Ming treasure voyages

During the course of the voyages, they destroyed Chen Zuyi's pirate fleet at Palembang, captured the Sinhalese Kotte kingdom of King Alakeshvara, and defeated the forces of the Semudera pretender Sekandar in northern Sumatra.

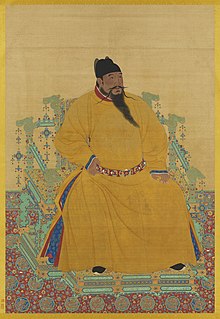

Near the end of the maritime voyages, the civil government gained the upper hand within the state bureaucracy, while the eunuchs gradually fell out of favor after the death of the Yongle Emperor and lost the authority to conduct these large-scale endeavors.

[18] The other principal officers, such as Wang Jinghong, Hou Xian, Li Xing, Zhu Liang, Zhou Man, Hong Bao, Yang Zhen, Zhang Da, and Wu Zhong, were court eunuchs employed in the civil service.

[36][53][54] After accompanying the fleet during the return journey, the foreign envoys (from Calicut, Quilon, Semudera, Aru, Malacca, and other unspecified nations) visited the Ming court to pay homage and present tribute with their local products.

[57] The Taizong Shilu records that Zheng and others went as envoys to the countries of Calicut, Malacca, Semudera, Aru, Jiayile, Java, Siam, Champa, Cochin, Abobadan, Quilon, Lambri, and Ganbali.

[69] Straight-away, their dens and hideouts we ravaged, And made captive that entire country, Bringing back to our august capital, Their women, children, families and retainers, leaving not one, Cleaning out in a single sweep those noxious pests, as if winnowing chaff from grain...

[90] The Taizong Shilu records Malacca, Java, Champa, Semudera, Aru, Cochin, Calicut, Lambri, Pahang, Kelantan, Jiayile, Hormuz, Bila, Maldives, and Sunla as stops for this voyage.

[102][103] The fleet visited Champa, Pahang, Java, Palembang, Malacca, Semudera, Lambri, Ceylon, Cochin, Calicut, Shaliwanni (possibly Cannanore), Liushan (Maladive and Laccadive Islands), Hormuz, Lasa, Aden, Mogadishu, Brava, Zhubu, and Malindi.

[108] Gong Zhen's Xiyang Fanguo Zhi records a 10 November 1421 imperial edict instructing Zheng He, Kong He (孔和), Zhu Buhua (朱卜花), and Tang Guanbao (唐觀保) to arrange the provisions for Hong Bao and others' escort of foreign envoys to their countries.

[118] On 31 January 1423, as reported in the Tarih al-Yaman fi d-daulati r-Rasuliya, the Sultan of the Rasulid issued an order to receive a Chinese delegation in the capital Ta'izz in February and goods were exchanged.

We have set eyes on barbarian regions far away hidden in a blue transparency of light vapours, while our sails, loftily unfurled like clouds, day and night continued their course with starry speed, breasting the savage waves as if we were treading a public thoroughfare.

[173] The voyages were a means to establish direct links between the Ming court and foreign tribute states, which effectively outflanked both private channels of trade and local civil officials sabotaging the prohibitions against overseas exchange.

[185] Kutcher (2020) challenges this view, as he argues that late Ming and early Qing texts reveal that critique on the voyages had to do with the excesses of eunuch power due to the corruption of the boundaries between the inner and outer court, rather than a set of ideological objections.

[186] Ray (1987) states that the cessation of the voyages happened as traders and bureaucrats, for reasons of economic self-interest and through their connections in Beijing, gradually collapsed the framework supporting both the state-controlled maritime enterprise and the strict regulation of the private commerce with prohibitive policies.

[188] The Yongle Emperor extracted funds from the national treasuries to finance his construction projects and military operations, which included the treasure voyages, while he monopolized on the trade income to ensure freedom to realize his ambitious plans.

[203] Chen (2019) states that the establishment of institutionalized tributary relations for mutual benefit, where foreign polities voluntarily cooperated in accordance to their own interests, was the fundamental way for the Chinese to attain their objectives.

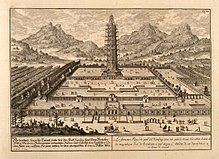

[259] The Xia Xiyang records the names of several ships—Qinghe (清和; 'pure harmony'), Huikang (惠康; 'kind repose'), Changning (長寧; 'lasting tranquility'), Anji (安濟; 'peaceful crossing'), and Qingyuan (清遠; 'pure distance')—and notes that there were also ships designated by a series number.

[140][259] Before the Ming treasure voyages, there was turmoil around the seas near the Chinese coast and distant Southeast Asian maritime regions, characterized by piracy, banditry, slave trade, and other illicit activities.

[60] The early stages of the voyages were especially characterized by highly militaristic objectives, as the Chinese stabilized the sea passages from hostile entities as well as strengthened their own position and maintained their status in the region.

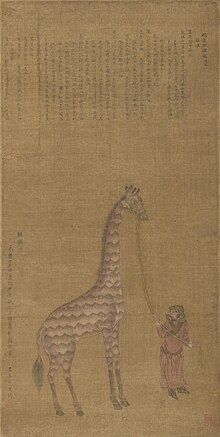

[13][270] In turn, Zheng He returned to China with many kinds of tribute goods, such as silver, spices, sandalwood, precious stones, ivory, ebony, camphor, tin, deer hides, coral, kingfisher feathers, tortoise shells, gums and resin, rhinoceros horn, sapanwood and safflower (for dyes and drugs), Indian cotton cloth, and ambergris (for perfume).

[281] The Chinese treasure fleet sailed the equatorial and subtropical waters of the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, where they were dependent on the circumstances of the annual cycle of monsoon winds.

[290] The fanhuozhang and the huozhang as well as others were recorded in the Ming Shilu, in connection to awards given to the crew for participation in the battles at Palembang and Ceylon as well as a hostile encounter between returning ships led by the eunuch Zhang Qian (張謙) and Japanese pirates—who were inflicted a heavy defeat—near Jinxiang in Zhejiang.

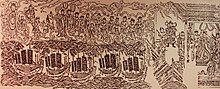

[292] The directions are expressed by compass points and distances in watches, with references to navigational techniques (such as depth sounding to avoid shallow waters) and astronomy (particularly along the north–south route of Africa where the latitude is determined by the height of constellations relative to the horizon).

In the midst of the rushing waters it happened that, when there was a hurricane, suddenly a divine lantern was seen shining at the masthead, and as soon as that miraculous light appeared the danger was appeased, so that even in the peril of capsizing one felt reassured and that there was no cause for fear.

[305] The Confucian polytheistic and this-worldly worldview, in which the moral efficacy of diverse religiosities are recognized and all people are considered to have access to heavenly principles by virtue of their reason, is expressed by religious pluralism.

1522),[324] Lu Rong's Shuyuan Zaji [菽園雜記; 'Bean Garden Miscellany'] (1475),[325] Yan Congjian's Shuyu Zhouzilu [殊域周咨錄; 'Record of Despatches Concerning the Different Countries'] (1520),[325] and Gu Qiyuan's Kezuo Zhuiyu [客座贅語; 'Boring Talks for My Guests'] (ca.

[337] Suryadinata (2005) remarks that Southeast Asian sources also provide information about the voyages, but that their reliability should be scrutinized as these local histories can be intertwined with legends but still remain relevant in the collective memories of the people concerned.

[343] The Qurrat al-Uyun fi Akhbar al-Yaman al-Maimun (1461–1537) describes an encounter between Rasulid Sultan al-Nasir Ahmad (r. 1400–1424) and Chinese envoys, providing an example of a ruler who willingly accedes to the requested protocol of the tributary relationship in the unique perspective of a non-Chinese party.

[346] In the late 16th century, Juan González de Mendoza wrote that "it is plainly seene that [the Chinese] did come with the shipping unto the Indies, having conquered al that is from China, unto the farthest part thereof.

[351][352] Although the present-day popular narrative may emphasize the peaceful nature of the voyages, especially in terms of the absence of territorial conquest and colonial subjugation, it overlooks the heavy militarization of the Chinese treasure fleet to exercise power projection and thereby promote its interests.