Germanic heroic legend

The most widely and commonly attested legends are those concerning Dietrich von Bern (Theodoric the Great), the adventures and death of the hero Siegfried/Sigurd, and the Huns' destruction of the Burgundian kingdom under king Gundahar.

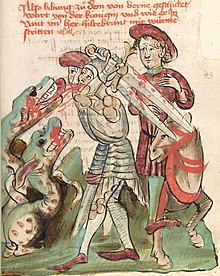

"[13] The hero is typically a man, sometimes a woman, who is admired for his or her achievements in battle and heroic virtues, capable of performing feats impossible for a normal human, and who often dies tragically.

[42] As an example of the variability of the tradition, Edward Haymes and Susan Samples note that Sigurd/Siegfried is variously said to be killed in the woods or in his bed, but always with the fixed detail that it was by a spear in the back.

[59] The creation of several heroic epics also seems to have been prompted by ecclesiastics, such as Waltharius, possibly Beowulf,[60] and the Nibelungenlied, which was probably written through the patronage of bishop Wolfger von Erla of Passau.

The picture stone Smiss I from Gotland, dated around 700, appears to depict a version of the legend of Hildr: a woman stands between two groups of warriors, one of which is arriving on a ship, and seems to seek to mediate between the two sides.

This corresponds to a version of the legend known from 12th-century Germany, in which Hildr (Middle High German: Hilde) seeks - ultimately unsuccessfully - to mediate between her father, Hagene, and the man who seized her for marriage, Hetel.

[65] The Gotland Image stone Ardre VIII, which has been dated to the 8th c.,[66] shows two decapitated bodies, a smithy, a woman, and a winged creature which is interpreted as Wayland flying away from his captivity.

The church portal of San Zeno Maggiore in Verona (c. 1140) appears to depict a legend according to which Dietrich rode to Hell on an infernal horse, a story contained in the Þiðreks saga and alluded to elsewhere.

The decorations include depictions of triads of figures, among them the heroes Dietrich, Siegfried, and Dietleib von Steiermark, as well as three giants and three giantesses labeled with names from heroic epics.

The 7th-century Pforzen buckle, discovered in 1992 in an Alemannic warrior's grave in southern Germany, has a short runic inscription that may refer to Egil and Ölrun, two figures from the legend of Wayland the smith.

[110][111] The legend of Walter of Aquitaine is told in the fragmentary Waldere, which also includes mentions of the fights of the heroes Ðeodric (Dietrich von Bern) and Widia (Witege), son of Wayland, against giants.

[119] Some of the oldest written Scandinavian sources relate to the same heroic matter as found in Beowulf, namely Langfeðgatal (12th c.), the Lejre Chronicle (late 12th c.), Short History of the Kings of Denmark (c. 1188), and the Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus (c.

[149] Werner Hoffmann defined five subjects of heroic epics in medieval Germany: the Nibelungen (Burgundians and Siegfried), the lovers Walther and Hildegund, the maiden Kudrun, kings Ortnit and Wolfdietrich, and Dietrich von Bern.

[163] Evidence for the continued existence of heroic legends in what is now Northern Germany and the Low Countries is provided by the Þiðreks saga on the one hand,[164] and the early modern ballad Ermenrichs Tod (printed 1560 in Lübeck) on the other.

[180] Klaus von See gives the following examples from Old English, Old High German, and Old Norse (stressed syllable underlined, alliteration bolded, and || representing the caesura):[181] Oft Scyld Scēfing || scēaþena þrēatum (Beowulf v. 4)forn her ostar giweit || floh her Ōtachres nīd (Hildebrandslied v. 18)Vilcat ec reiði || rícs þióðkonungs (Grípisspá v. 26)The poetic forms diverge among the different languages from the 9th century onward.

West Germanic heroic poetry tends to use what Andreas Heusler called Bogenstil ("bow style"): sentences are spread across various lines and often begin at the caesura.

By the late 9th century, a figure known in Old English as a scop, in Old High German as a skof, and in Latin texts as a vates or psalmista is attested as a type of singer or minstrel resident at the court of a particular lord.

[216] The Gök runestone (c. 1010- c. 1050[217]) has been said to be a case in point of how the older heroic poetry dissolved in Sweden, as it uses the same imagery as the Ramsund carving, but a Christian cross has been added and the images are combined in a way that completely distorts the internal logic of events.

The most influential work from this time may have been the Thomas Bartholin's Antiquitatum Danicarum de causis contempta a Danis adhuc gentilibus mortis (1689), with long scenes from sagas where heroes are followed while they smiling meet death and earn well-deserved places with Odin in Valhalla.

[212] It was quickly dubbed the "German Iliad" (deutsche Ilias) by Swiss scholar Johann Jakob Bodmer, who published his own partial adaptation of the second half of the epic.

[231][232] Romantic figures such as Ludwig Tieck, Christian August Vulpius, and Friedrich Heinrich von der Hagen worked on producing adaptations or editions of older heroic materials.

[240] Sir Walter Scott, often considered the originator of the historical novel, often commented that he was inspired by Old Norse sources, and he mainly acquired them from Thomas Bartholin, Olaus Magnus and Torfaeus.

[246] It was admired by people like Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Kaiser Wilhelm II, William Morris and Selma Lagerlöf, and it inspired undergraduate textbooks, statues, paintings, engravings, seafaring anthologies, travel literature, children's books, works of theater, operas and musicals.

[248] Some of its cultural influence can be found in Longfellow's poetry, bridal quest romance, the Victorian view of Norway, national epics inspired by folklore, and in the history of ice skating.

Wagner's opera mixed elements of the Poetic Edda, the Völsunga saga, and the Nibelungenlied, as mediated by the theories, editions, and translations of the brothers Grimm, von der Hagen, Simrock, and other romantics.

[261] In the interwar years, the Nibelungenlied was heavily employed in anti-democratic propaganda following the defeat of Germany and Austria-Hungary: the epic supposedly showed that the German people were more well suited to a heroic, aristocratic form of life than democracy.

[261] During the Second World War, Hermann Göring would explicitly use this aspect of the Nibelungenlied to celebrate the sacrifice of the German army at Stalingrad and compare the Soviets to Etzel's (Attila's) Asiatic Huns.

[265] In a 1941 letter to his son Michael, Tolkien had expressed his resentment at "that ruddy little ignoramus Adolf Hitler ... Ruining, perverting, misapplying, and making for ever accursed, that noble northern spirit, a supreme contribution to Europe, which I have ever loved, and tried to present in its true light.

[269] To name some of the influence it can be mentioned that in Hrólfs saga kraka, the hero Beowulf corresponds to the shapeshifting (bear-man) Bǫðvarr Bjarki,[270] the latter of whom inspired the character Beorn, in The Hobbit.

The trilogy Wodan's Children (1993-1996), by Diana L. Paxson, narrates the story of the Nibelungen from the perspectives of the female characters, and is one of the few English-language adaptations that is based directly on the medieval sources rather than Wagner's Ring cycle.

Mårten Eskil Winge (1866).

Max Unger (1913)