Geometric design of roads

The geometric design of roads is the branch of highway engineering concerned with the positioning of the physical elements of the roadway according to standards and constraints.

The basic objectives in geometric design are to optimize efficiency and safety while minimizing cost and environmental damage.

Geometric design also affects an emerging fifth objective called "livability", which is defined as designing roads to foster broader community goals, including providing access to employment, schools, businesses and residences, accommodate a range of travel modes such as walking, bicycling, transit, and automobiles, and minimizing fuel use, emissions and environmental damage.

Design guidelines take into account speed, vehicle type, road grade (slope), view obstructions, and stopping distance.

An open source version of the green book is published online by The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) office in Zimbabwe.

[2] When a driver is driving on a sag curve at night, the sight distance is limited by the higher grade in front of the vehicle.

If a horizontal curve has a high speed and a small radius, an increased superelevation (bank) is needed in order to assure safety.

If there is an object obstructing the view around a corner or curve, the engineer must work to ensure that drivers can see far enough to stop to avoid an accident or accelerate to join traffic.

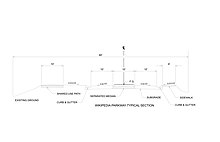

The cross-sectional shape of a road surface, in particular in connection to its role in managing runoff, is called "crown".

[8] Throughput is maximal at 18 miles per hour (29 km/h); as lane width decreases to 3.0 to 3.1 metres (9.8 to 10.2 ft), traffic speed diminishes, and so does the interval between vehicles.

In tangent (straight) sections, the road surface cross slope is commonly 1—2% to enable water to drain from the roadway.

This causes a greater proportion of centripetal force to supplant the tyre friction that would otherwise be needed to negotiate the curve.

Superelevation slopes of 4 to 10% are applied in order to aid motorists in safely traversing these sections, while maintaining vehicle speed throughout the length of the curve.

An upper bound of 12% was chosen to meet the demands of construction and maintenance practices, as well as to limit the difficulty of driving a steeply cross-sloped curve at low speeds.

[5] The equation for the desired radius of a curve, shown below, takes into account the factors of speed and superelevation (e).

This equation can be algebraically rearranged to obtain desired rate of superelevation, using input of the roadway's designated speed and curve radius.

The American Association of State Highway and Transportation officials (AASHTO) provides a table from which desired superelevation rates can be interpolated, based on the designated speed and radius of a curved section of roadway.

Recent research has shown that, considering rollover risk for heavy vehicles (semitrailers & buses), which have a relatively high centre-of-gravity, the above equation yields cross slope values which are too low.

Collisions tend to be more frequent in locations where a sudden change in road character violates the driver's expectations.

The concept of design consistency addresses this by comparing adjacent road segments and identifying sites with changes the driver might find sudden or unexpected.

Locations with large changes in the predicted operating speed are likely to benefit from additional design effort.

Sight distance, in the context of road design, is defined as "the length of roadway ahead visible to the driver".

Typically the design sight distance allows a below-average driver to stop in time to avoid a collision.

The decision sight distance is "distance required for a driver to detect an unexpected or otherwise difficult-to-perceive information source or hazard in a roadway environment that may be visually cluttered, recognize the hazard or its threat potential, select an appropriate speed and path, and initiate and complete the required maneuver safely and efficiently".

Uncontrolled and yield (give way) controlled intersections require large sight triangles clear of obstructions in order to operate safely.

Although not needed during normal operations, additional sight distance should be provided for signal malfunctions and power outages.

[citation needed] Many roads were created long before the current sight distance standards were adopted, and the financial burden on many jurisdictions would be formidable to: acquire and maintain additional right-of-way; redesign roadbeds on all of them; or implement future projects on rough terrain, or environmentally sensitive areas.

Hill Blocks View signs can be used where crest vertical curves restrict sight distance.

[Note 2] The care and focus ordinarily required of a driver against certain types of hazards may be somewhat amplified on roads with lower functional classification.

[34] For this reason, full corner sight distance is almost never required for individual driveways in urban high-density residential areas, and street parking is commonly permitted within the right-of-way.