Wang Zhen (inventor)

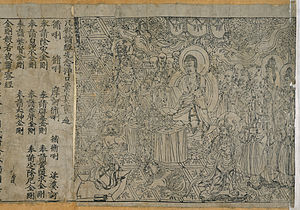

His illustrated agricultural treatise was also one of the most advanced of its day, covering a wide range of equipment and technologies available in the late 13th and early 14th century.

[1] Although the title describes the main focus of the work, it incorporated much more information on a wide variety of subjects that was not limited to the scope of agriculture.

Wang's Nong Shu of 1313 was a very important medieval treatise outlining the application and use of the various Chinese sciences, technologies, and agricultural practices.

[3] Hence, a book such as the Nong Shu could help rural farmers maximize efficiency of producing yields and they could learn how to use various agricultural tools to aid their daily lives.

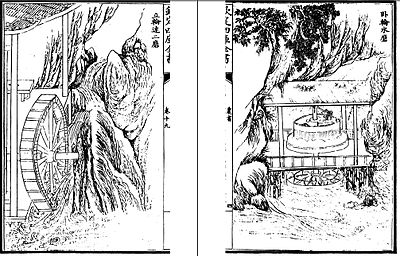

[4] The Chinese, during the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220), were the first to apply hydraulic power (i.e. a waterwheel) in working the inflatable bellows of the blast furnace in creating cast iron.

In the 5th century text of the Wu Chang Ji, its author Pi Ling wrote that a planned, artificial lake had been constructed in the Yuan-Jia reign period (424–429) for the sole purpose of powering water wheels aiding the smelting and casting processes of the Chinese iron industry.

A place beside a rushing torrent is selected, and a vertical shaft is set up in a framework with two horizontal wheels so that the lower one is rotated by the force of the water.

Then all as one, following the turning (of the driving wheel), the connecting-rod attached to the eccentric lug pushes and pulls the rocking roller, the levers to left and right of which assure the transmission of the motion to the piston-rod.

At the end of the wooden (piston-)rod, about 3 ft long, which comes out from the front of the bellows, there is set up right a curved piece of wood shaped like the crescent of the new moon, and (all) this is suspended from above by a rope like those of a swing.

Then in accordance with the turning of the (vertical) water-wheel, the lug fixed on the driving-shaft automatically presses upon and pushes the curved board (attached to the piston-rod), which correspondingly moves back (lit.

This is also very convenient and quick...[9]According to Joseph Needham, Wang Zhen's blowing engine is one of "the two machines of the Middle Ages which lie most directly in the line of ancestry of the steam-engine and the locomotive" along with Al-Jazari's slot-rod force pump a century earlier.

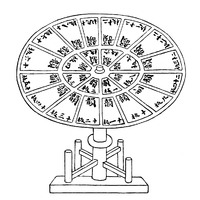

[2] His main contribution was improving the speed of typesetting with simple mechanical devices, along with the complex, systematic arrangement of wooden movable types.

[12] Wang's wooden movable type was used to print the local gazetteer paper of Jingde City, which incorporated the use of 60,000 written characters organized on revolving tables.

[12] Following in the footsteps of Wang, in 1322 the magistrate of Fenghua, Zhejiang province, named Ma Chengde, printed Confucian classics with movable type of 100,000 written characters on needed revolving tables.

[19] There were many books from a wide variety of subjects published in wooden movable type during the Ming period, including novels, art, science and technology, family registers, and local gazettes.

[19] The creation of movable type writing fonts became a wise enterprise of investment, since they were commonly pawned, sold, or presented as gifts during the Qing period.

[19] In the sphere of the imperial court, the official Jin Jian (d. 1794) was placed in charge of printing at the Wuying Palace, where the Yongzheng Emperor had 253,000 wooden movable type characters crafted in the year of 1733.

[23] Amongst the various contemporary agricultural practices mentioned in the Nong Shu, Wang listed and described the use of ploughing, sowing, irrigation, cultivation of mulberries, etc.