Germanisation

Under the policies of states such as the Teutonic Order, Austria, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the German Empire, non-German minorities were often discouraged or even prohibited from using their native language,[1] and had their traditions and culture suppressed in the name of linguistic imperialism.

In Nazi Germany, linguistic Germanisation was replaced by a policy of genocide against certain ethnic groups like Poles, Baltic natives, and Czechoslovaks, even when they were already German-speaking.

Early Germanisation went along with the Ostsiedlung during the Middle Ages in Hanoverian Wendland, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lusatia, and other areas, formerly inhabited by Slavic tribes – Polabian Slavs such as Obotrites, Veleti and Sorbs.

As a result, Silesia, Pomerania (in the narrow sense) and Lubusz Land joined the Holy Roman Empire, as a natural consequence becoming gradually Germanised in the following centuries.

When the State of the Teutonic Order unexpectingly seized Polish Pomerelia by force and decimated its population, launching at the same time a massive campaign to attract and ressetle to these areas as many German colonists as possible within a relatively short period.

This event also produced the first historical record of a major German thinker openly calling for the genocide of the Polish people; the 14th-century German Dominican theologian Johannes von Falkenberg argued on behalf of the Teutonic Order not only that Polish pagans should be killed, but that all Poles should be subject to genocide on the grounds that Poles were an inherently heretical race and that even the King of Poland, Jogaila, a Christian convert, ought to be murdered.

[2][3] The assertion that Poles were heretical was largely politically motivated as the Teutonic Order desired to conquer Polish lands despite Christianity having become the dominant religion in Poland centuries prior.

[5] The carnage was so extensive that it prompted the pope Clement V to condemn the Teutonic Knights in a bull which charged them with committing a massacre "Latest news were brought to my attention, that officials and brethren of the aforementioned Teutonic order have hostilely intruded the lands of Our beloved son Wladislaw, duke of Cracow and Sandomierz, and in the town of Gdańsk killed more than ten thousand people with the sword, inflicting death on whining infants in cradles whom even the enemy of faith would have spared.

[citation needed] Following the 1620 Battle of White Mountain, the Lands of the Bohemian Crown, at the time one of the last meaningful territories of the HRE not dominated yet by the German language, was subjected to two centuries of recatholicization of the Czech lands accompanied by growing influence of German-speaking elites, at the expense of declining the Czech-speaking aristocracy, elite Czech language usage in general.

As a further step, Emperor Joseph II (r. 1780–90) sought to consolidate the territories of Habsburg Monarchy within the Holy Roman Empire with those remaining outside of it, to centralise the government, and to implement Enlightenment principles through absolutism.

[10] The Hungarian national revival was so successful that the Government in Budapest did not learn anything from the failure of Emperor Joseph II's linguistic policies and, following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, unwisely launched a coercive Magyarization policy aimed at forcibly assimilating the many speakers of other minority languages within the Kingdom of Hungary, which ultimately triggered a domino effect.

[12][14] After the Napoleonic Wars, Austria remained in possession of parts of Lesser Poland, Galicia, Volhynia, as well as a minor share of Silesia.

Prussia in turn not only retained the bulk of Upper Silesia but upon dissolution of the Duchy of Warsaw it also reclaimed the entire West Prussia (formed by Pomerelia, the northernmost part of Greater Poland and a strip of historical Prussia on the right bank of Vistula) and, most importantly, obtained the bulk of Greater Poland where an autonomous polity was formed under the name of Grand Duchy of Posen with an officially stated purpose to provide its overwhelmingly Polish population a degree of autonomy; in May 1815 King Frederick William III issued a manifest to the Poles in Posen: You also have a Fatherland.

A government that [...] is indifferent or even hostile against them creates bitterness, debases the nation and generates disloyal subjects.Later the first half of the 19th century, Prussian policy towards Poles turned again to discrimination and Germanisation.

Other means of oppression included the Prussian deportations from 1885 to 1890, in which non-Prussian nationals who lived in Prussia, mostly Poles and Jews, were removed; and a ban issued on the building of houses by non-Germans.

[21] Meanwhile, the Austrian-ruled Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria operated two Polish-speaking universities and in 1867 obtained even consent to adopt Polish as its official government language.

[22] Due to migration within the German Empire as many as 350,000 ethnic Poles made their way to the Ruhr area in the late 19th century, where they largely worked in the coal and iron industries.

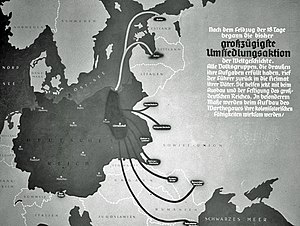

"[30]The Nazis considered land to the east – Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, and the Baltics – to be Lebensraum (living space) and sought to populate it with Germans.

[31] The policy of Germanisation in the Nazi period carried an explicitly ethno-racial rather than purely nationalist meaning, aiming for the spread of a "biologically superior" Aryan race rather than that of the German nation.

Such execution was carried out on the grounds that German blood should not support non-Germanic people,[39] and that killing them would deprive foreign nations of superior leaders.

Gauleiters Albert Forster and Arthur Greiser reported to Hitler that 10 percent of the Polish population contained "Germanic blood", and were thus suitable for Germanisation.

[50] This last group was often given Polish homes where the families had been evicted so quickly that half-eaten meals were on tables and small children had clearly been taken from unmade beds.

[51] Members of the Hitler Youth and the League of German Girls were assigned the task of overseeing such evictions and ensuring that the Poles left behind most of their belongings for the use of the settlers.

The Gestapo arrived on 16 April 1941 and were followed three days later by SS leader Heinrich Himmler, who inspected Stari Pisker Prison in Celje.

Although the Slovenes had been deemed racially salvageable by the Nazis, the mainly Austrian authorities of the Carinthian and Styrian regions commenced a brutal campaign to destroy them as a nation.

[69] When Hitler received a report of many well-fed Ukrainian children, he declared that the promotion of contraception and abortion was urgently needed, and neither medical care nor education was to be provided.

[79] Pamphlets, for instance, enjoined all German women to avoid sexual relations with all foreign workers brought to Germany as a danger to their blood.

However, except for the Prussian and Austrian territories of Poland which lost statehood for a relatively brief period and maintained organised movements resiting vigorously Germanisation attempts, national and linguistic identities among the remaining nationalities barely survived the centuries-long cultural dominance of the Germans; for instance, the first modern grammar of the Czech language by Josef Dobrovský (1753–1829) – Ausführliches Lehrgebäude der böhmischen Sprach (1809) – was published in German because the Czech language was not used in academic scholarship.

The majority of East Elbia affected by the medieval Ostsiedlung ceased being part of German-speaking Europe as a result of loss of the former eastern territories of Germany in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement, with the ensuing re-Polonisation, or in the case of East Prussia, re-Lithuanianisation, Polonisation and Russification of these regions, while the Austrian Germanisation of the Kingdom of Bohemia was reversed by the expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia.

Although German irredentism was fuelled for some time after the war by the Federation of Expellees, ultimately the concept of Germanisation became irrelevant in Germany and Austria upon introduction of Ostpolitik in the 1970s.