William Tecumseh Sherman

Sherman accepted the surrender of all the Confederate armies in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida in April 1865, but the terms that he negotiated were considered too generous by U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who ordered General Grant to modify them.

Along with fellow Lieutenants Henry Halleck and Edward Ord, Sherman embarked from New York City on the 198-day journey around Cape Horn, aboard the converted sloop USS Lexington.

[33] In his memoirs, Sherman relates a hike with Halleck to the summit of Corcovado, overlooking Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, in order to examine the city's aqueduct design.

"[53] The failure of Page, Bacon & Co. triggered a panic surrounding the "Black Friday" of February 23, 1855, leading to the closure of several of San Francisco's principal banks and many other businesses.

Boyd later recalled witnessing that, when news of South Carolina's secession from the United States reached them at the Seminary, "Sherman burst out crying, and began, in his nervous way, pacing the floor and deprecating the step which he feared might bring destruction on the whole country.

Instead of complying, he resigned his position as superintendent, declaring to the governor of Louisiana that "on no earthly account will I do any act or think any thought hostile to or in defiance of the old Government of the United States.

[83] Having succeeded Anderson at Louisville, Sherman now had principal military responsibility for Kentucky, a border state in which the Confederates held Columbus and Bowling Green, and were also present near the Cumberland Gap.

[b] He became exceedingly pessimistic about the outlook for his command and he complained frequently to Washington about shortages, while providing exaggerated estimates of the strength of the rebel forces and requesting inordinate numbers of reinforcements.

Although Sherman was technically the senior officer, he wrote to Grant, "I feel anxious about you as I know the great facilities [the Confederates] have of concentration by means of the River and R[ail] Road, but [I] have faith in you—Command me in any way.

[106] Grant, who was on poor terms with McClernand, regarded this as a politically motivated distraction from the efforts to take Vicksburg, but Sherman had targeted Arkansas Post independently and considered the operation worthwhile.

[109] The failure of the first phase of the campaign against Vicksburg led Grant to formulate an unorthodox new strategy, which called for the invading Union army to leave its supply train and subsist by foraging.

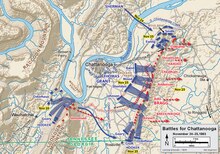

This frontal assault was intended as a diversion, but it unexpectedly succeeded in capturing the enemy's entrenchments and routing the Confederate Army of Tennessee, bringing the Union's Chattanooga campaign to a successful completion.

[127] As Grant took overall command of the armies of the United States, Sherman wrote to him outlining his strategy to bring the war to an end: "If you can whip Lee and I can march to the Atlantic I think ol' Uncle Abe [Lincoln] will give us twenty days leave to see the young folks.

[129] He conducted a series of flanking maneuvers through rugged terrain against Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee, attempting a direct assault only at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain.

[157] Having defeated the Confederate forces under Johnston at Bentonville, Sherman proceeded to rendezvous at Goldsboro with the Union troops that awaited him there after the captures of the coastal cities of New Bern and Wilmington.

At the insistence of Johnston, Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge, Sherman conditionally agreed to generous terms that dealt with both military and political issues.

[163] Sherman believed that the terms that he had agreed to were consistent with the views that Lincoln had expressed at City Point, and that they offered the best way to prevent Johnston from ordering his men to go into the wilderness and conduct a destructive guerrilla campaign.

The assassination of Lincoln had caused the political climate in Washington to turn against the prospect of a rapid reconciliation with the defeated Confederates, and the Johnson administration rejected Sherman's terms.

[182][183] According to historian Eric Foner, "the 'Colloquy' between Sherman, Stanton, and the black leaders offered a rare lens through which the experience of slavery and the aspirations that would help to shape Reconstruction came into sharp focus.

The influential 20th-century British military historian and theorist B. H. Liddell Hart ranked Sherman as "the first modern general" and one of the most important strategists in the annals of war, along with Scipio Africanus, Belisarius, Napoleon Bonaparte, T. E. Lawrence, and Erwin Rommel.

[195] Liddell Hart's views on the historical significance of Sherman have since been discussed and, to varying extents, defended by subsequent military scholars such as Jay Luvaas,[196] Victor Davis Hanson,[197] and Brian Holden-Reid.

[199] Liddell Hart also declared that the study of Sherman's campaigns had contributed significantly to his own "theory of strategy and tactics in mechanized warfare", and claimed that this had in turn influenced Heinz Guderian's doctrine of Blitzkrieg and Rommel's use of tanks during the Second World War.

In his memoirs, Sherman said, "In my official report of this conflagration, I distinctly charged it to General Wade Hampton, and confess I did so pointedly, to shake the faith of his people in him, for he was in my opinion boastful, and professed to be the special champion of South Carolina.

[232] When the Medicine Lodge Treaty failed in 1868, Sherman authorized his subordinate in Missouri, Major General Philip Sheridan, to lead the winter campaign of 1868–1869, of which the Battle of Washita River was part.

Following the 1866 Fetterman Massacre, in which 81 U.S. soldiers were ambushed and killed by Native American warriors, Sherman telegraphed Grant that "we must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children".

[257] On June 19, 1879, Sherman delivered a wholly inspirational address to the graduating class of the Michigan Military Academy, in which he did not use the word hell, nor mention the horrors of war.

[285] Thomas's decision to abandon his career as a lawyer in 1878 to join the Jesuits and prepare for the Catholic priesthood caused Sherman profound distress, and he referred to it as a "great calamity".

The magazine Confederate Veteran, based in Nashville, dedicated more attention to Sherman than to any other Union general, in part to enhance the visibility of the Civil War's western theater.

[298] In the early 20th century, Sherman's role in the Civil War attracted attention from influential British military intellectuals, including Field Marshal Lord Wolseley, Maj. Gen. J. F. C. Fuller, and especially Capt.

[306] The admiration of scholars such as B. H. Liddell Hart,[307] Lloyd Lewis, Victor Davis Hanson,[308] John F. Marszalek,[309] and Brian Holden-Reid[310] for Sherman owes much to what they see as an approach to the exigencies of modern armed conflict that was both effective and principled.

Issue of 1893

Issue of 1895

1937 commemorative issue