George Washington and slavery

They built their own community around marriage and family, though Washington allocated the enslaved to his farms according to business needs, causing many husbands to live separately from their wives and children during the work week.

Towards the end of the 17th century, English policy shifted in favor of retaining cheap labor rather than shipping it to the colonies, and the supply of indentured servants in Virginia began to dry up; by 1715, annual immigration was in the hundreds, compared with 1,500–2,000 in the 1680s.

[57] There are few sources which shed light on living conditions in these cabins, but one visitor in 1798 wrote, "husband and wife sleep on a mean pallet, the children on the ground; a very bad fireplace, some utensils for cooking, but in the middle of this poverty some cups and a teapot".

[90] The living arrangements left some enslaved females alone and vulnerable, and the Mount Vernon research historian Mary V. Thompson writes that relationships "could have been the result of mutual attraction and affection, very real demonstrations of power and control, or even exercises in the manipulation of an authority figure".

Over the years Washington became increasingly skeptical about absenteeism due to sickness among his enslaved population and concerned about the diligence or ability of his overseers in recognizing genuine cases of physical illness.

[99] Tools were regularly lost or damaged, thus stopping work, and Washington despaired of employing innovations that might improve efficiency because he assumed enslaved workers were too clumsy to operate the new machinery involved.

"[131] He began to express the growing rift with Great Britain in terms of slavery, stating in the summer of 1774 that the British authorities were "endeavouring by every piece of Art & despotism to fix the Shackles of Slavry [sic]" upon the colonies.

"[132] The hypocrisy or paradox inherent in slave owners characterizing a war of independence as a struggle for their own freedom from slavery was not lost on the British writer Samuel Johnson, who asked, "How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?

"[133][134] As if answering Johnson, Washington wrote to a friend in August 1774, "The crisis is arrived when we must assert our rights, or submit to every imposition that can be heaped upon us, till custom and use shall make us tame and abject slaves, as the blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway.

He reversed his position on free African Americans when the royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation in November 1775 offering freedom to rebel-owned slaves who enlisted in the British forces.

[147] In the exchange of letters, a conflicted Washington expressed a desire "to get quit of Negroes", but made clear his reluctance to sell them at a public venue and his wish that "husband and wife, and Parents and children are not separated from each other".

[166][167] It is likely that revolutionary rhetoric about the rights of men, the close contact with young antislavery officers who served with Washington – such as Laurens, the Marquis de Lafayette and Alexander Hamilton – and the influence of northern colleagues were contributory factors in that process.

As Lafayette forged ahead with his plan, Washington offered encouragement but expressed concern in 1786 about "much inconvenience and mischief" an abrupt emancipation might generate, and he gave no tangible support to the idea.

"[185] James Thomas Flexner's interpretation is somewhat different from Lacy Ford's: "Washington was willing to back publicly the Methodists' petition for gradual emancipation if the proposal showed the slightest possibility of being given consideration by the Virginia legislature.

"[185] Flexner adds that, if Washington had been more audacious in pursuing emancipation in Virginia, then "he undoubtedly would have failed to achieve the end of slavery, and he would certainly have made impossible the role he played in the Constitutional Convention and the Presidency.

[197][38] Washington significantly reduced his slave purchases after the war, though it is not clear whether this was a moral or practical decision; he repeatedly stated that his inventory and its potential progeny were adequate for his current and foreseeable needs.

"[208] Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention in 1787, during which it became obvious how explosive the slavery issue was, and how willing the antislavery faction was to accept the preservation of this oppressive institution to ensure national unity and the establishment of a strong federal government.

To make the Adults among them as easy & as comfortable in their circumstances as their actual state of ignorance & improvidence would admit; & to lay a foundation to prepare the rising generation for a destiny different from that in which they were born; afforded some satisfaction to my mind, & could not I hoped be displeasing to the justice of the Creator.

[217] Other historians dispute Wiencek's conclusion; Henriques and Joseph Ellis concur with Philip Morgan's opinion that Washington experienced no epiphanies in a "long and hard-headed struggle" in which there was no single turning point.

Morgan argues that Humphreys' passage is the "private expression of remorse" from a man unable to extricate himself from the "tangled web" of "mutual dependency" on slavery, and that Washington believed public comment on such a divisive subject was best avoided for the sake of national unity.

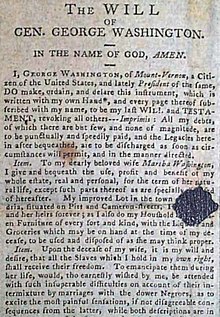

[238] His abolitionist aspirations for the nation centered around the hope that slavery would disappear naturally over time with the prohibition of slave imports in 1808, the earliest date such legislation could be passed as agreed at the Constitutional Convention.

Indeed, the gradual dying out of slavery remained possible, until Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin in 1793 which led within five years to a vastly greater demand for slave labor.

[245][246] It is demonstrably clear that on this Estate I have more working Negroes by a full moiety, than can be employed to any advantage in the farming system; and I shall never turn to Planter thereon...To sell the surplus I cannot, because I am principled against this kind of traffic in the human species...

Washington concluded his instructions to Lear with a private passage in which he expressed repugnance at owning slaves and declared that the principal reason for selling the land was to raise the finances that would allow him to liberate them.

[261][262] Wiencek speculates that, because Washington gave such serious consideration to freeing his slaves knowing full well the political ramifications that would follow, one of his goals was to make a public statement that would sway opinion towards abolition.

[301] Custis later wrote that "although many of them, with a view to their liberation, had been instructed in mechanic trades, yet they succeeded very badly as freemen; so true is the axiom, 'that the hour which makes man a slave, takes half his worth away'".

The son-in-law of Custis's sister wrote in 1853 that the descendants of those who remained slaves, many of them now in his possession, had been "prosperous, contented and happy", while those who had been freed had led a life of "vice, dissipation and idleness" and had, in their "sickness, age and poverty", become a burden to his in-laws.

[311] In this narrative, slaves idolized Washington and wept at his deathbed, and in an 1807 biography, Aaron Bancroft wrote, "In domestick [sic] and private life, he blended the authority of the master with the care and kindness of the guardian and friend.

Historians have found evidence of several reasons for that failure, including Washington's fears of disunion, the racism of many other Virginians, the problem of compensating owners, slaves' lack of education, and the unwillingness of Virginia's leaders to seriously consider such a step.

[272][273] In 1929, a plaque was embedded in the ground at Mount Vernon less than 50 yards (45 m) from the crypt housing the remains of Washington and Martha, marking a plot neglected by both groundsmen and tourist guides where slaves had been buried in unmarked graves.