Genetic history of Italy

Modern Italians mostly descend from the ancient peoples of Italy, including Indo-European speakers (Romans and other Latins, Falisci, Picentes,Umbrians, Samnites, Oscans, Sicels, Elymians, Messapians and Adriatic Veneti, as well as Magno-Greeks, Cisalpine Gauls and Illyric Iapygians) and pre-Indo-European speakers (Etruscans, Ligures, Rhaetians Camunni, Sicani, Nuragic peoples), as well as settlers from Phoenicia and Carthage in Sardinia and in the westernmost part of Sicily.

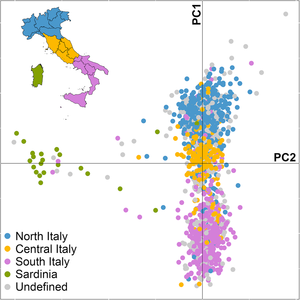

[35] Northern and Southern Italians began to diverge as early as the Late Glacial, and appear to encapsulate at a smaller scale the cline of genetic diversity observable across Europe.

From the 8th century BC, Greek colonists settled on the southern Italian coast and founded cities, forming what would be later called Magna Graecia.

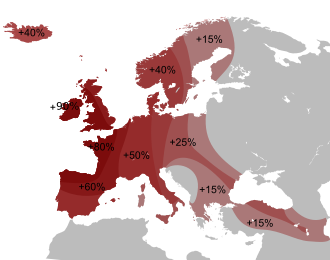

[39] With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, different populations of Germanic origin invaded Italy, the most significant being the Lombards,[40] followed five centuries later by the Normans in Sicily.

[45] This study found that the ancient DNA extracted from the Etruscan remains had some affinities with modern European populations including Germans, English people from Cornwall, and Tuscans in Italy.

[51] Their DNA was a mixture of two-thirds Copper Age ancestry (EEF + WHG; Etruscans ~66–72%, Latins ~62–75%) and one-third Steppe-related ancestry (Etruscans ~27–33%, Latins ~24–37%) (with the EEF component mainly deriving from Neolithic-era migrants to Europe from Anatolia and the WHG being local Western European hunter-gatherers, with both components, along with that from the steppe, being found in virtually all European populations).

Regarding mitochondrial DNA haplogroups, the most prevalent was largely H, followed by J and T. Uniparental marker data and autosomal DNA data from samples of Iron Age Etruscan individuals suggest that Etruria received migrations with a large ancestral Steppe component during the 2nd millennium BC, related to the spread of Indo-European languages, starting with the Bell Beaker culture, and that these migrations merged with populations of the oldest pre-Indo-European layer present since at least the Neolithic period, but it was the latter's language that survived, a situation similar to what happened in the Basque region of northern Spain.

The admixture model showed that they were 84-92% Italy Bell Beaker and 8-26% additional Yamnaya Samara (Steppe-related) ancestry, but with one individual being more similar to Iron Age populations from Scandinavia, and north-west Europe.

[55] Achilli et al. (2007) found in a modern sample of 86 individuals from Murlo, a small town in southern Tuscany, an unusually high frequency (17.5%) of supposed Near Eastern mtDNA haplogroups, while other Tuscan populations do not show the same striking feature.

[63] In 2019, in a Stanford study published in Science, two ancient samples from the Neolithic settlement of Ripabianca di Monterado in the province of Ancona, in the Marche region of Italy, were found to be Y-DNA J-L26 and J-M304.

[70][71] A study from the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore found that while Greek colonization left little significant genetic contribution, data analysis sampling 12 sites in the Italian peninsula supported a male demic diffusion model and Neolithic admixture with Mesolithic inhabitants.

The position of Volterra in central Tuscany keeps the debate about the origins of Etruscans open, although the numbers are strongly in favor of the autochthonous thesis: the low presence of J2a-M67* (2.7%) suggests contacts by sea with Anatolian people; the presence of Central European lineage G2a-L497 (7.1%) at considerable frequency would rather support a Central European origin of the Etruscans; and finally, the high incidence of European R1b lineages (R1b 50% approx., R1b-U152 24.5%) — especially of haplogroup R1b-U152 — could suggest an autochthonous origin due to a process of formation of the Etruscan civilisation from the preceding Villanovan culture, following the theories of Dionysius of Halicarnassus,[68] as already supported by archaeology, anthropology and linguistics.

[75][76][77][78] In 2019, in a Stanford study published in Science, two ancient samples from the Neolithic settlement of Ripabianca di Monterado in province of Ancona, in the Marche region of Italy, were found to be Y-DNA J-L26 and J-M304.

Nowadays it is in central and western Sicily, that Norman Y-DNA is common, with 15% to 20% of the lineages belonging to haplogroup I, this percentage drops to 8% in the eastern part of the island.

"[33] These mtDNAs by Brisighelli et al. were reported with the given results as "Mitochondrial DNA haplotypes of African origin are mainly represented by haplogroups M1 (0.3%), U6 (0.8%) and L (1.2%) for the 583 samples tested.

[94][95] A 2010 study of Jewish genealogy found that with respect to non-Jewish European groups, the populations which are most closely related to Ashkenazi Jews are modern-day Italians followed by the French and Sardinians.

The study which was focused on the mitochondrial U5b3 haplogroup discovered that this female lineage had in fact originated in Italy and around 10,000 years ago it expanded from the Peninsula towards Provence and the Balkans.

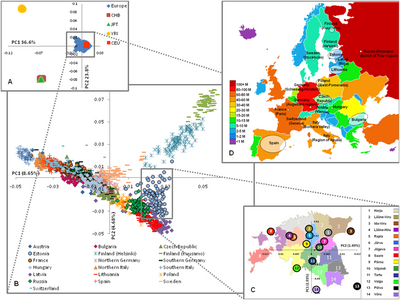

[102] López Herráez et al. (2009) typed the same samples at close to 1 million SNPs and analyzed them in a Western Eurasian context, identifying a number of subclusters.

An average admixture date of around 55 generations/1100 years ago was also calculated, "consistent with North African gene flow at the end of the Roman Empire and subsequent Arab migrations"[104] A 2012 study by Di Gaetano et al. used 1,014 Italians with wide geographical coverage.

[21]A 2013 study by Peristera Paschou et al. confirms that the Mediterranean Sea has acted as a strong barrier to gene flow through geographic isolation following initial settlements.

[17] Ancient DNA analysis reveals that Ötzi the Iceman clusters with modern Southern Europeans and closest to Italians (the orange "Europe S" dots in the plots below), especially those from the island of Sardinia.

Other Italians pull away toward Southeastern and Central Europe consistent with geography and some post-Neolithic gene flow from those areas (e.g. Italics, Greeks, Etruscans, Celts), but despite that and centuries of history, they're still very similar to their prehistoric ancestor.

The results are very interesting in light of the ancient DNA evidence that has come out in the last couple years:In addition to the pattern described in the main text, the SARD sample seemed to have played a major role as source of admixture for most of the examined populations, especially Italian ones, rather than as recipient of migratory processes.

This scenario could be interpreted as further evidence that Sardinians retain high proportions of a putative ancestral genomic background that was considerably widespread across Europe at least until the Neolithic and that has been subsequently erased or masked in most of present-day European populations.

[25]Sarno et al. (2017) concentrate on the genetic impact brought by the historical migrations around the Mediterranean on Southern Italy and Sicily, and conclude that the "results demonstrate that the genetic variability of present-day Southern Italian populations is characterized by a shared genetic continuity, extending to large portions of central and eastern Mediterranean shores", while showing that "Southern Italy appear more similar to the Greek-speaking islands of the Mediterranean Sea, reaching as far east as Cyprus, than to samples from continental Greece, suggesting a possible ancestral link which might have survived in a less admixed form in the islands", also precises how "besides a predominant Neolithic-like component, our analyses reveal significant impacts of Post-Neolithic Caucasus- and Levantine-related ancestries.

"[14] Raveane et al. (2019) discovered in a genome-wide study on modern-day Italians a contribution of Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers from the third millennium Anatolian Bronze Age, predominantly in Southern Italy.

Even more detailed structure was observed between subregional clusters, caused by geography and distance, and historical admixture possibly associated with events at the end of the Roman Empire and during subsequent periods.

[2] A 2022 genome-wide study of more than 700 individuals from the South Mediterranean area (102 from Southern Italy), combined with ancient DNA from neighbouring areas, found high affinities of South-Eastern Italians with modern Eastern Peloponnesians, and a closer affinity of ancient Greek genomes with those from specific regions of South Italy than modern Greek genomes.

The study also discovered common genetic sources shared between South Italy and Peloponnese, which can be modeled as a mixture of Anatolian Neolithic and Iranian Chalcolithic ancestries.

The biomolecular and Isotopic results suggest the Christians remained genetically distinct from the Muslim community at Segesta while following a substantially similar diet.

South/West European North/East European Caucasus

West Asian South Asian East Asian North African/Sub-Saharan African [ 100 ]