George Henry Thomas

Thomas won one of the first Union victories in the war, at Mill Springs in Kentucky, and served in important subordinate commands at Perryville and Stones River.

In the Franklin–Nashville Campaign of 1864, he achieved one of the most decisive victories of the war, destroying the army of Confederate General John Bell Hood, his former student at West Point, at the Battle of Nashville.

Thomas had a successful record in the Civil War, but he failed to achieve the historical acclaim of some of his contemporaries, such as Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman.

[4] George Thomas, his sisters, and his widowed mother were forced to flee from their home and hide in the nearby woods during Nat Turner's 1831 slave rebellion.

This was a major event in the formation of his views on slavery; that the idea of the contented slave in the care of a benevolent overlord was a sentimental myth.

[6] Christopher Einolf, in contrast wrote "For George Thomas, the view that slavery was needed as a way of controlling blacks was supported by his personal experience of Nat Turner's Rebellion.

"[7] A traditional story is that Thomas taught as many as 15 of his family's slaves to read, violating a Virginia law that prohibited this,[8] and despite the wishes of his father.

Entering at age 20, Thomas was known to his fellow cadets as "Old Tom," and he became instant friends with his roommates, William T. Sherman and Stewart Van Vliet.

[11] Thomas's first assignment with his artillery regiment began in late 1840 at the primitive outpost of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in the Seminole Wars, where his troops performed infantry duty.

[13] In Mexico, Thomas led a gun crew with distinction at the battles of Fort Brown, Resaca de la Palma, Monterrey, and Buena Vista, receiving two more brevet promotions.

In 1851, he returned to West Point as a cavalry and artillery instructor, where he established a close professional and personal relationship with another Virginia officer, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee, the Academy superintendent.

[17] In the spring of 1854, Thomas's artillery regiment was transferred to California and he led two companies to San Francisco via the Isthmus of Panama, and then on a grueling overland march to Fort Yuma.

There was a suspicion as the Civil War drew closer that Davis had been assembling and training a combat unit of elite U.S. Army officers who harbored Southern sympathies, and Thomas's appointment to this regiment implied that his colleagues assumed he would support his native state of Virginia in a future conflict.

[18] Thomas resumed his close ties with the second-in-command of the regiment, Robert E. Lee, and the two officers traveled extensively together on detached service for court-martial duty.

On August 26, 1860, during a clash with a Comanche warrior, Thomas was wounded by an arrow passing through the flesh near his chin area and sticking into his chest at Clear Fork, Brazos River, Texas.

[21] At the outbreak of the Civil War, 19 of the 36 officers in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry resigned, including three of Thomas's superiors—Albert Sidney Johnston, Robert E. Lee, and William J.

During the economic hard times in the South after the war, Thomas sent some money to his sisters, who angrily refused to accept it, declaring they had no brother.

[28] In the First Bull Run Campaign, he commanded a brigade under Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson in the Shenandoah Valley,[29] but all of his subsequent assignments were in the Western Theater.

Reporting to Maj. Gen. Robert Anderson in Kentucky, Thomas was assigned to training recruits and to command an independent force in the eastern half of the state.

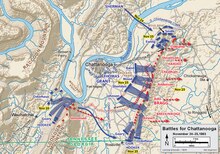

He was in charge of the most important part of the maneuvering from Decherd to Chattanooga during the Tullahoma Campaign (June 22 – July 3, 1863) and the crossing of the Tennessee River.

At the Battle of Chickamauga on September 19, 1863, now commanding the XIV Corps, he once again held a desperate position against Bragg's onslaught while the Union line on his right collapsed.

Thomas rallied broken and scattered units together on Horseshoe Ridge to prevent a significant Union defeat from becoming a hopeless rout.

Thomas was appointed a major general in the regular army, with date of rank of his Nashville victory, and received the Thanks of Congress:[35] ... to Major-General George H. Thomas and the officers and soldiers under his command for their skill and dauntless courage, by which the rebel army under General Hood was signally defeated and driven from the state of Tennessee.Thomas may have resented his delayed promotion to major general (which made him junior by date of rank to Sheridan); upon receiving the telegram announcing it, he remarked to Surgeon George Cooper: "I suppose it is better late than never, but it is too late to be appreciated.

[37] After the end of the Civil War, Thomas commanded the Department of the Cumberland in Kentucky and Tennessee, and at times also West Virginia and parts of Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama, through 1869.

This is, of course, intended as a species of political cant, whereby the crime of treason might be covered with a counterfeit varnish of patriotism, so that the precipitators of the rebellion might go down in history hand in hand with the defenders of the government, thus wiping out with their own hands their own stains; a species of self-forgiveness amazing in its effrontery, when it is considered that life and property—justly forfeited by the laws of the country, of war, and of nations, through the magnanimity of the government and people—was not exacted from them.President Andrew Johnson offered Thomas the rank of lieutenant general—with the intent to eventually replace Grant, a Republican and future president, with Thomas as general in chief—but the ever-loyal Thomas asked the Senate to withdraw his name for that nomination because he did not want to be party to politics.

He died there of a stroke on March 28, 1870, while writing an answer to an article criticizing his military career by his wartime rival John Schofield.

[citation needed] Thomas has generally been held in high esteem by Civil War historians; Bruce Catton and Carl Sandburg wrote glowingly of him, and many[who?]

In his Personal Memoirs, Grant minimized Thomas's contributions, particularly during the Franklin-Nashville Campaign, saying his movements were "always so deliberate and so slow, though effective in defence.

After noting that Thomas, unlike his fellow Virginian Lee, stood by the Union, Sherman wrote:During the whole war his services were transcendent, winning the first substantial victory at Mill Springs in Kentucky, January 20th, 1862, participating in all the campaigns of the West in 1862-3-4, and finally, December 16th, 1864 annihilating the army of Hood, which in mid winter had advanced to Nashville to besiege him.

Thomas's torn loyalties during the Civil War are briefly discussed in Chapter XIX of MacKinlay Kantor's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel "Andersonville" (1955).