Geophysical survey (archaeology)

Features are the non-portable part of the archaeological record, whether standing structures or traces of human activities left in the soil.

Geophysical instruments can detect buried features when their physical properties contrast measurably with their surroundings.

Survey results can be used to guide excavation and to give archaeologists insight into the patterning of non-excavated parts of the site.

Appropriate instrumentation, survey design, and data processing are essential for success, and must be adapted to the unique geology and archaeological record of each site.

Another challenge is to detect subtle and often very small features – which may be as ephemeral as organic staining from decayed wooden posts - and distinguish them from rocks, roots, and other natural "clutter".

To accomplish this requires not only sensitivity, but also high density of data points, usually at least one and sometimes dozens of readings per square meter.

These methods can resolve many types of archaeological features, are capable of high sample density surveys of very large areas, and of operating under a wide range of conditions.

[2][3] Although EM conductivity instruments are generally less sensitive than resistance meters to the same phenomena, they do have a number of unique properties.

Some EM conductivity instruments are also capable of measuring magnetic susceptibility, a property that is becoming increasingly important in archaeological studies.

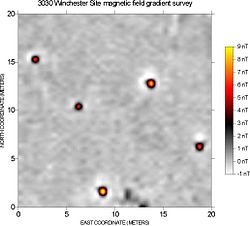

Different materials below the ground can cause local disturbances in the Earth's magnetic field that are detectable with sensitive magnetometers.

Magnetometers react very strongly to iron and steel, brick, burned soil, and many types of rock, and archaeological features composed of these materials are very detectable.

The chief limitation of magnetometer survey is that subtle features of interest may be obscured by highly magnetic geologic or modern materials.

Sometimes external data loggers are attached to such detectors which collect information about detected materials and corresponding gps coordinates for further processing.

Lidar can also provide archaeologists with the ability to create high-resolution digital elevation models (DEMs) of archaeological sites that can reveal micro-topography that are otherwise hidden by vegetation.

Survey usually involves walking with the instrument along closely spaced parallel traverses, taking readings at regular intervals.

With the corners of the grids as known reference points, the instrument operator uses tapes or marked ropes as a guide when collecting data.

Statistical filters may be designed to enhance features of interest (based on size, strength, orientation, or other criteria), or suppress obscuring modern or natural phenomena.

When geophysical data are rendered graphically, the interpreter can more intuitively recognize cultural and natural patterns and visualize the physical phenomena causing the detected anomalies.

Rapid data collection has also made achieving the high sample densities necessary to resolve small or subtle features practical.

Advances in processing and imaging software have made it possible to detect, display, and interpret subtle archaeological patterning within the geophysical data.