Geoffrey Chaucer

This is an accepted version of this page Geoffrey Chaucer (/ˈtʃɔːsər/ CHAW-sər; c. 1343 – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for The Canterbury Tales.

The first of the "Chaucer Life Records" appears in 1357, in the household accounts of Elizabeth de Burgh, the Countess of Ulster, when he became the noblewoman's page through his father's connections,[17] a common medieval form of apprenticeship for boys into knighthood or prestige appointments.

The countess was married to Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, the second surviving son of the king, Edward III, and the position brought the teenage Chaucer into the close court circle, where he was to remain for the rest of his life.

[18] In 1359, in the early stages of the Hundred Years' War, Edward III invaded France, and Chaucer travelled with Lionel of Antwerp, Elizabeth's husband, as part of the English army.

Thomas's great-grandson (Geoffrey's great-great-grandson), John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, was the heir to the throne designated by Richard III before he was deposed.

Geoffrey's other children probably included Elizabeth Chaucy, a nun at Barking Abbey,[21][22] Agnes, an attendant at Henry IV's coronation; and another son, Lewis Chaucer.

He became a member of the royal court of Edward III as a valet de chambre, yeoman, or esquire on 20 June 1367, a position which could entail a wide variety of tasks.

Around this time, Chaucer is believed to have written The Book of the Duchess in honour of Blanche of Lancaster, the late wife of John of Gaunt, who died in 1369 of the plague.

Later documents suggest it was a mission, along with Jean Froissart, to arrange a marriage between the future King Richard II and a French princess, thereby ending the Hundred Years' War.

In 1378, Richard II sent Chaucer as an envoy (secret dispatch) to the Visconti and Sir John Hawkwood, English condottiere (mercenary leader) in Milan.

[29] A possible indication that his career as a writer was appreciated came when Edward III granted Chaucer "a gallon of wine daily for the rest of his life" for some unspecified task.

[40] No major works were begun during his tenure, but he did conduct repairs on Westminster Palace, St. George's Chapel, Windsor, continued building the wharf at the Tower of London and built the stands for a tournament held in 1390.

The poem refers to John and Blanche in allegory as the narrator relates the tale of "A long castel with walles white/Be Seynt Johan, on a ryche hil" (1318–1319) who is mourning grievously after the death of his love, "And goode faire White she het/That was my lady name ryght" (948–949).

Fortune, in turn, does not understand Chaucer's harsh words to her for she believes that she has been kind to him, claims that he does not know what she has in store for him in the future, but most importantly, "And eek thou hast thy beste frend alyve" (32, 40, 48).

Fortune turns her attention to three princes whom she implores to relieve Chaucer of his pain and "Preyeth his beste frend of his noblesse/That to som beter estat he may atteyne" (78–79).

Chaucer respected and admired Christians and was one himself, as he wrote in Canterbury Tales, "now I beg all those that listen to this little treatise, or read it, that if there be anything in it that pleases them, they thank our Lord Jesus Christ for it, from whom proceeds all understanding and goodness.

[59] The equatorie of the planetis is a scientific work similar to the Treatise and sometimes ascribed to Chaucer because of its language and handwriting, an identification which scholars no longer deem tenable.

Acceptable, alkali, altercation, amble, angrily, annex, annoyance, approaching, arbitration, armless, army, arrogant, arsenic, arc, artillery and aspect are just some of almost two thousand English words first attested in Chaucer.

Writers of the 17th and 18th centuries, such as John Dryden, admired Chaucer for his stories but not for his rhythm and rhyme, as few critics could then read Middle English and the text had been butchered by printers, leaving a somewhat unadmirable mess.

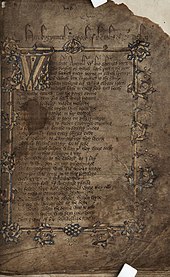

"[84] The large number of surviving manuscripts of Chaucer's works is testimony to the enduring interest in his poetry prior to the arrival of the printing press.

Some scholars contend that 16th-century editions of Chaucer's Works set the precedent for all other English authors regarding presentation, prestige and success in print.

Probably the most significant aspect of the growing apocrypha is that beginning with Thynne's editions, it began to include medieval texts that made Chaucer appear as a proto-Protestant Lollard, primarily the Testament of Love and The Plowman's Tale.

Since the Testament of Love mentions its author's part in a failed plot (book 1, chapter 6), his imprisonment, and (perhaps) a recantation of (possibly Lollardism) heresy, all this was associated with Chaucer.

[89] The compilation and printing of Chaucer's works was, from its beginning, a political enterprise, since it was intended to establish an English national identity and history that grounded and authorised the Tudor monarchy and church.

In his 1598 edition of the Works, Speght (probably taking cues from Foxe) made good use of Usk's account of his political intrigue and imprisonment in the Testament of Love to assemble a largely fictional "Life of Our Learned English Poet, Geffrey Chaucer".

Speght's "Life" presents readers with an erstwhile radical in troubled times much like their own, a proto-Protestant who eventually came round to the king's views on religion.

Ironically – and perhaps consciously so – an introductory, apologetic letter in Speght's edition from Francis Beaumont defends the unseemly, "low", and bawdy bits in Chaucer from an elite, classicist position.

Speght's "Life of Chaucer" echoes Foxe's own account, which is itself dependent upon the earlier editions that added the Testament of Love and The Plowman's Tale to their pages.

The text of Urry's edition has often been criticised by subsequent editors for its frequent conjectural emendations, mainly to make it conform to his sense of Chaucer's metre.

In 1994, literary critic Harold Bloom placed Chaucer among the greatest Western writers of all time, and in 1997 expounded on William Shakespeare's debt to the author.