Gerard Krefft

[7][8] Also, along with several significant others — such as Charles Darwin, during his 1836 visit to the Blue Mountains,[9] Edward Wilson, the proprietor of the Melbourne Argus,[10] and George Bennett, one of the trustees of the Australian Museum[11] — Krefft expressed considerable concern in relation to the effects of the expanding European settlement upon the indigenous population.

[15] According to Nancarrow (2007, p. 5), Annie McPhail was the Australian-born daughter of Scottish bounty immigrants, who had arrived in Australia in 1837 to work for George Bowman, and she was five months pregnant at the time of her marriage to Krefft.

Consequently, and in order to avoid the prochronistic mistake of viewing the past through the eyes of the present, and given, it is important to note that the widely used "umbrella" terms of natural history and natural historian (or naturalist) were generally understood (and variously applied) in the mid-1800s to identify the collective endeavours of an extremely wide range of diverse enterprises that are, now, separately identified as, at least, the disciplines of anthropology, astronomy, biology, botany, ecology, entomology, ethnology, geology, herpetology, ichthyology, mammalogy, mineralogy, mycology, ornithology, palaeontology, and zoology.

[48] Krefft's professional career, his museum curatorship, his interactions with the Anglo-Australian trustees of the Australian Museum,[52] and his professional endeavours to disseminate the latest scientific understandings to the people of New South Wales in the mid-1800s coincided with an entirely new awareness of the world, derived from the abundance of ongoing scientific advances, technological innovations, geological discoveries, and colonial explorations, and the emerging rational skepticism, expressed by Bishop John Colenso (Colenso, 1862, 1865, 1971, 1873, 1879) and others, about the objective veracity of specific Christian scriptures (e.g., Noah's Ark, the Deluge, the Crossing of the Red Sea, the Exodus, etc.

The lecture, chaired by the devout Irish Catholic layman Justice Peter Faucett,[56] Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales — who would later (in 1875) express the judicial opinion that Krefft's dismissal from his Museum curatorship was justified — was well attended.

In a paper read to the Linnean Society of London on 1 July 1858 — written separately from, but presented jointly with, that of Alfred Russel Wallace (i.e., Darwin & Wallace, 1858) — that was firmly based upon the foundations of the extensive and varied evidence provided by his comprehensive in-the-field observations over two decades,[62] Darwin was the first to propose "natural selection" (as opposed to the "artificial selection" of livestock- or plant-breeders)[63] — thereby "[substituting] a natural for a supernatural explanation of the material organic universe" (Abbott, 1912, p. 18) — as the process responsible for the diversity of life on Earth.

[64][65] Along with the Sydney botanist, Robert D. FitzGerald, and the Melbourne economist, Professor William Edward Hearn,[66][67] Krefft was one of the very few Australian scientists in the 1860s and 1870s who supported Darwin's position on the origin of species by means of natural selection.

[68][69][70] Alvar Ellegård's extensive (1958) survey of the coverage of the "Darwinian doctrine" in the U.K. press between 1859 and 1872[74] distinguished three aspects — "first, the Evolution idea in its general application to the whole of the organic world; second, the Natural Selection theory; and third, [the] theory of Man's descent from the lower animals" (Ellegård, 1990, p. 24) — and identified five ideological "positions" taken (or ideological "attitudes" displayed) by individual participants over that decade and a half,[75] which were determined, to a considerable extent, not only by their levels of education,[76] but also by their particular politico-social,[77] philosophical,[78] and/or religious orientation.

Setting aside disciplinary "outliers" such as FitzGerald, Hearn, and Krefft (each of whom held position (E)) — and ignoring the (peripheral) fact that Charles Darwin was elected as an honorary member of the Royal Society of New South Wales in 1879,[85] and that pro-Darwinians, the natural historian, Thomas Huxley, and the botanist, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, were awarded the Society's prestigious Clarke Medal in 1880[86] and 1885[87] respectively — it was not really until the late 1890s, due to the influence of the academic appointments of William Aitcheson Haswell to the University of Sydney, Baldwin Spencer to the University of Melbourne, Ralph Tate to the University of Adelaide, and James Thomas Wilson to the University of Sydney, etc.,[88] and the administrative/curatorial appointments of Robert Etheridge to the Australian Museum in Sydney, Baldwin Spencer to the National Museum of Victoria in Melbourne, and Herbert Scott to the Queen Victoria Museum in Launceston, etc., that the majority of Australian scientists began to move away from (A) or (B), and that "the contributions of Darwin and his successors [could begin to] seriously affect Australian thinking and bring it into the mainstream of scientific thought" (Mozley, p. 430).

In order to avoid the military draft, Krefft moved to New York City in 1850,[90][91] where he was employed as a clerk and a draughtsman, and was mainly concerned with producing depictions of sea views and shipping.

[122] There were also well-founded accusations that, "[having arrived] in Adelaide in August 1857 with twenty-eight boxes containing 17,400 specimens",[122] Blandowski had failed to deliver the material collected during his expedition upon his return to Melbourne, despite being "ordered three times by the Victorian government to return his specimens and manuscripts"[122] — a fact that explains, in the absence of any coherent account in English of Blandowski's collected material, the value of Krefft's later accounts (1865a and 1865b) of the expedition's discoveries.

When "threatened by legal action by the Victorian government over the ownership of the Expedition notebooks and illustrations" (Menkhorst, 2009, p. 85), Blandowski hurriedly (and secretly) left Melbourne, on 17 March 1859 (on Captain A.A. Ballaseyers's Prussian barque Mathilde), never to return.

He was also responsible for arranging and cataloguing the Museum's collection of donated fossils, as well as those he had discovered during his own exploratory efforts in the field,[142][143] such as the two important excavations of the fossil remains of megafauna (mammals, birds, and reptiles) he conducted in 1866 (in the company of his assistants Henry Barnes and Charles Tost) and 1869 (in the company of his assistant Henry Barnes, along with William Branwhite Clarke, the Museum trustee, and Edward Deas Thomson, the Chancellor of the University of Sydney)[144] at the Wellington Caves.

[184] Many of those annual reports also contain specific, urgent appeals for additional funding to allow the publication of various items, created by Krefft, that were, at the time, complete and printer-ready.

An extended, critical editorial in The Empire in 1868 noted that, although Krefft had a "voluminous catalogue of the specimens contained in the library arranged for the printer" it appeared that "there are no funds to enable the trustees to carry out this necessary matter".

These pictures are coloured by a process invented by Mr. Krefft, which appears to be entirely different from any method in ordinary use, producing an effect remarkable for its delicacy of tone, though adhering strictly to fidelity to nature, and preserving intact the most minute details of the original photograph.

16, 57, 68), given the London's scientific elite's widespread prevailing mistrust of the observations and material evidence of the colonial explorers and naturalists,[193] Krefft's images not only provided "incontrovertible photographic evidence" of his claims for a specific item of interest, but also — given the extremely wide range of disciplinary mindsets prevailing at the time — served as (inclusive) "boundary objects": viz., entities that "facilitate[d] an ecological approach to knowledge making and sharing" by "provid[ing] connections between different individuals and groups who nevertheless might view them, interpret them, and use them in distinct ways, or for different aims" (p. 10).

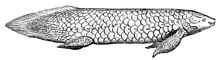

[194] In 1835, having examined teeth that had been extracted from the Rhaetian (latest stage of the Triassic) fossil beds of the Aust Cliff region of Gloucestershire in South West England, the Swiss natural historian Louis Agassiz had identified and described ten different species of a holotype (or "type specimen"), which he named ceratodus latissimus ('horned tooth' + 'broadest'),[196] and had supposed — based upon the structure of their teeth plates resembling that of a Port Jackson shark[197][198] — that they were a kind of shark or ray, and from this, he had postulated, belonged to an order of the class of cartilaginous fishes (Chondrichthyes) collectively known as Chimaera.

From his detailed (and, perhaps, unique to Australia) familiarity with the relevant scientific literature, and from the specimen's unusual teeth, Krefft immediately "understood its enormous significance",[204] and recognized it as being something that "was halfway between dead (fossilised, like its nearest relatives) and alive (known to science)[205] — and, thus, "a living example of [Agassiz's] Ceratodus, a creature, thought to have been like a shark, which had hitherto been known only from fossil teeth":[206] a parallel to the (1994) recognition of the true identity of the Wollemi pine as a "living fossil".

[212]Krefft immediately announced his discovery in a letter to the Editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, published on 18 January 1870 (1870a); and, in doing so, he also named the specimen after William Foster: Ceratodus Forsteri.

With an enterprise anticipating that of the modern information scientist, Krefft recognized the economic, social, and educational value of a wider dissemination of an accurate, up-to-date knowledge and understanding of scientific matters (especially Australian natural history) to the emerging colony and its developing community, as well as "teach[ing] the interested public more about Australia's environments and animals" (Finney, 2023, p. 35).

In the absence of funding for potential museum publications, and in pursuit of a wider dissemination of these scientific matters, it is significant that from March 1871 until June 1874 Krefft contributed more than one hundred and fifty lengthy articles in the "Natural History" section of the The Sydney Mail — a widely-read weekly magazine published every Saturday by The Sydney Morning Herald — on an extremely wide range of relevant subjects, specifically directed at an educated Australian lay audience; rather than, that is, engaging with his well-informed fellow scientists.

Moreover, he wrote, because "the most useful books" were little known, and given that many of those were "so expensive that they cannot be purchased, except by the wealthy", he proposed to present a series of articles on Australian natural history, with the hope that their aggregate would eventually be published as a complete work.

[232][233] Krefft wrote of the "dreadful [overall] ... ignorance of even well educated people", and the constant criticisms of Darwin's "theories" that were still being voiced in Melbourne, 13 years after the publication of Origins, by the devout Irish Roman Catholic Professor Frederick McCoy, Professor of Natural Science at the University of Melbourne, and the director of the National Museum of Victoria, and the Evangelical Anglican Bishop of Melbourne Charles Perry, as well as the recent (7 July 1873) well-attended "Noah's Ark" lectures,[58] that had been delivered in Sydney by the Melbourne-based Irish Jesuit, Joseph O'Malley, and chaired by the devout Irish Roman Catholic layman, Justice Peter Faucett of the Supreme Court of New South Wales.

[231] In his quest to encourage people to read Darwin's works, and to present a summary of the relevant scientific advances in the field (as represented in the professional literature), Krefft published two important "Natural History" articles in July 1873[235] — and, as was his habit,[236] Krefft took the position of presenting the latest views and opinions of others (for the edification of his readers), rather than expressing his own: The first article, centred upon an objective discussion of the current developments in the scientific understanding of artificial selection and human evolution (contrasted with the supposed 'immutability of species'), only expressing Krefft's personal views towards the end of the article, when speaking of the "poor, ignorant, and superstitious" people, whose artistic representations of angels were "decidedly against the laws of nature".

Following his return to the Museum on Christmas Eve 1873, Krefft reported to the trustees (who were individually and collectively unaware that any theft had taken place) that he had discovered a robbery of "specimens of gold to the value of £70".

[271][272][273][274] Krefft had been suspended following an investigation by a subcommittee of trustees — Christopher Rolleston, Auditor-General of New South Wales, was appointed chairman, and Archibald Liversidge, Professor of Geology and Mineralogy at the University of Sydney, Edward Smith Hill, wine and spirit merchant, and Haynes Gibbes Alleyne, of the New South Wales Medical Board — who, having examined a number of witnesses, found some of the charges against Krefft sustained, and also claim to have discovered "a number of [other] grave irregularities".

In November 1874 Krefft brought an action to recover £2,000 damages for trespass and assault against the trustee, Edward Smith Hill, who was physically present at, and had directed his eviction.

[304] Justice Hargrave, noting that the trustees' behaviour was "altogether illegal, harsh, and unjust", and that they had acted "without affording [Krefft] the slightest means of vindicating himself personally, or his scientific or official character as Curator of our Museum"[305] was of the opinion that a new trial should be refused.

He died in Sydney, on 18 February 1881, at the age of 51,[322][323] from congestion of the lungs, "after suffering for some months past from dropsy and Bright's disease",[324] and was buried in the churchyard of St Jude's Church of England, Randwick.

Bishop of Natal (1875).

by Gerard Krefft (1857). [ 89 ]

by Gerard Krefft (1857).

Sydney Mail , 5 July 1873. [ 234 ]

23 December 1873 robbery. [ 254 ]

23 December 1873 robbery. [ 255 ]

23 December 1873 robbery. [ 256 ]

by Gerard Krefft (1857).