German radio intelligence operations during World War II

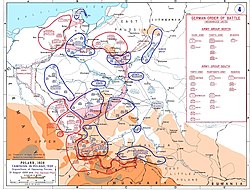

The German Army organisation for mobile warfare was still incomplete; results were jeopardized at first by the great distances between intercept stations and the target areas, and later by defective signal communication which delayed the work of evaluation.

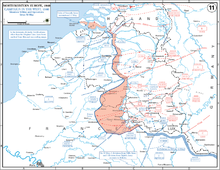

[20] Prior to the start of major operation the information obtained by radio intelligence from the northern sector held by the British and French forces was not particularly valuable because of the great distance involved, for instance 210 miles between Lille and Münster, and because of its largely technical character.

[20] Unusually long encrypted messages, likewise unbreakable, from the French First Army headquarters to an unidentified senior staff located south of the Somme suggested that joint action for attempting breakouts was being agreed on by radio.

[20] On 5 June, when Army Group B crossed the River Somme, radio messages were intercepted which indicated that the enemy was concerned about the impending German attack because insufficient progress had been made in completing the positions between Fismes and Moselle.

In the beginning, the training exercises in these areas were still characterized by the same excellent radio discipline which was observed by the fixed nets, such as rapid tuning of transmitters preparatory to operation, brevity, and speed of transmission, and avoidance of requests for repeat.

It enabled the Germans, for example, to follow every detail of an engagement during maneuvers, including the identification of tactical objectives as provided by British reconnaissance planes, the operations of major formations, and reports sent upon completion of a bombing mission, all from the interception of plaintext messages.

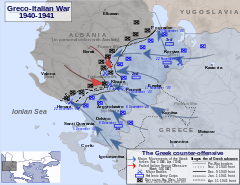

These mistakes included These types of mistakes were possibly part of a deception scheme run by the Advanced Headquarters 'A' Force unit, or sloppy radio procedures used before the retraining undertaken by the British Eighth Army under the command of Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery in early-mid 1942 (North African Campaign#Western Desert Campaign); The information which the intercept company of the Africa Corps gathered was mainly of the short-range type, supplemented by long-range intelligence carried out by the Office of the Commander of Communication Intelligence, of which there were four in the Balkans, who operated against British forces in the Near East.

On repeated occasions radio intelligence was able to observe that the British were taken in by this stratagem, and that apparently without any confirmation by their reconnaissance planes, they sent tanks and motorized artillery, once even an armoured division, to oppose the fictitious Axis allies.

"[26] One interesting observation by this company was the interception of appeals for assistance and water sent by radio to the British Eighth Army by the German Communist Battalion commanded by Ludwig Renn in the desert fort of Bir Hakeim, south of Tobruk.

Other sections of this study describe how German communication intelligence was for the most part capable of overcoming even these difficulties after a period of experimentation, during which results diminished, and how in the heat of combat or when opposed by less disciplined units, the Allies repeated the same mistakes over and over again.

[28] Some trivial details furnished information to communication intelligence, as is shown by the following examples: An impending attack against German defenses in the Naples area, was detected in time because a small supply unit mentioned that rum was to be issued on a certain day.

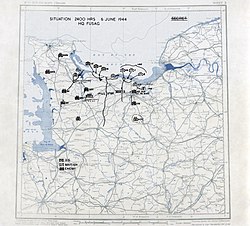

A subsequent comprehensive evaluation prepared sometime after the start of the Allied invasion showed that approximately ninety-five per cent of the units which landed in Normandy had been previously identified in the British Isles by means of intensive radio intelligence.

Locator cards, regularly issued by the communication intelligence control centre, contained precise information about newly organised divisions, and the appearance or disappearance of radio traffic from and to specific troop units.

Any different action would have been a grave blunder, not to be expected of an enemy who had had five years of varied wartime experience, both good and bad, with German communication intelligence and who after a long period of preparation was now launching the decisive battle of the war.

[29] The postwar press gave much attention to the opinion expressed by General Alfred Jodl, the Chief of the Armed Forces Operations Staff, who said that a second landing was expected north of the Seine and that therefore the German reserves and the Fifteenth Army stationed in that area were not immediately committed in a counterattack.

Their contention was that the Russians used better methods to render their traffic secure, sent fewer messages in plaintext, maintained radio discipline, and posed a greater problem to German direction finder units than their Western Allies.

[30] As a result of the new intercept operations, which had been initiated from the west bank of the Dnieper, the impression soon arose that the enemy radio traffic was becoming steadier, a symptom which obviously pointed to a reorganisation, and presumably to a stiffening of Soviet resistance.

After the Germans had occupied the peninsula with the exception of Sevastopol, which was no longer of interest from a long-range intelligence point of view, the 7th Intercept Company was moved north in early June 1942 in order to increase the coverage or the Kharkov area.

Abandoning its long and medium wave direction-finding operations for the time being, the company was employed for intercept purposes only, after experiments had shown that reception of short-wave signals from the Kuban and Caucasus areas was more favourable, or at least of equal quality, at a greater distance from the objective.

[30] During August, the solution of a large number of the Soviet cryptographic systems enabled the Germans to plot the disposition of the Russian divisions defending the east bank of the Don between the mouth of the Khopyor River and Voronezh.

The vastness of European Russia, the indescribably difficult terrain conditions, especially after the beginning of the muddy season (Rasputitsa), and finally the unusually low temperatures, which occasionally halted the work of the D/F teams, interfered with the efficiency of operations.

[30] This deviation from strict adherence to regulations was one of the most vulnerable points in the Soviet radio service, and provided German long-range intelligence with reliable information along the entire front, even after the above-mentioned changes in procedure.

In many instances the Germans were able to learn of plans which the higher echelon headquarters was extremely careful to keep secret by intercepting messages from such units as formations of the assault specialist, Sokolovski, and the heavy mortar, rocket launcher, and army engineer forces.

[30] In some instances, German intercept units were able to follow movements by rail of newly organised divisions from the interior of the Soviet Union up to the front, first by plotting their location through D/F procedures, then by picking up their trail as soon as they established contact with the headquarters to which they were assigned.

Radio intelligence furnished the usual profusion of details about division boundaries, the location and stock level of ammunition dumps, and the exact coordinates of tank-supporting bridges, lanes through minefields, and field emplacements.

On the other hand, one must acknowledge that until the very day of the German capitulation, the Russians never indulged in the complete relaxation of all rules and undisciplined plain-text transmission of radio messages which was practiced by the Western Allies in anticipation of an early victory.

In the autumn of 1943 Albert Praun, then chief signal officer at the headquarters of Army Group Centre, received every day intercepts of CW and voice transmissions from which it was clearly evident that in hundreds of instances German prisoners were being murdered within a short time after their capture.

In this area the Germans were still able to supplement the results of communication intelligence by air reconnaissance, which provided information on the arrival of motorized and tank units as well as data on the assembly of artillery forces which moved up during the hours or darkness.

When the storm finally broke on 12 January 1945, the defense forces in the front lines, their superior headquarters, and the Chief of the Army General Staff were not surprised by the fury of the assault, the Russian points of main effort, or the directions or their attacks.

Once the first overt act of war had been committed and a certain period of initial adjustment was over, German communication intelligence was able to furnish the military leadership with a wealth of reliable information which was appreciated by the General Staff and senior commanders in the field.

|

Initial Nationalist zone – Jul 1936

Nationalist advance to Sep 1936

Nationalist advance to Oct 1937

Nationalist advance to Nov 1938

Nationalist advance to Feb 1939

Last area under Republican control

|

|