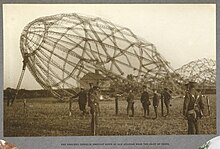

German bombing of Britain, 1914–1918

Until the Armistice the Marine-Fliegerabteilung (Navy Aviation Department) and Die Fliegertruppen des deutschen Kaiserreiches (Imperial German Flying Corps) mounted over fifty bombing raids.

Concern about the conduct of the defence against the raids, the responsibility for which was divided between the Admiralty and the War Office, led to a parliamentary inquiry under Jan Smuts and the creation of the Royal Air Force (RAF) on 1 April 1918.

664) of 7 Squadron Royal Flying Corps (RFC), flown by Second-Lieutenant Montagu Chidson and the gunner, Corporal Martin, overtook the raider near Erith and attacked over Purfleet.

[12] The Vickers machine gun carried by the F.B.4 jammed and Martin resorted to a carbine, loaded with nine rounds of incendiary ammunition, reserved for attacks on airships.

Two Zeppelins were to attack targets near the Humber estuary but were diverted south by strong winds and dropped their bombs on Great Yarmouth, Sheringham, King's Lynn and the surrounding Norfolk villages.

[26] Aware of the difficulties that the Germans were experiencing in navigation, the government issued a D notice prohibiting the press from reporting anything about attacks not mentioned in official statements.

[28] On the same night a raid by three Army Zeppelins also failed because of the weather; as the airships returned to Evere they ran into RNAS aircraft flying from Veurne, Belgium.

LZ38 was destroyed on the ground and LZ37 was intercepted in the air by Reginald Warneford in a Morane Parasol, who dropped six 9 kg (20 lb) Hales bombs on the Zeppelin, setting it on fire.

[29] After an ineffective attack by L10 on Tyneside on 15/16 June the short summer nights discouraged further raids for some months and the remaining Army Zeppelins were reassigned to the Eastern and Balkan fronts.

More bombs were dropped on Holborn, as the airship neared Moorgate it was engaged by a new French 75 mm anti-gun mounted on a lorry and manned by naval ratings from disbanded armoured car squadrons sited at the Honourable Artillery Company grounds in Finsbury.

Poor weather, difficulty in navigating and mechanical problems scattered the aircraft across the Black Country, bombing Tipton, Wednesbury and Walsall; 61 people were reported killed and 101 injured.

[48] Loewe appealed for rescue but the trawler skipper refused, despite offers of money, fearful of his crew of eight being overpowered by the Germans; a search was conducted but nothing was found.

A B.E.2c piloted by 2nd Lieutenant Wulstan Tempest engaged the Zeppelin at around 11:50 p.m.; three bursts were sufficient to set fire to L31 and it crashed near Potters Bar with all 19 crew killed, Mathy jumping to his death.

[65] L21 was shot down by three aircraft near Yarmouth; Flt Sub-Lieutenant Edward Pulling was credited with the victory and awarded a DSO, the other pilots receiving the DFC.

[66] The following day a LVG CIV made the first German aeroplane raid on London; hoping to hit the Admiralty, six 22 lb (10 kg) bombs were dropped between Victoria station and the Brompton Road.

[70] Kagohl 3 was based temporarily at Ghistelles, which was too close to the Western Front and British aircraft, before moving 40 mi (64 km) back into German-occupied Belgium.

On the return flight, L39 (army name LZ86 Type R), commanded by Kapitänleutnant Koch, suffered an engine failure, was blown over French-held territory and brought down in flames near Compiègne by ground fire.

On taking off for the return journey, his aircraft had an engine failure; Brandenburg was severely injured and his pilot, Oberleutnant Freiherr von Trotha, was killed.

[84][f] On the night of 16/17 June, an attempted raid by six Zeppelins met with some success; two airships were unable to leave their shed due to high winds and two more turned back with engine problems.

Of the two that reached England, L42 hit a naval ammunition store in Ramsgate, while L48, the first U-class Zeppelin, was intercepted near Harwich and attacked by a DH.2 flown by Captain Robert Saundby, a F.E.

The G V and later Gotha models, even the G VII, built to reach an altitude of 20,000–23,000 ft (6,000–7,000 m), were never delivered in sufficient numbers to make a return to day bombing feasible.

The commander of the Western sub-section of the London Air Defence Area, Lt-Col. Alfred Rawlinson (holder of Royal Aero Club Aviator's Licence No.

3 and brother of Sir Henry Rawlinson), surmised that the airships were likely to switch off their engines; carried silently on the wind over central London, they would drop their bombs undetected.

[103] The RNAS and RFC carried out bombing raids on German bomber airfields at St Denis-Westrem and Gontrode, forcing the squadrons to relocate to Mariakerke and Oostakker, with the staff headquarters moving to Ghent.

Six of the Gothas turned back before reaching England and the rest made landfall at about 8:00 p.m. Over a hundred British night-fighter sorties were flown, resulting in one Gotha being shot down after being subjected to a co-ordinated attack by two Camels from 40 Squadron RFC, flown by Second Lieutenants Charles (Sandy) Banks and George Hackwill, the first victory for night-fighters against a heavier-than-air bomber over Britain; both pilots were awarded the DFC.

[114] Rfa 501 attacked again on the night of 16/17 February, four aircraft reached England, one carrying a 2,200 lb (1,000 kg) bomb which, aimed at Victoria station, fell half a mile away on the Royal Hospital, Chelsea.

[116] Another Giant raid took place on 7 March; five aircraft reached England, one carrying a 2,200 lb (1,000 kg) bomb, which fell on Warrington Crescent near Paddington station.

[123] Thousands of Elektron bombs were delivered to bomber bases and the operation was scheduled for August and again in early September 1918 but on both occasions, the order to take off was countermanded at the last moment, perhaps because of the fear of Allied reprisals, Germany being on the brink of surrender.

The airships reached the British coast before dark and were sighted by the Leman Tail lightship 30 mi (48 km) north-east of Happisburgh at 8:10 p.m., although defending aircraft were not alerted until 8:50 p.m.

An attempt was made to salvage the wreckage of L 70 and most of the structure was brought ashore, providing the British a great deal of technical information; the bodies of the crew were buried at sea.