Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868)

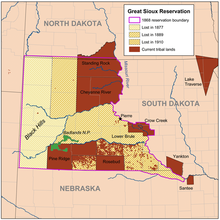

It established the Great Sioux Reservation including ownership of the Black Hills, and set aside additional lands as "unceded Indian territory" in the areas of South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska, and possibly Montana.

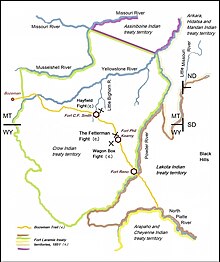

It stipulated that the government would abandon forts along the Bozeman Trail and included a number of provisions designed to encourage a transition to farming and to move the tribes "closer to the white man's way of life."

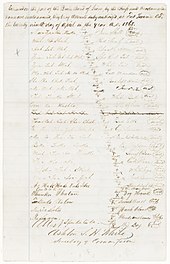

The treaty was negotiated by members of the government-appointed Indian Peace Commission and signed between April and November 1868 at and near Fort Laramie, in the Wyoming Territory, with the final signatories being Red Cloud himself and others who accompanied him.

Animosities over the agreement arose quickly, with open war breaking out again in 1876, and in 1877 the US government unilaterally annexed native land protected under the treaty.

The discovery of gold in the west, and the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad, led to substantially increased travel through the area, largely outside the 1851 Sioux territory.

This increasingly led to clashes between the tribes, settlers, and the US government, and eventually open war between the Sioux (and the Cheyenne and Arapaho refugees from the Sand Creek massacre in Colorado, 1864)[10]: 168–70 and the whites in 1866.

"[28]: 69 After losing resolve to continue the war, following defeat in the Fetterman Fight, sustained guerrilla warfare by the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho, exorbitant rates for freight through the area, and difficulty finding contractors to work the rail lines, the US Government, organized the Indian Peace Commission to negotiate an end to ongoing hostilities.

If crimes were committed by "bad men" among white settlers, the government agreed to arrest and punish the offenders, and reimburse any losses suffered by injured parties.

The tribes agreed to turn over criminals among them, any "bad men among the Indians," to the government for trial and punishment, and to reimburse any losses suffered by injured parties.

[31] If any Sioux committed "a wrong or depredation upon the person or property on any one, white, black, or Indians" the US could pay damages taken from the annuities owed the tribes.

[31] According to one source writing on article two, "What remained unstated in the treaty, but would have been obvious to Sherman and his men, is that land not placed in the reservation was to be considered United States property, and not Indian territory.

[31][45] Article 10 provided for an allotment of clothes, and food, in addition to one "good American cow" and two oxen for each lodge or family who moved to the reservation.

"[31] Article 11 included several provisions stating the tribes agreed to withdraw opposition to the construction of railroads (mentioned three times), military posts and roads, and will not attack or capture white settlers or their property.

[7]: 1002 The government agreed to reimburse the tribes for damages caused in the construction of works on the reservation, in the amount assessed by "three disinterested commissioners" appointed by the President.

[31] It guaranteed the tribes access to the area to the north and west of the Black Hills[k] as hunting grounds, "so long as the buffalo may range thereon in such numbers as to justify the chase.

"[46]: 4 As one source examined the treaty language with regard to "so long as the buffalo may range", the tribes considered this language to be a perpetual guarantee, because "they could not envision a day when buffalo would not roam the plains"; however: The concept was clear enough to the commissioners … [who] well knew that hide hunters, with Sherman's blessing, were already beginning the slaughter that would eventually drive the Indians to complete dependence on the government for their existence.

[1]Despite Sioux promises of undisturbed construction of railroads and no attacks, more than 10 surveying crew members, US Army Indian scouts and soldiers were killed in 1872[27]: 49 [47]: 11, 13–4 [48]: 61 and 1873.

[31][32]: 44 Hedren reflected on article 12 writing that the provision indicated the government "already anticipated a time when different needs would demand the abrogation of the treaty terms.

"[30]: 5 These provisions have since been controversial, because subsequent treaties amending that of 1868 did not include the required agreement of three-fourths of adult males, and so under the terms of 1868, are invalid.

[o] This article proclaims the shift of the Indian title to the land east of the summits of the Big Horn Mountains to Powder River (the combat zone of Red Cloud's War).

[55] Although the commissioners signed the document on April 29 along with the Brulé, the party broke up in May, with only two remaining at Fort Laramie to conclude talks there, before traveling up the Missouri River to gather additional signatures from tribes elsewhere.

As one writer phrased it, "the commissioners essentially cycled Sioux in and out of Fort Laramie ... seeking only the formality of the chiefs' marks and forgoing true agreement in the spirit that the Indians understood it.

"[44]: 46 William Dye, the commander at Fort Laramie was left to represent the commission, and met with Red Cloud, who was among the last to sign the treaty on November 6.

[30]: 3 [44]: 46 The government remained unwilling to negotiate the terms further, and after two days, Red Cloud is reported to have "washed his hands with the dust of the floor" and signed, formally ending the war.

[40]: 1–2 Yet others would not fully learn the terms of the agreement until 1870, when Red Cloud returned from a trip to Washington D.C.[44]: 47 The treaty overall, and in comparison with the 1851 agreement, represented a departure from earlier considerations of tribal customs, and demonstrated instead the government's "more heavy-handed position with regard to tribal nations, and ... desire to assimilate the Sioux into American property arrangements and social customs.

"[60] According to one source, "animosities over the treaty arose almost immediately" when a group of Miniconjou were informed they were no longer welcome to trade at Fort Laramie, being south of their newly established territory.

By entering the peace talks "... the government had in effect betrayed the Crows, who had willingly helped the army to hold the [Bozeman Trail] posts ...".

[64]: X Both the tribes and the government chose to ignore portions of the treaty, or to "comply only as long as conditions met their favor," and between 1869 and 1876, at least seven separate skirmishes occurred within the vicinity of Fort Laramie.

"[66]: 145 The government eventually broke the terms of the treaty following the Black Hills Gold Rush and an expedition into the area by George Armstrong Custer in 1874, and failed to prevent white settlers from moving onto tribal lands.

[60] On June 30, 1980, the US Supreme Court ruled that the government had illegally taken land in the Black Hills granted by the 1868 treaty, by unlawfully abrogating article two of the agreement during negotiations in 1876, while failing to achieve the signatures of two-thirds the adult male population required to do so.