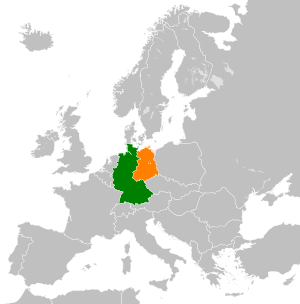

German reunification

The East German government, controlled by the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), started to falter on 2 May 1989, when the removal of Hungary's border fence with Austria opened a hole in the Iron Curtain.

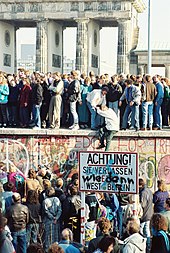

In 1987, the United States President Ronald Reagan gave a famous speech at the Brandenburg Gate, challenging Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev to "tear down this wall" which prevented freedom of movement in Berlin.

The opening of a border gate between Austria and Hungary at the Pan-European Picnic on 19 August 1989 then set in motion a peaceful chain reaction, at the end of which there was no longer a GDR and the Eastern Bloc had disintegrated.

After the picnic, which was based on an idea of Karl's father Otto von Habsburg to test the reaction of the USSR and Mikhail Gorbachev to an opening of the border, tens of thousands of media-informed East Germans set off for Hungary.

[33] But, with the mass exodus at the Pan-European Picnic, the subsequent hesitant behavior of the Socialist Unity Party of East Germany and the nonintervention of the Soviet Union broke the dams.

[58] Vacant lots, open areas, and empty fields in East Berlin were subject to redevelopment, in addition to space previously occupied by the Wall and associated buffer zone.

[61] Heinrich August Winkler observes that "an evaluation of the corresponding data in the Deutschland Archiv in 1989 showed that the GDR was perceived by a large portion of the younger generation as a foreign nation with a different social order which was no longer a part of Germany".

[63] He observes that "right-wing violence was on the rise throughout 1990 in the GDR, with frequent instances of beatings, rapes, and fights connected with xenophobia", which led to a police lockdown in Leipzig on the night of reunification.

Christa Wolf and Manfred Stolpe stressed the need to forge an East German identity, while "citizens' initiatives, church groups, and intellectuals of the first hour began issuing dire warnings about a possible Anschluss of the GDR by the Federal Republic".

[63] David Gress remarked that there was "an influential view found largely, but by no means only, on the German and international left" which saw "the drive for unification as either sinister, masking a revival of aggressive nationalist aspirations, or materialist".

[71] Günter Grass, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1999, also expressed his vehement opposition to the unification of Germany, citing his tragic memories of World War II as the reason.

"[63] British historian Richard J. Evans made a similar argument, criticizing the unification as driven solely by "consumerist appetites whetted by years of watching West German television advertisements".

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, who speculated that a country that "decided to kill millions of Jewish people" in the Holocaust "will try to do it again", was one of the few world leaders to publicly oppose it.

Although some top American officials opposed quick unification, Secretary of State James A. Baker and President George H. W. Bush provided strong and decisive support to Kohl's proposals.

Before the fall of the Berlin Wall, Thatcher told Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev that neither the United Kingdom nor, according to her, Western Europe, wanted the reunification of Germany.

[84] A representative of French President François Mitterrand reportedly told an aide to Gorbachev, "France by no means wants German reunification, although it realises that in the end, it is inevitable.

[73] Mitterrand recognized before Thatcher that reunification was inevitable and adjusted his views accordingly; unlike her, he was hopeful that participation in a single currency and other European institutions could control a united Germany.

This belief, and the worry that his rival Genscher might act first, encouraged Kohl on 28 November to announce a detailed "Ten Point Program for Overcoming the Division of Germany and Europe".

[73][90] The Americans did not share the Europeans' and Soviets' historical fears over German expansionism; Condoleezza Rice later recalled,[91] The United States—and President George H. W. Bush—recognized that Germany went through a long democratic transition.

This was followed by the closure of the United States Army Berlin command on 12 July 1994, an event that was marked by a casing of the colors ceremony witnessed by President Bill Clinton.

[94] Although the bulk of the British, American, and French Forces had left Germany even before the departure of the Russians, the Western Allies kept a presence in Berlin until the completion of the Russian withdrawal, and the ceremony marking the departure of the remaining Forces of the Western Allies was the last to take place: on 8 September 1994,[95] a Farewell Ceremony in the courtyard of the Charlottenburg Palace, with the presence of British Prime Minister John Major, American Secretary of State Warren Christopher, French President François Mitterrand, and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, marked the withdrawal of the British, American and French Occupation Forces from Berlin, and the termination of the Allied occupation in Germany.

[107][108] A public manifestation of coming to terms with the past (Vergangenheitsbewältigung) is the existence of the so-called Birthler-Behörde, the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records, which collects and maintains the files of the East German security apparatus.

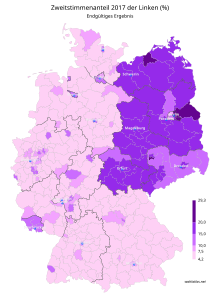

[109] The economic reconstruction of former East Germany following the reunification required large amounts of public funding which turned some areas into boom regions, although overall unemployment remains higher than in the former West.

[118] Despite development of sites for commercial purposes, Berlin struggled to compete in economic terms with Frankfurt which remained the financial capital of the country, as well as with other key West German centers such as Munich, Hamburg, Stuttgart and Düsseldorf.

[119][120] The intensive building activity directed by planning policy resulted in the over-expansion of office space, "with a high level of vacancies in spite of the move of most administrations and government agencies from Bonn".

[118] At the close of the century, it became evident that despite significant investment and planning, Berlin was unlikely to retake "its seat between the European Global Cities of London and Paris", primarily due to the fact that Germany's financial and commercial capital is located elsewhere (Frankfurt) than the administrative one (Berlin), in resemblance of Italy (Milan vs Rome), Switzerland (Zürich vs Bern), Canada (Toronto vs Ottawa), Australia (Sydney vs Canberra), the US (New York City vs Washington, DC) or the Netherlands (Amsterdam vs The Hague), as opposed to London, Paris, Madrid, Vienna, Warsaw or Moscow which combine both roles.

Those who lived in West Germany and had social ties to the East experienced a six percent average increase in their wealth in the six years following the fall of the Wall, which more than doubled that of households who did not possess the same connections.

Labour reforms implemented after the unification focused on reducing costs for companies and dismantled East German wage and social security regulations in favour of incentivizing employers to create jobs.

North and South Korea as well as Mainland China and Taiwan still struggle with high political tensions and huge economic and social disparities, making a possible reunification an enormous challenge.

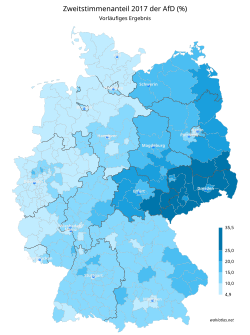

East and West Germany today also still have differences in economy and social ideology, similar to North and South Vietnam, a legacy of the separation that the German government is trying to equalize.