Proto-Indo-Europeans

This story, found in contemporary Indo-European folktales from Scandinavia to India, describes a blacksmith who offers his soul to a malevolent being (commonly a devil in modern versions of the tale) in exchange for the ability to weld any kind of materials together.

According to the authors, the reconstruction of this folktale to PIE implies that the Proto-Indo-Europeans had metallurgy, which in turn "suggests a plausible context for the cultural evolution of a tale about a cunning smith who attains a superhuman level of mastery over his craft".

The pioneering work of Marija Gimbutas, assisted by Colin Renfrew, at least partly addressed this problem by organizing expeditions and arranging for more academic collaboration between Western and non-Western scholars.

However, Aryan more properly applies to the Indo-Iranians, the Indo-European branch that settled parts of the Middle East and South Asia, as only Indic and Iranian languages explicitly affirm the term as a self-designation referring to the entirety of their people, whereas the same Proto-Indo-European root (*aryo-) is the basis for Greek and Germanic word forms which seem only to denote the ruling elite of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) society.

In fact, the most accessible evidence available confirms only the existence of a common, but vague, socio-cultural designation of "nobility" associated with PIE society, such that Greek socio-cultural lexicon and Germanic proper names derived from this root remain insufficient to determine whether the concept was limited to the designation of an exclusive, socio-political elite, or whether it could possibly have been applied in the most inclusive sense to an inherent and ancestral "noble" quality which allegedly characterized all ethnic members of PIE society.

[17][18] By the early 1900s, the term "aryan" had come to be widely used in a racial sense, in which it referred to a hypothesized white, blond, and blue-eyed superior race.

[19] According to some archaeologists, PIE speakers cannot be assumed to have been a single, identifiable people or tribe, but were a group of loosely-related populations that were ancestral to the later, still partially prehistoric, Bronze Age Indo-Europeans.

However, this belief is not shared by most linguists, because proto-languages, like all languages before modern transport and communication, occupied small geographical areas over a limited time span, and were spoken by a set of close-knit communities– a tribe in the broad sense.

The hypothesis suggests that the Indo-Europeans, a patriarchal, patrilinear, and nomadic culture of the Pontic–Caspian steppe (which is now part northeastern Bulgaria and southeastern Romania, through Moldova, and southern and eastern Ukraine, through the northern Caucasus of southern Russia, and into the lower Volga region of western Kazakhstan), expanded into the area through several waves of migration during the 3rd millennium BCE, coinciding with the taming of the horse.

Leaving archaeological signs of their presence (see Corded Ware culture), they subjugated the supposedly peaceful, egalitarian, and matrilinear European neolithic farmers of Gimbutas' Old Europe.

Another argument, made by proponents of the steppe Urheimat (such as David Anthony) against Renfrew, points to the fact that ancient Anatolia is known to have been inhabited in the 2nd millennium BC by non-Indo-European-speaking peoples, namely the Hattians (perhaps North Caucasian-speaking), the Chalybes (language unknown), and the Hurrians (Hurro-Urartian).

The Kurgan hypothesis or steppe theory is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages spread out throughout Europe and parts of Asia.

It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE).

[30][citation needed] According to three autosomal DNA studies, haplogroups R1b and R1a, now the most common in Europe (R1a is also very common in South Asia) would have expanded from the Pontic steppes, along with the Indo-European languages; they also detected an autosomal component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic Europeans, which would have been introduced with paternal lineages R1b and R1a, as well as Indo-European languages.

[31][32][33] Studies which analysed ancient human remains in Ireland and Portugal suggest that R1b was introduced in these places along with autosomal DNA from the Pontic steppes.

Data so far collected indicate that there are two widely separated areas of high frequency, one in Eastern Europe, around Poland, Ukraine, and Russia, and the other in Southern Asia, around the Indo-Gangetic Plain, which is part of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal.

The historical and prehistoric possible reasons for this are the subject of on-going discussion and attention amongst population geneticists and genetic genealogists, and are considered to be of potential interest to linguists and archaeologists also.

[citation needed] A large, 2014 study by Underhill et al., using 16,244 individuals from over 126 populations from across Eurasia, concluded there was compelling evidence, that R1a-M420 originated in the vicinity of Iran.

[37] Ornella Semino et al. propose a postglacial (Holocene) spread of the R1a1 haplogroup from north of the Black Sea during the time of the Late Glacial Maximum, which was subsequently magnified by the expansion of the Kurgan culture into Europe and eastward.

[31][web 1] Remains of the "Eastern European hunter-gatherers" have been found in Mesolithic or early Neolithic sites in Karelia and Samara Oblast, Russia, and put under analysis.

The researchers found that these Caucasus hunters were probably the source of the farmer-like DNA in the Yamnaya, as the Caucasians were distantly related to the Middle Eastern people who introduced farming in Europe.

[web 1] Their genomes showed that a continued mixture of the Caucasians with Middle Eastern took place up to 25,000 years ago, when the coldest period in the last Ice Age started.

Our hypothesis is, therefore, that Indo-European languages derived from a secondary expansion from the Yamnaya culture region after the Neolithic farmers, possibly coming from Anatolia and settled there, developing pastoral nomadism.Spencer Wells suggests in a 2001 study that the origin, distribution and age of the R1a1 haplotype points to an ancient migration, possibly corresponding to the spread by the Kurgan people in their expansion across the Eurasian steppe around 3000 BC.

Anthony instead suggests a genetic and linguistic origin of proto-Indo-Europeans (the Yamnaya) in the Eastern European steppe north of the Caucasus, from a mixture of these two groups (EHG and CHG).

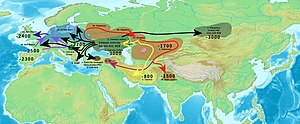

– Center: Steppe cultures

1 (black): Anatolian languages (archaic PIE)

2 (black): Afanasievo culture (early PIE)

3 (black) Yamnaya culture expansion (Pontic-Caspian steppe, Danube Valley ) (late PIE)

4A (black): Western Corded Ware

4B-C (blue & dark blue): Bell Beaker; adopted by Indo-European speakers

5A-B (red): Eastern Corded ware

5C (red): Sintashta (proto-Indo-Iranian)

6 (magenta): Andronovo

7A (purple): Indo-Aryans (Mittani)

7B (purple): Indo-Aryans (India)

[NN] (dark yellow): proto-Balto-Slavic

8 (grey): Greek

9 (yellow):Iranians

– [not drawn]: Armenian, expanding from western steppe