Competitive exclusion principle

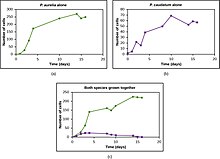

In ecology, the competitive exclusion principle,[1] sometimes referred to as Gause's law,[2] is a proposition that two species which compete for the same limited resource cannot coexist at constant population values.

[2] Based on field observations, Joseph Grinnell formulated the principle of competitive exclusion in 1904: "Two species of approximately the same food habits are not likely to remain long evenly balanced in numbers in the same region.

However, for poorly understood reasons, competitive exclusion is rarely observed in natural ecosystems, and many biological communities appear to violate Gause's law.

Spatial heterogeneity, trophic interactions, multiple resource competition, competition-colonization trade-offs, and lag may prevent exclusion (ignoring stochastic extinction over longer time-frames).

For example, a slight modification of the assumption of how growth and body size are related leads to a different conclusion, namely that, for a given ecosystem, a certain range of species may coexist while others become outcompeted.

In a project focused on the long-term impacts of the 1988 Yellowstone Fires Allen et al.[14] used stable isotopes and spatial mark-recapture data to show that Southern red-backed voles (Clethrionomys gapperi)), a specialist, are excluding deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus), a generalist, from food resources in old-growth forests.

This dynamic of establishes a pattern of ecological succession in these ecosystems, with competitive exclusion from voles shaping the amount and quality of resources deer mice can access.

In a local community, the potential members are filtered first by environmental factors such as temperature or availability of required resources and then secondly by its ability to co-exist with other resident species.

This suggests that closely related species share features that are favored by the specific environmental factors that differ among plots causing phylogenetic clustering.

While, in another study [citation needed], it's been shown that phylogenetic clustering may also be due to historical or bio-geographical factors which prevents species from leaving their ancestral ranges.

Evidence showing that the competitive exclusion principle operates in human groups has been reviewed and integrated into regality theory to explain warlike and peaceful societies.

Another recent application: in his work Historical Dynamics, Peter Turchin developed the so-called meta-ethnic frontier theory, wherein both rise and eventual fall of empires derives from geographically and or -politically colliding populations.

Summarizing its more wide-ranging predictions all in one:Asabiya is a concept from the writings of Ibn Khaldun which Turchin defines as “the capacity for collective action” of a society.

The Metaethnic Frontier theory is meant to incorporate asabiya as a key factor in predicting the dynamics of imperial agrarian societies - how they grow, shrink, and begin.

He follows by noting three ways in which the logic of multi-level selection can be relevant in understanding change in “collective solidarity”: intergroup conflict, population and resource constraints, and ethnic boundaries.

2: A larger (red) species competes for resources.

3: Red dominates in the middle for the more abundant resources. Yellow adapts to a new niche restricted to the top and bottom and avoiding competition .