German militarism

During the first half of the 20th century, German militarism reached its peak with two World Wars, which were followed by a consistent anti-militarism and pacifism within Germany since 1945, with a strong non-conformist tendency within subsequent generations.

The roots of German militarism in the traditional understanding can be found in Prussia in the 18th and 19th centuries, with the Unification of Germany under Prussian leadership serving as an important event.

German nobel laureate Elias Canetti summarised the influence of militarism in Germany after the Franco-Prussian War as following: "Peasants, the bourgeois, workers, Catholics, Protestants, Bavarians, Prussians - they all saw the army as the symbol of the nation.

Another factor in the lacking performance of the Prussian army can be found in the fact that a large share of the command was held by non-Prussian officers, who, as mercenaries, did not have much connection to the land of Prussia.

French soldiers, due to their higher willingness to serve in arms, were capable of far more flexible tactics and maneuvres outside of the static line formation.

After Napoleon Bonaparte conquered Prussia during the War of the Fourth Coalition in 1806, he enforced the reduction of the Prussian army to 42,000 men in the Peace of Tilsit.

In the following decades up to 1914, patriotism as had been expressed in 1848 turned into a radical and militant nationalism, with enablers and sympathisers existing across all classes, which increasingly also led to an acceptance of racist and discriminatory strains of thought in a grander sense of German superiority.

In an opposing model, for instance in France and the United Kingdom, democratic institutions such as parliament became the main identifying factor of the population with the state and nation.

[14] The industrial production of armaments, the continuous growth of the population and the resulting larger number of conscripts, new technologies as well as the ever-increasing penetration of the military into civilian life led to a paradigm shift.

[16] After Bismarck was dismissed, a psychotic-masculine false perception of reality dominated both politics, the economy and civilian society, reflected within foreign and social policy.

Both streams of militarism, a feudal conservative and civic nationalist one, increasingly wrung over influence over the army and politics, with the latter gaining dominance in both internal as well as external matters.

[18] A large expansion of the German fleet as well as steadily growing land forces increased the number of citizens in uniform in Germany.

That opposition remained in the minority, however, when the signs of global politics pointed towards the outbreak of war in the summer of 1914 and a new German bourgeoisie spread aggressively chauvinistic viewpoints relating to imperialism and world conquest.

This was further worsened by the development of theories by militant geographers and economists, who introduced the concept of Lebensraum, but also by the philosophy of Nietzsche with the strong-willed Herrenmensch serving as an ideal.

[27] It had led the German people to believe that their nation was encircled by enemies – the Triple Entente of France, Russia and Great Britain – and that they were engaging in a purely defensive war.

A key figure in the contemporary intellectual movement can be found in the person of Werner Sombart, who wrote the treatise Merchants and Heroes in 1915, praising the primacy of all military interests in the country.

The historian and journalist Henry Wickham Steed formulated a program of "Changing Germany", with militarism being assumed as the foundation of German culture.

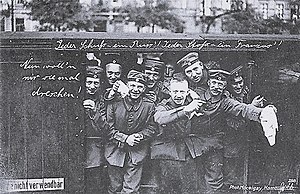

An army of men now disconnected from civilian life, emotionally insensitive and trained on fighting on the front, returned home and witnessed a devastating process of change in all aspects of society.

In an act of desperation to keep their political influence even after the war had ended, the OHL spread the Stab in the Back myth from October 1918 onwards, leading to a broad revanchism in the German population.

[41] The societal militarism of the 1920s was proven to exist by the politician Ludwig Quidde and the pedagogue Friedrich Wilhelm Foerster as well as the historian Franz Carl Endres and Eckart Kehr with their works about armament, elites and mentalities.

The reintroduction of conscription on 21 May 1935 was only the latest episode after the establishment of several paramilitary state-led organisations such as the Hitler Youth, the Reichsarbeitsdienst, the SA, the Schutzstaffel (SS), and others.

After Germany's defeat in 1945, the Allies systematically attempted to reeducate the entire German people as a cultural counter to the persistent militarism of the country.

Characterisations of German militarism in English-speaking literature described several real and alleged aspects of German culture that supposedly led to this form of militarism, among which were "Kadavergehorsam" (unrelenting and unquestioning submission to authority, even with the potential to severely harm oneself), a spirit of self-subjection, conformism, the Pickelhaube, sadistic Junker with scars covering their face, but which also included more general terms such as aggression, the will to expand and racism.

[48] The catastrophe of World War II led to militarism becoming widely discredited in Germany, as the second grand defeat in two decades had befallen the country.

In the early years of the Federal Republic, the militaristic tendencies of German society from before the war still lingered, however with decreasing intensity as a new generation grew up, raised more within the world-view of a liberal democracy.

It became a social taboo to talk about one's own events relating to the Nazi era and the militarism association with it, being combined with the fact that several old elites managed to get back into positions of power in the early Federal Republic.

East German social scientists analysed the connections between the military-industrial complex (an alliance between party, military, economy and bureaucracy) from 1871 to 1945 as well as personal continuities within the West Germany.

[60] Through the partial adoption of visual and mental elements from the Prussian state, dissolved in 1947, the GDR was occasionally labelled as "Red Prussia" in West German media.

The real threat of a confrontation with the Western alliance was channeled through indoctrination and propaganda, in order to mobilise the population through the projection of an enemy image.

Those foreign missions have become increasingly accepted by the general population, despite great initial reservations, a development that can similarly be observed in Japan, another loser of World War II.