Geometric algebra

The geometric product was first briefly mentioned by Hermann Grassmann,[1] who was chiefly interested in developing the closely related exterior algebra.

For several decades, geometric algebras went somewhat ignored, greatly eclipsed by the vector calculus then newly developed to describe electromagnetism.

The term "geometric algebra" was repopularized in the 1960s by David Hestenes, who advocated its importance to relativistic physics.

Geometric algebra has been advocated, most notably by David Hestenes[4] and Chris Doran,[5] as the preferred mathematical framework for physics.

Proponents claim that it provides compact and intuitive descriptions in many areas including classical and quantum mechanics, electromagnetic theory, and relativity.

Hestenes's original approach was axiomatic,[8] "full of geometric significance" and equivalent to the universal[a] Clifford algebra.

The exterior product is naturally extended as an associative bilinear binary operator between any two elements of the algebra, satisfying the identities where the sum is over all permutations of the indices, with

[18] The role the Pfaffian plays can be understood from a geometric viewpoint by developing Clifford algebra from simplices.

(The total number of basis vectors that square to zero is also invariant, and may be nonzero if the degenerate case is allowed.)

as the empty product, forms a basis for the entire geometric algebra (an analogue of the PBW theorem).

[22] Some authors use the term "versor product" to refer to the frequently occurring case where an operand is "sandwiched" between operators.

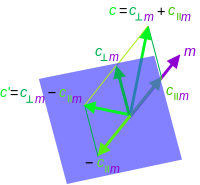

Blades are important since geometric operations such as projections, rotations and reflections depend on the factorability via the exterior product that (the restricted class of)

The paper (Dorst 2002) gives a full treatment of several different inner products developed for geometric algebras and their interrelationships, and the notation is taken from there.

However, such a general linear transformation allows arbitrary exchanges among grades, such as a "rotation" of a scalar into a vector, which has no evident geometric interpretation.

With the natural restriction to preserving the induced exterior algebra, the outermorphism of the linear transformation is the unique[k] extension of the versor.

: Dotting the "Pauli vector" (a dyad): In physics, the main applications are the geometric algebra of Minkowski 3+1 spacetime,

Homogeneous models generally refer to a projective representation in which the elements of the one-dimensional subspaces of a vector space represent points of a geometry.

With a suitable identification of subspaces to represent points, lines and planes, the versors of this algebra represent all proper Euclidean isometries, which are always screw motions in 3-dimensional space, along with all improper Euclidean isometries, which includes reflections, rotoreflections, transflections, and point reflections.

The conformal model discussed below is homogeneous, as is "Conic Geometric Algebra",[36] and see Plane-based geometric algebra for discussion of homogeneous models of elliptic and hyperbolic geometry compared with the Euclidean geometry derived from PGA.

This allows all conformal transformations to be performed as rotations and reflections and is covariant, extending incidence relations of projective geometry to rounds objects such as circles and spheres.

A fast changing and fluid area of GA, CGA is also being investigated for applications to relativistic physics.

is called a rotor if it is a proper rotation (as it is if it can be expressed as a product of an even number of vectors) and is an instance of what is known in GA as a versor.

By designating the unit bivector of this plane as the imaginary number this path vector can be conveniently written in complex exponential form and the derivative with respect to angle is For example, torque is generally defined as the magnitude of the perpendicular force component times distance, or work per unit angle.

Also developed are the concept of vector manifold and geometric integration theory (which generalizes differential forms).

Subsequently, Rudolf Lipschitz in 1886 generalized Clifford's interpretation of the quaternions and applied them to the geometry of rotations in

Vector analysis was motivated by James Clerk Maxwell's studies of electromagnetism, and specifically the need to express and manipulate conveniently certain differential equations.

Physicists and mathematicians alike readily adopted it as their geometrical toolkit of choice, particularly following the influential 1901 textbook Vector Analysis by Edwin Bidwell Wilson, following lectures of Gibbs.

Progress on the study of Clifford algebras quietly advanced through the twentieth century, although largely due to the work of abstract algebraists such as Élie Cartan, Hermann Weyl and Claude Chevalley.

[5] David Hestenes reinterpreted the Pauli and Dirac matrices as vectors in ordinary space and spacetime, respectively, and has been a primary contemporary advocate for the use of geometric algebra.

In computer graphics and robotics, geometric algebras have been revived in order to efficiently represent rotations and other transformations.