, one of those Nebenlander (dependent territories), of which Marx speaks in regard to Ireland vis-à-vis England, where industrial capitalist development was abruptly crushed for the profit of the dominant country.

[129] The south was thus set on a process of agrarization, and the mass of labor that workers and peasant populations employed in other times in industry-related work remained unused, causing not only an industrial but also an agrarian marasmus.

In the other, the paternalist administrations of Spain and the Bourbons had created nothing: the bourgeoisie did not exist, agriculture was primitive and not even sufficient to satisfy the local market; there were no roads, no ports, no exploitation of the few waters that the region possessed due to its peculiar geological conformation.