Simpson's rule

The approximate equality in the rule becomes exact if f is a polynomial up to and including 3rd degree.

Points inside the integration range are given alternating weights 4/3 and 2/3.

Simpson's 3/8 rule, also called Simpson's second rule, requires one more function evaluation inside the integration range and gives lower error bounds, but does not improve the order of the error.

Simpson's 1/3 and 3/8 rules are two special cases of closed Newton–Cotes formulas.

In naval architecture and ship stability estimation, there also exists Simpson's third rule, which has no special importance in general numerical analysis, see Simpson's rules (ship stability).

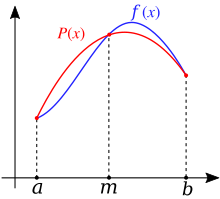

It is based upon a quadratic interpolation and is the composite Simpson's 1/3 rule evaluated for

Simpson's rule gains an extra order because the points at which the integrand is evaluated are distributed symmetrically in the interval

Since the error term is proportional to the fourth derivative of

, this shows that Simpson's rule provides exact results for any polynomial

of degree three or less, since the fourth derivative of such a polynomial is zero at all points.

Another way to see this result is to note that any interpolating cubic polynomial can be expressed as the sum of the unique interpolating quadratic polynomial plus an arbitrarily scaled cubic polynomial that vanishes at all three points in the interval, and the integral of this second term vanishes because it is odd within the interval.

terms are not equal; see Big O notation for more details.

Using another approximation (for example, the trapezoidal rule with twice as many points), it is possible to take a suitable weighted average and eliminate another error term.

The coefficients α, β and γ can be fixed by requiring that this approximation be exact for all quadratic polynomials.

(This derivation is essentially a less rigorous version of the quadratic interpolation derivation, where one saves significant calculation effort by guessing the correct functional form.)

subintervals will provide an adequate approximation to the exact integral.

By "small" we mean that the function being integrated is relatively smooth over the interval

For such a function, a smooth quadratic interpolant like the one used in Simpson's rule will give good results.

However, it is often the case that the function we are trying to integrate is not smooth over the interval.

Typically, this means that either the function is highly oscillatory or lacks derivatives at certain points.

In these cases, Simpson's rule may give very poor results.

One common way of handling this problem is by breaking up the interval

Simpson's rule is then applied to each subinterval, with the results being summed to produce an approximation for the integral over the entire interval.

corresponds with the regular Simpson's rule of the preceding section.

In practice, it is often advantageous to use subintervals of different lengths and concentrate the efforts on the places where the integrand is less well-behaved.

Thus, the 3/8 rule is about twice as accurate as the standard method, but it uses one more function value.

[5] A further generalization of this concept for interpolation with arbitrary-degree polynomials are the Newton–Cotes formulas.

Integration by Simpson's 1/3 rule can be represented as a weighted average with 2/3 of the value coming from integration by the trapezoidal rule with step h and 1/3 of the value coming from integration by the rectangle rule with step 2h.

[7] The two rules presented above differ only in the way how the first derivative at the region end is calculated.

It is possible to generate higher order Euler–Maclaurin rules by adding a difference of 3rd, 5th, and so on derivatives with coefficients, as defined by Euler–MacLaurin formula.