Gaussian quadrature

In numerical analysis, an n-point Gaussian quadrature rule, named after Carl Friedrich Gauss,[1] is a quadrature rule constructed to yield an exact result for polynomials of degree 2n − 1 or less by a suitable choice of the nodes xi and weights wi for i = 1, ..., n. The modern formulation using orthogonal polynomials was developed by Carl Gustav Jacobi in 1826.

The quadrature rule will only be an accurate approximation to the integral above if f (x) is well-approximated by a polynomial of degree 2n − 1 or less on [−1, 1].

The Gauss–Legendre quadrature rule is not typically used for integrable functions with endpoint singularities.

where g(x) is well-approximated by a low-degree polynomial, then alternative nodes xi' and weights wi' will usually give more accurate quadrature rules.

It can be shown (see Press et al., or Stoer and Bulirsch) that the quadrature nodes xi are the roots of a polynomial belonging to a class of orthogonal polynomials (the class orthogonal with respect to a weighted inner-product).

This is a key observation for computing Gauss quadrature nodes and weights.

For the simplest integration problem stated above, i.e., f(x) is well-approximated by polynomials on

Use the two-point Gauss quadrature rule to approximate the distance in meters covered by a rocket from

The true value is given as 11061.34 m. Solution First, changing the limits of integration from

Next, get the weighting factors and function argument values from Table 1 for the two-point rule, Now we can use the Gauss quadrature formula

The integration problem can be expressed in a slightly more general way by introducing a positive weight function ω into the integrand, and allowing an interval other than [−1, 1].

If we pick the n nodes xi to be the zeros of pn, then there exist n weights wi which make the Gaussian quadrature computed integral exact for all polynomials h(x) of degree 2n − 1 or less.

But all the xi are roots of pn, so the division formula above tells us that

This proves that for any polynomial h(x) of degree 2n − 1 or less, its integral is given exactly by the Gaussian quadrature sum.

To prove the second part of the claim, consider the factored form of the polynomial pn.

This polynomial cannot change sign over the interval from a to b because all its roots there are now of even multiplicity.

To prove this, note that using Lagrange interpolation one can express r(x) in terms of

because r(x) has degree less than n and is thus fixed by the values it attains at n different points.

, the Gaussian quadrature formula involving the weights and nodes obtained from

There are many algorithms for computing the nodes xi and weights wi of Gaussian quadrature rules.

The most popular are the Golub-Welsch algorithm requiring O(n2) operations, Newton's method for solving

and leading coefficient one (i.e. monic orthogonal polynomials) satisfy the recurrence relation

The three-term recurrence relation can be written in matrix form

of the polynomials up to degree n, which are used as nodes for the Gaussian quadrature can be found by computing the eigenvalues of this matrix.

For computing the weights and nodes, it is preferable to consider the symmetric tridiagonal matrix

for some ξ in (a, b), where pn is the monic (i.e. the leading coefficient is 1) orthogonal polynomial of degree n and where

In the important special case of ω(x) = 1, we have the error estimate[6]

Stoer and Bulirsch remark that this error estimate is inconvenient in practice, since it may be difficult to estimate the order 2n derivative, and furthermore the actual error may be much less than a bound established by the derivative.

The difference between a Gauss quadrature rule and its Kronrod extension is often used as an estimate of the approximation error.

Some of the weights are: An adaptive variant of this algorithm with 2 interior nodes[9] is found in GNU Octave and MATLAB as quadl and integrate.

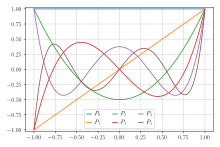

The blue curve shows the function whose definite integral on the interval [−1, 1] is to be calculated (the integrand). The trapezoidal rule approximates the function with a linear function that coincides with the integrand at the endpoints of the interval and is represented by an orange dashed line. The approximation is apparently not good, so the error is large (the trapezoidal rule gives an approximation of the integral equal to y (–1) + y (1) = –10 , while the correct value is 2 ⁄ 3 ). To obtain a more accurate result, the interval must be partitioned into many subintervals and then the composite trapezoidal rule must be used, which requires many more calculations.

The Gaussian quadrature chooses more suitable points instead, so even a linear function approximates the function better (the black dashed line). As the integrand is the third-degree polynomial y ( x ) = 7 x 3 – 8 x 2 – 3 x + 3 , the 2-point Gaussian quadrature rule even returns an exact result.