George I of Great Britain

As the senior Protestant descendant of his great-grandfather James VI and I, George inherited the British throne following the deaths in 1714 of his mother, Sophia, and his second cousin Anne, Queen of Great Britain.

During George's reign the powers of the monarchy diminished, and Britain began a transition to the modern system of cabinet government led by a prime minister.

Towards the end of his reign, actual political power was held by Robert Walpole, now recognised as Britain's first de facto prime minister.

[4] The parents were absent for almost a year (1664–1665) during a long convalescent holiday in Italy but Sophia corresponded regularly with her sons' governess and took a great interest in their upbringing, even more so upon her return.

The following year, Frederick Augustus was informed of the adoption of primogeniture, meaning he would no longer receive part of his father's territory as he had expected.

Threatened with the scandal of an elopement, the Hanoverian court, including George's brothers and mother, urged the lovers to desist, but to no avail.

According to diplomatic sources from Hanover's enemies, in July 1694, the Swedish count was killed, possibly with George's connivance, and his body thrown into the river Leine weighted with stones.

The murder was claimed to have been committed by four of Ernest Augustus's courtiers, one of whom, Don Nicolò Montalbano, was paid the enormous sum of 150,000 thalers, about one hundred times the annual salary of the highest-paid minister.

With her father's agreement, George had Sophia Dorothea imprisoned in Ahlden House in her native Celle, where she stayed until she died more than thirty years later.

[15] His court in Hanover was graced by many cultural icons such as the mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz and the composers George Frideric Händel and Agostino Steffani.

Shortly after George's accession to his paternal duchy, Prince William, Duke of Gloucester, who was second-in-line to the English and Scottish thrones, died.

[17] In August 1701, George was invested with the Order of the Garter and, within six weeks, the nearest Catholic claimant to the thrones, the former king James II, died.

The Holy Roman Empire, the United Dutch Provinces, England, Hanover and many other German states opposed Philip's right to succeed because they feared that the French House of Bourbon would become too powerful if it also controlled Spain.

In response the English Parliament passed the Alien Act 1705, which threatened to restrict Anglo-Scottish trade and cripple the Scottish economy if the Estates did not agree to the Hanoverian succession.

[25] Eventually, in 1707, both Parliaments agreed on a Treaty of Union, which united England and Scotland into a single political entity, the Kingdom of Great Britain, and established the rules of succession as laid down by the Act of Settlement 1701.

After the rebellion was defeated, although there were some executions and forfeitures, George acted to moderate the Government's response, showed leniency, and spent the income from the forfeited estates on schools for Scotland and paying off part of the national debt.

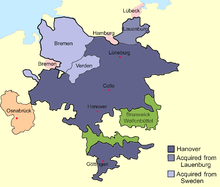

Prince George Augustus encouraged opposition to his father's policies, including measures designed to increase religious freedom in Britain and expand Hanover's German territories at Sweden's expense.

The King, supposedly following custom, appointed the Lord Chamberlain (Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle) as one of the baptismal sponsors of the child.

The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht had recognised the grandson of Louis XIV of France, Philip V, as king of Spain on the condition that he gave up his rights to succeed to the French throne.

In 1717 Townshend was dismissed, and Walpole resigned from the Cabinet over disagreements with their colleagues;[43] Stanhope became supreme in foreign affairs, and Sunderland the same in domestic matters.

[55] The Company enticed bondholders to convert their high-interest, irredeemable bonds to low-interest, easily tradeable stocks by offering apparently preferential financial gains.

[68] Claims that George had received free stock as a bribe[69] are not supported by evidence; indeed receipts in the Royal Archives show that he paid for his subscriptions and that he lost money in the crash.

Unlike his predecessor, Queen Anne, George rarely attended meetings of the cabinet; most of his communications were in private, and he only exercised substantial influence with respect to British foreign policy.

[76] George was ridiculed by his British subjects;[77] some of his contemporaries, such as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, thought him unintelligent on the grounds that he was wooden in public.

[82] However, in mainland Europe, he was seen as a progressive ruler supportive of the Enlightenment who permitted his critics to publish without risk of severe censorship, and provided sanctuary to Voltaire when the philosopher was exiled from Paris in 1726.

[77] European and British sources agree that George was reserved, temperate and financially prudent;[34] he disliked being in the public light at social events, avoided the royal box at the opera and often travelled incognito to the homes of friends to play cards.

They in turn, influenced British authors of the first half of the twentieth century such as G. K. Chesterton, who introduced further anti-German and anti-Protestant bias into the interpretation of George's reign.

However, in the wake of World War II continental European archives were opened to historians of the later twentieth century and nationalistic anti-German feeling subsided.

Perhaps his own mother summed him up when "explaining to those who regarded him as cold and overserious that he could be jolly, that he took things to heart, that he felt deeply and sincerely and was more sensitive than he cared to show.

"[6] Whatever his true character, he ascended a precarious throne, and either by political wisdom and guile, or through accident and indifference, he left it secure in the hands of the Hanoverians and of Parliament.