Centripetal force

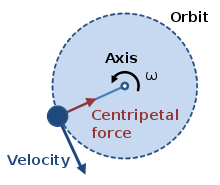

The direction of the centripetal force is always orthogonal to the motion of the body and towards the fixed point of the instantaneous center of curvature of the path.

Isaac Newton described it as "a force by which bodies are drawn or impelled, or in any way tend, towards a point as to a centre".

[2] In Newtonian mechanics, gravity provides the centripetal force causing astronomical orbits.

One common example involving centripetal force is the case in which a body moves with uniform speed along a circular path.

The centripetal force is directed at right angles to the motion and also along the radius towards the centre of the circular path.

In particle accelerators, velocity can be very high (close to the speed of light in vacuum) so the same rest mass now exerts greater inertia (relativistic mass) thereby requiring greater force for the same centripetal acceleration, so the equation becomes:[11]

Below are three examples of increasing complexity, with derivations of the formulas governing velocity and acceleration.

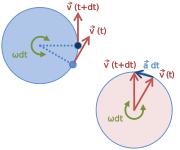

Uniform circular motion refers to the case of constant rate of rotation.

negative shows that the acceleration is pointed towards the center of the circle (opposite the radius), hence it is called "centripetal" (i.e. "center-seeking").

The rotation itself is represented by the angular velocity vector Ω, which is normal to the plane of the orbit (using the right-hand rule) and has magnitude given by: with θ the angular position at time t. In this subsection, dθ/dt is assumed constant, independent of time.

In words, the acceleration is pointing directly opposite to the radial displacement r at all times, and has a magnitude:

where vertical bars |...| denote the vector magnitude, which in the case of r(t) is simply the radius r of the path.

The upper panel in the image at right shows a ball in circular motion on a banked curve.

The curve is banked at an angle θ from the horizontal, and the surface of the road is considered to be slippery.

Apart from any acceleration that might occur in the direction of the path, the lower panel of the image above indicates the forces on the ball.

Consequently, the ball is in a stable path when the angle of the road is set to satisfy the condition:

In words, this equation states that for greater speeds (bigger |v|) the road must be banked more steeply (a larger value for θ), and for sharper turns (smaller r) the road also must be banked more steeply, which accords with intuition.

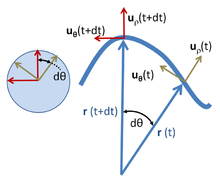

[17] As a generalization of the uniform circular motion case, suppose the angular rate of rotation is not constant.

This case is used to demonstrate a derivation strategy based on a polar coordinate system.

The other unit vector for polar coordinates, uθ is perpendicular to ur and points in the direction of increasing θ.

The above results can be derived perhaps more simply in polar coordinates, and at the same time extended to general motion within a plane, as shown next.

Unit vector uθ also travels with the particle and stays orthogonal to uρ.

Substituting the derivative of uρ into the expression for velocity: To obtain the acceleration, another time differentiation is done: Substituting the derivatives of uρ and uθ, the acceleration of the particle is:[21] As a particular example, if the particle moves in a circle of constant radius R, then dρ/dt = 0, v = vθ, and:

[22] For trajectories other than circular motion, for example, the more general trajectory envisioned in the image above, the instantaneous center of rotation and radius of curvature of the trajectory are related only indirectly to the coordinate system defined by uρ and uθ and to the length |r(t)| = ρ. Consequently, in the general case, it is not straightforward to disentangle the centripetal and Euler terms from the above general acceleration equation.

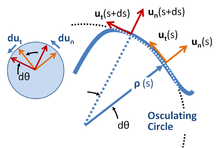

[26] Unit vectors are formed as shown in the image at right, both tangential and normal to the path.

[29] Distance along the path of the particle is the arc length s, considered to be a known function of time.

The required distance ρ(s) at arc length s is defined in terms of the rate of rotation of the tangent to the curve, which in turn is determined by the path itself.

The radius of curvature is introduced completely formally (without need for geometric interpretation) as:

From a qualitative standpoint, the path can be approximated by an arc of a circle for a limited time, and for the limited time a particular radius of curvature applies, the centrifugal and Euler forces can be analyzed on the basis of circular motion with that radius.

To illustrate the above formulas, let x, y be given as: Then: which can be recognized as a circular path around the origin with radius α.